Jaskamal Bains

Edward W. Said, the Palestinian American academic and a public intellectual who remained a vocal critic of the Israeli occupation of Palestine all of his life, passed away 18 years ago on this date in New York.

Said remains one of the best known radical voices to have countered the lens of the “otherness” that the West views the Arab Islamic world through, in his 1978 book ‘Orientalism.’

‘Culture and Imperialism’, ‘Covering Islam: How the Media and the Experts Determine How We See the Rest of the World’, ‘The ‘Question of Palestine’ along with ‘Orientalism’ are some of his most influential works.

One of the most prominent intellectuals of the 20th century, Said was also a founder of the discipline of Postcolonial Studies. His critical approach has thus, especially been of great relevance in the field of literary criticism and cultural studies.

Born in Jerusalem in the year 1935, Said moved to Cairo, Egypt in 1947 as the conflict in Palestine began. Further, he moved to the United States, where he spent the rest of his life until his death after enduring twelve years of sickness.

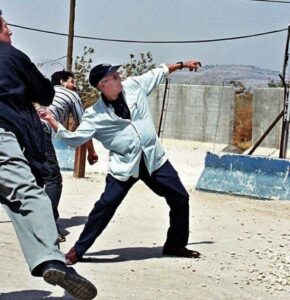

In a widely popular instance, Said was once photographed throwing a stone towards Israeli territory from the Labanese-Israeli border. In the criticism that came after the incident, along with being called out for “inherent and personal sympathy with terrorism,” Said was also labelled as “The Professor of Terror” in a commentary magazine

.

Despite all the repercussions, Said stood as an adamant voice for against the atrocities against the Palestinians. Said’s work and ideas of power, culture, imperialism, exile and homeland continue to shape those of his readers.

As a Palestinian located in America, in the preface of his memoir ‘Out of Place,’ Said writes that the reason behind his writing the memoir was the “need to bridge the sheer distance in time and place between my life today and my life then.”

Said also remembers, in the Preface, how Israeli officials would often ask him when he had left Palestine, to which he would respond by saying that he left in December 1947, accenting the word “Palestine.”

“Do you have any relatives here?” was the next question, to which I answered, “No one,” and this triggered a sensation of such sadness and loss as I had not expected.

Today, on the 18th Death Anniversary of Said, The Kashmiriyat remembers him through the elegy that Mehmoud Darwish (the national poet of Palestine who also lived in exile from the war-torn homeland) wrote in memory of his friend, Edward Wadie Said.

The poem encapsulates the spirit of Said’s works about power, culture, imperialism and the sense of homeland, loss, exile and memories. (Translated to English from Arabic)

New York/ November/ Fifth Avenue

The sun a plate of shredded metal

I asked myself, estranged in the shadow:

Is it Babel or Sodom?

*

There, on the doorstep of an electric abyss,

high as the sky, I met Edward,

thirty years ago,

time was less wild then…

We both said:

If the past is only an experience,

make of the future a meaning and a vision.

Let us go,

Let us go into tomorrow trusting

the candor of imagination and the miracle of grass/

*

*

I don’t recall going together to the cinema

in the evening. Still I heard Ancient

Indians calling: Trust

neither horse, nor modernity

*

No. Victims do not ask their executioner:

Am I you? Had my sword been

bigger than my rose, would you

have asked

if I would have acted like you?

*

A question like that entices the curiosity

of a novelist,

sitting in a glass office, overlooking

lilies in the garden, where

the hand

of a hypothesis is as clear as

the conscience

of a novelist set to settle accounts

with

human instinct… There is no tomorrow

in yesterday, so let us advance/

*

Advancing could be a bridge

leading back

to Barbarism…/

*

New York. Edward wakes up to

a lazy dawn. He plays

Mozart.

Runs round the university’s tennis

court.

Thinks of the journey of ideas across

borders,

and over barriers. He reads the New York Times.

Writes out his furious comments. Curses an Orientalist

guiding the General to the weak point

inside the heart of an Oriental woman. He showers. Chooses

his elegant suit. Drinks

his white coffee. Shouts at the dawn:

Do not loiter.

*

On wind he walks, and in wind

he knows himself. There is no ceiling for the wind,

no home for the wind. Wind is the compass

of the stranger’s North.

He says: I am from there, I am from here,

but I am neither there nor here.

I have two names which meet and part…

I have two languages, but I have long forgotten

which is the language of my dreams.

I have an English language, for writing,

with yielding phrases,

and a language in which Heaven and

Jerusalem converse, with a silver cadence,

but it does not yield to my imagination.

*

What about identity? I asked.

He said: It’s self-defence…

Identity is the child of birth, but

at the end, it’s self-invention, and not

an inheritance of the past. I am multiple…

Within me an ever new exterior. And

I belong to the question of the victim. Were I not

from there, I would have trained my heart

to nurture there deers of metaphor…

So carry your homeland wherever you go, and be

a narcissist if need be/

The outside world is exile,

exile is the world inside.

And what are you between the two?

*

Myself, I do not know

so that I shall not lose it. I am what I am.

I am my other, a duality

gaining resonance in between speech and gesture.

Were I to write poetry I would have said:

I am two in one,

like the wings of a swallow ,

content with bringing good omen

when spring is late.

*

He loves a country and he leaves.

[Is the impossible far off?]

He loves leaving to things unknown.

By traveling freely across cultures

those in search of the human essence

may find a space for all to sit…

Here a margin advances. Or a centre

retreats. Where East is not strictly east,

and West is not strictly west,

where identity is open onto plurality,

not a fort or a trench/

*

Metonymy was sleeping on the river’s bank;

had it not been for the pollution

it could have embraced the other bank.

*

– Have you written any novels?

ï I tried… I tried to retrieve

my image from mirrors of distant women.

But they scampered off into their guarded night.

Saying: Our world is independent of any text.

A man cannot write a woman who is both enigma and dream.

A woman cannot write a man who is both symbol and star.

There are no two loves alike. No two nights

alike. So let us enumerate men’s qualities

and laugh.

– And what did you do?

ï I laughed at my nonsense

and threw the novel

into the wastepaper basket/

*

The intellectual harnesses what the novelist can tell

and the philosopher interprets the bard’s roses/

*

He loves a country and he leaves:

I am what I am and shall be.

I shall choose my place by myself,

and choose my exile. My exile, the backdrop

to an epic scene. I defend

the poet’s need for memories and tomorrow,

I defend country and exile

in tree-clad birds,

and a moon, generous enough

to allow the writing of a love poem;

I defend an idea shattered by the frailty

of its partisans

and defend a country hijacked by myths/

*

– Will you be able to return to anything?

ï My ahead pulls what’s behind and hastens…

There is no time left in my watch for me to scribble lines

on the sand. I can, however, visit yesterday

as strangers do when they listen

on a sad evening to a Pastorale:

“A girl by the spring filling her jar

“With clouds’ tears,

“Weeping and laughing as a bee

“Stings her heart…

“Is it love that makes the water ache

“Or some sickness in the mist…”

[until the end of the song].

*

– So, nostalgia can hit you?

ï Nostalgia for a higher, more distant tomorrow,

far more distant. My dream leads my steps.

And my vision places my dream

on my knees

like a pet cat. It’s the imaginary

real,

the child of will: We can

change the inevitability of the abyss.

*

– And nostalgia for yesterday?

ï A sentiment not fit for an intellectual, unless

it is used to spell out the stranger’s fervour

for that which negates him.

My nostalgia is a struggle

over a present which has tomorrow

by the balls.

*

– Did you not sneak into yesterday when

you went to that house, your house

in Talbiya, in Jerusalem?

ï I prepared myself to sleep

in my mother’s bed, like a child

who’s scared of his father. I tried

to recall my birth, and

to watch the Milky Way from the roof of my old

house. I tried to stroke the skin

of absence and the smell of summer

in the garden’s jasmine. But the hyena that is truth

drove me away from a thief-like

nostalgia.

– Were you afraid? What frightened you?

ï I could not meet loss face

to face. I stood by the door like a beggar.

How could I ask permission from strangers sleeping

in my own bed… Ask them if I could visit myself

for five minutes? Should I bow in respect

to the residents of my childish dream? Would they ask:

Who is that prying foreign visitor? And how

could I talk about war and peace

among the victims and the victims’ victims,

without additions, without an interjection?

And would they tell me: There is no place for two dreams

in one bedroom?

*

It is neither me nor him

who asks; it is a reader asking:

What can poetry say in a time of catastrophe?

*

Blood

and blood,

blood

in your country,

in my name and in yours, in

the almond flower, in the banana skin,

in the baby’s milk, in light and shadow,

in the grain of wheat, in salt/

*

Adept snipers, hitting their target

with maximum proficiency.

Blood

and blood

and blood.

This land is smaller than the blood of its children

standing on the threshold of doomsday like

sacrificial offerings. Is this land truly

blessed, or is it baptised

in blood

and blood

and blood

which neither prayer, nor sand can dry.

There is not enough justice in the Sacred Book

to make martyrs rejoice in their freedom

to walk on cloud. Blood in daylight,

blood in darkness. Blood in speech.

*

He says: The poem could host

loss, a thread of light shining

at the heart of a guitar; or a Christ

on a horse pierced through with beautiful metaphors. For

the aesthetic is but the presence of the real

in form/

In a world without a sky, the earth

becomes an abyss. The poem,

a consolation, an attribute

of the wind, southern or northern.

Do not describe what the camera can see

of your wounds. And scream that you may hear yourself,

and scream that you may know you’re still alive,

and alive, and that life on this earth is

possible. Invent a hope for speech,

invent a direction, a mirage to extend hope.

And sing, for the aesthetic is freedom/

*

I say: The life which cannot be defined

except by death is not a life.

*

He says: We shall live.

So let us be masters of words which

make their readers immortal — as your friend

Ritsos said.

*

He also said: If I die before you,

my will is the impossible.

I asked: Is the impossible far off?

He said: A generation away.

I asked: And if I die before you?

He said: I shall pay my condolences to Mount Galilee,

and write, “The aesthetic is to reach

poise.” And now, don’t forget:

If I die before you, my will is the impossible.

*

When I last visited him in New Sodom,

in the year Two Thousand and Two, he was battling off

the war of Sodom on the people of Babel…

and cancer. He was like the last epic hero

defending the right of Troy

to share the narrative.

*

An eagle soaring higher and higher

bidding farewell to his height,

for dwelling on Olympus

and over heights

is tiresome.

*

Farewell,

farewell poetry of pain.

Jaskmal Bains is a post-graduate in English. She is a sub-editor with The Kashmiriyat.