Bhat Yasir

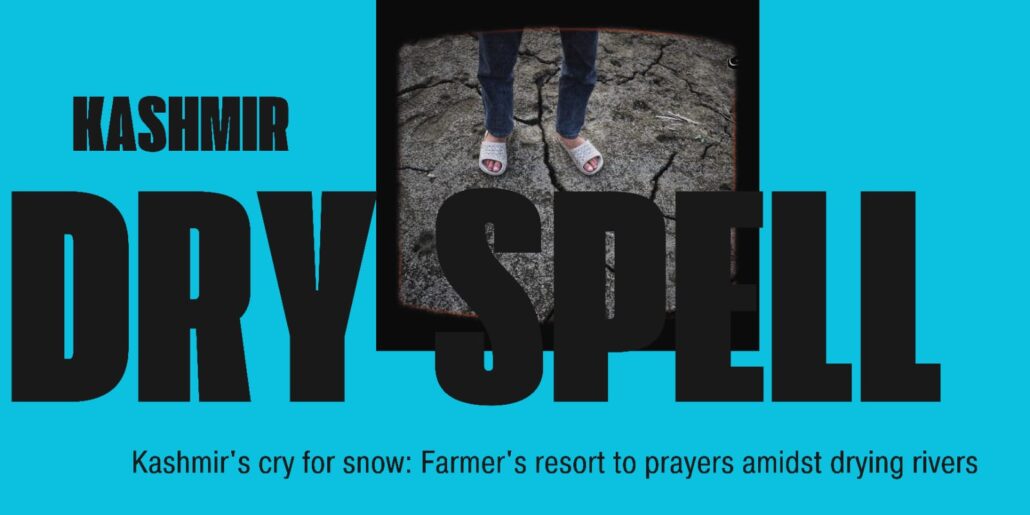

Every morning, Abdul Ahad Khan, a 59-year-old farmer from Batengoo in Khanabal, makes a pilgrimage to the banks of the Jhelum, a mere 400 meters from his home. “I come here every morning to check the water levels of Jhelum. This water level in Jhelum is our lifeline. Our food produce, agriculture, water, and everything else depend on this water. But it looks like it has not been snowing up in the mountains. It worries me. Kashmir has seen the worst of times for the last four years,” laments Khan.

As on Sunday, water level in the Jhelum River has reached its lowest point due to a prolonged dry spell in Kashmir. “River Jhelum was flowing at -0.75 feet at Sangam (Anantnag district) and -0.86 feet at Asham (Bandipora district) on Sunday morning. This is the lowest water level in the river,” the officials said. It had dropped to this level at Sangam in November 2017, they said.

Kashmir is experiencing an extended dry spell this winter, marked by minimal snowfall and a staggering 79 percent rainfall deficit recorded for December. Most parts of the valley have witnessed no precipitation in the first fortnight of January.

The iconic Gulmarg ski resort, typically blanketed in snow during this season, stands dry. While the upper reaches of the valley have received a reduced amount of snow, most plain areas of Kashmir remain devoid of snowfall.

The dry weather has led to a surge in bushfires across the hilly areas of the valley. Collaborative efforts by the Forest Department, locals, and deployed Army personnel involve using fire beaters and portable extinguishing equipment to prevent the flames from encroaching upon nearby forests.

An advisory has been issued to residents in forest areas, outlining precautionary measures such as avoiding open flames, reporting suspicious activities, adhering to fire restrictions, planning outdoor activities carefully, and reporting fires immediately. Emergency contact numbers have been provided for swift reporting, emphasizing the crucial role of community involvement in preventing and controlling forest fires.

A senior engineer from the Jal Shakti department warned, “If the present dry spell continues till the end of Chillai Kalan, then we are headed for a miserable summer water situation. Snowfall after the Chillai Kalan hardly replenishes the perennial water reservoirs in the mountains.”

Environmentalists emphasized the impact of climate change on crops and called for urgent attention, particularly in the Himalayan region. Climate change has affected crop production, leading to a decline in apple production.

The Chief Engineer addressed concerns about drinking water shortages, noting that while there is no current scarcity of water in a broader perspective, he acknowledged the severity of the situation, pointing to the low gauge at Sangam in August last year.

He expressed hope for relief with potential snowfall in the higher reaches in the next 15 to 20 days. The reduction in drinking water supply is attributed to climate changes, evident in the valley’s driest September and second-highest temperature since 1934. Environmentalist Ajaz Ahmad emphasized the impact of climate change, citing a record day temperature of 34 degrees Celsius in 2023.

He highlighted adverse effects on crops and called for urgent attention to climate change issues in the Himalayan region, where 60 percent lacks weather stations, emphasizing the need for comprehensive studies of weather and climate.

The impact of the dry spell is already visible on the ground in Kashmir, particularly in Pulwama district,

There has been a depletion of significant water sources, including the renowned Aripal Spring in Tral and Bulbul Spring in Newa Pulwama. The Aripal Spring, a vital drinking water source for multiple schemes, has completely dried up, causing water scarcity in various areas.

The Fisheries Department had to relocate its fish farm near Aripal Spring due to the water source drying up. Bulbul Spring, supporting a water supply scheme for four decades, has also dried up, leading to shortages in multiple villages.

In this situation, authorities have deployed tankers to supply water to affected villages, emphasizing the need for proactive measures to prevent further escalation of the crisis.

A prayer cry for snow

In response to these challenging conditions, farmers like Abdul Ahad Khan and thousands more turn to prayers, echoing across the Kashmir valley. These prayers, fervently held for snowfall, witness massive participation, reflecting the collective concern for the region’s water resources.

In Anantnag’s Jamia Masjid, a multitude of worshippers gathered for prayers fervently seeking the blessing of snowfall. Here, a Moulana emphasized the indispensable nature of snowfall for Kashmir’s sustenance. “I am a farmer myself, and I know the losses we have incurred during the last four years are immense. The tourism industry may be suffering, but they will earn during the summer months. However, if snowfall does not occur during Chillai Kalan, we will suffer for the whole year,” the cleric addressed the vast gathering.

Devotees extended their prayers at the Khanqah of the local saint Hazrat Baba Hyder Reshi in the heart of Anantnag town, imploring Allah for the much-needed snowfall.

Highlighting the urgent need for precipitation, the official stressed, “Our surface water sources are not getting recharged in the absence of snowfall and rainfall, so precipitation at this juncture is crucial to replenish our sources well in advance for the coming months.”

In the context of the traditional Kashmiri winter, divided into three parts, the initial forty days known as Chilla Kalan hold immense significance. During this period, the lack of snowfall carries profound implications. The chilly wind causes the moisture in the vapor-water to freeze, resulting in intense cold, referred to as Kath Kosh. Icicles embellish the caves of the roofs, creating a picturesque winter landscape. However, the current weather conditions, marked by the scarcity of snowfall, deviate from these typical features of peak Kashmir winter.

Some experts view the Valley’s bare hillsides as indicative of changing global weather patterns impacting the Himalayan region. Environmentalist Nafees Hassan acknowledges the current situation as a harbinger of a worsening climate, while climate change researcher Professor (Dr.) Shakil A Romshoo highlights the correlation between the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) and winter precipitation in Kashmir. The negative NAO during December 2023 and the predicted strongly negative NAO for January 2024 contribute to very low snowfall during this winter.

The scarcity of snowfall not only affects local farmers, as mentioned by Abdul Ahad Khan, but it also dampens hopes for winter tourism in the Valley. Popular destinations like Gulmarg, Sonamarg, and Pahalgam witness a decline in tourist footfall during Chilla Kalan. Gulmarg, a premier ski resort, has been unable to open its slopes, impacting the tourism industry. Despite efforts to transform Sonamarg into a hub for winter sports enthusiasts, the absence of snowfall delays the hosting of these activities.

The overall decline in tourist activity at these destinations, in contrast to their usual bustling atmosphere during Chilla Kalan, reflects the far-reaching consequences of the current weather conditions on various sectors, from agriculture to tourism.

Climate experts link the weather shifts in Kashmir to broader climate change and global warming, warning of cascading impacts on the region’s water resources and agriculture. “We have witnessed in the last few years that the winter period has shortened due to global warming,” stated Mukhtar Ahmed, head of the Indian Meteorological Department’s Kashmir office. “It is not good for this place or, for that matter, any place, as it adversely impacts multiple sectors, be it hydroelectric power generation, tourism, or agriculture.”

The stunningly beautiful Himalayan region of Kashmir, divided between India and Pakistan, claims the disputed region in its entirety.

Recent confirmation by climate scientists that 2023 was the hottest year on record raises concerns. Projections indicate that January will be so warm that a 12-month period will exceed the 1.5-degree Celsius threshold, a target set at the 2015 Paris climate talks to avert the worst consequences of climate change.

Kashmir’s winter traditionally comprises three parts, with Chillai Kalan being the coldest 40-day period starting in late December. The likelihood of snowfall is highest during this phase, crucial for recharging the region’s glaciers that sustain water resources for agriculture and horticulture, the mainstays of Kashmir’s economy, as felt by Abdul Ahad Khan, who has been farming for nearly five decades.

Despite this significance, the region has witnessed distressing environmental fragility. Villagers, heavily reliant on glacial runoff for water, face challenges as farmers like Ahad Khan, dependent on winter precipitation for agriculture, express their distress. In response to water scarcity, some farmers have resorted to converting water-intensive paddy fields to fruit orchards.

The vast temperature fluctuations have given rise to a surge in health issues, particularly respiratory problems affecting many residents. Power cuts, a longstanding crisis despite vast hydroelectric potential, further disrupt daily life, intensifying the sense of gloom and winter stillness in the region.

Despite these challenges, tens of thousands of mainly Indian visitors flock to Kashmir in winter to witness the snow and visit its hill stations and the main city of Srinagar. However, the dry spell has prompted thousands of Muslims in several parts of the region to offer special congregational prayers on Fridays, seeking divine intervention to end the drought.

“We are facing distress and disease in this dry spell,” said Abdul Ahad, a local resident who participated in a prayer meeting in Anantnag’s Bijbehara. “The entire situation is saddening, and I feel people don’t realize the depth of the situation. The governments have done minimal for the farmers of Kashmir. But nevertheless, we are faithful people, and the prayers we are holding across Kashmir will be answered.”

His words echo the sentiments of many in the region, emphasizing the significance of faith and collective prayers amidst the challenges faced by the farming community and the broader populace.