Mir Muntazir Gull

Last month, elections and speculations stirred activity across Jammu and Kashmir. With the polls now concluded, a significant event that will go down deep in history was the participation of banned Jamaat-e-Islami members.

Welcomed by almost all regional and national parties, this event marks a pivotal moment in Kashmir’s history, potentially shaping future discussions on representation and politics in the region.

Despite the anticipation, most Jamaat candidates and other independents failed to retain their deposits, with the exception of Sayar Ahmed Reshi from Kulgam.

Exit polls and several journalists had predicted Reshi’s win, but veteran Marxist Mohammad Yousuf Tarigami retained his seat with a margin of nearly 8,000 votes.

Jamaat-e-Islami’s engagement in electoral politics is not new; it dates back to the late 1960s. According to Tareekh-e-Islami, the official history of Jamaat-e-Islami (Page 243, Part 2) by Ashiq Kashmiri, the Majlis Shura of Jamaat-e-Islami decided in 1962 to participate in elections.

The party contested its first panchayat elections in August 1969; however, it failed to make a significant impact.

In the latter half of the 1960s, Jamaat-e-Islami established a network of schools across Kashmir to educate students. To unify these institutions, the organization founded the Falah-e-Aam Trust, meaning “welfare for all.”

As noted in Tareekh-e-Islami (Part 2) by Ashiq Kashmiri, the Trust was launched in December 1967 as a non-political entity with the aim of promoting education and humanitarian services.

K. Warikoo, in Religion and Security in South Asia, writes that Jamaat-e-Islami had no significant presence in the state’s political spectrum. Instead, it used mosques in remote villages and Muslim-populated regions to build a “political vote bank.”

In 1971, Jamaat contested the parliamentary elections amid the Plebiscite movement in Kashmir and Sheikh Abdullah’s poll boycott, which called the electoral process “illegitimate.”

One candidate’s nomination was rejected due to his association with Sheikh Abdullah’s Plebiscite Front, which was boycotting elections and advocating for a plebiscite in Jammu Kashmir.

Journalist and Janata Party member Shameem Ahmed Shameem writes that he pleaded the case of Qari Saifuddin, one of Jamaat’s candidates, requesting the court to approve his nomination papers as he had sworn allegiance to the Indian Constitution. However, Bakshi Sahib’s lawyers denied this.

Soon after, Syed Mir Qasim became Chief Minister, and Jamaat-e-Islami J-K was recognized as a political party, allowing it to contest the State Assembly elections in 1972.

Ahead of the 1972 Legislative Assembly elections, Jamaat-e-Islami decided in its Shura meeting to field 22 candidates.

Mir Qasim, then Chief Minister of Jammu and Kashmir, initially believed Jamaat-e-Islami should not have been allowed to participate. He later reflected on their involvement in his book:

“Jamaat-i-Islami was creating doubts about the finality of Kashmir’s accession to India, I told its leaders that this party would not be allowed to fight the elections because it had not accepted the accession. But they said that impression was not correct. The Jamaat candidates would take an oath of loyalty to the Constitutions of India and Jammu Kashmir. After consulting Mrs. Gandhi on this issue, she advised against debarring Jamaat, citing that it would set a precedent that could affect the status of the RSS. Despite this, I warned Jamaat that their nomination papers would be rejected if they did not accept Kashmir’s accession, but they insisted on taking the oath of loyalty to the constitution of India, thus they were allowed to participate.”

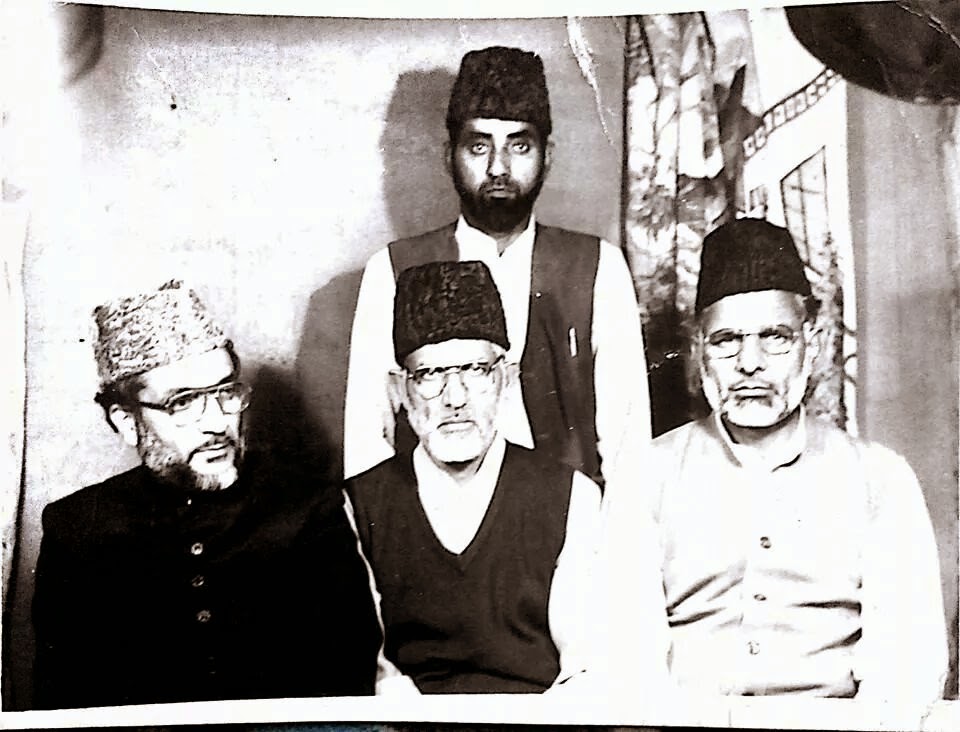

Ultimately Jamaat-Islami won five seats, while nine other candidates of the organisation lost their deposits during the 1972 assembly polls; those who won included Syed Ali Shah Geelani won from Sopore, Ghulam Nabi Nowshehri from Tankipora, Qari Saifuddin from Khanyar, Abdul Razak Mir from Kulgam and Ali Mohammed Dar from Nandi.

Mir Qasim’s tenure also witnessed Jamaat’s contested relationship with state policies. He stated in his book that despite his reservations, Jamaat candidates managed to participate by taking the required oath, winning five seats.

The Jamaat-e-Islami was the only opposition party from Kashmir, while Jan Sangh which won three seats from Jammu also sat in the opposition.

During their speeches in the assembly, the Jamaat-e-Islami did their best to campaign on several issues including the banning of alcohol, while it’s members maintained a pro-islam stance.

This was an extension of the work Jamaat-e-Islami has done during the decade of 1960’s particularly. The unfortunate moment for Jamaat came in 1975 when Indira Gandhi decided to boycott all extremist organisations across India.

During the Emergency imposed by Indira Gandhi from 1975 to 1977, several organizations were banned due to their opposition to the government or perceived threats to national security. Notable among these were the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), the Jamaat-e-Islami, Anand Marg, and various Naxalite groups, including the Communist Party of India – Marxist-Leninist (CPI(ML)).

Syed Ali Shah Geelani in the first part of his autobiography states that Sheikh Abdullah extended the emergency to suppress his opponents, including Jamaat, despite Indira being against imposition of emergency in Jammu Kashmir, however, Ashiq Kashmiri, in his work Tareekh-e-Islami, Part Two, presented a different view, arguing that the ban was imposed by the central government. He noted

“The members sought an answer from the Jammu Kashmir assembly, and official records confirmed that the state had nothing to do with the emergency. The imposition of emergency was the central government’s decision. The official records stated that the ban on Jamaat, like the RSS and several organizations, was also a central government decision during the Emergency.”

Further supporting this perspective, the Secretariat of India (1990), the official records documented:

“On 25 June 1975, Smt. Gandhi introduced the emergency in India. The Sheikh did not agree to political detentions and was against censorship of newspapers in the State.”

Sheikh Abdullah returned power and was unanimously election as the leader of the house in 1975. “This was hard for several sections of the political community in the state to digest,” writes Sten Widmalm.

K. Warikoo writes in Religion and Security in South and Central Asia,“Jamaat-e-Islami protested against the Sheikh Abdullah-Indira Gandhi Accord of 1975 on the grounds that Pakistan and the people of Jammu and Kashmir were not parties to it.”

Altaf Hussain Parra, however, countering this claim writes in, The Making of Modern Kashmir, “The Awami Action Committee and the Jamaat-e-Islamia in the Valley and the Jan Sangh in Jammu left no stone unturned to divert the public disappointment in their favor to carve out a political space in the state.”

In the 1977 elections, held months after Sheikh Mohammed Abdullah declared the controversial Indira-Sheikh Accord null and void, the fears of political factions were cemented as Sheikh Abdullah managed to pull a historic victory in the polls.

The 1977 elections demonstrated Abdullah’s rising influence, which overshadowed Jamaat’s efforts, reducing their presence to just one seat.

Syed Ali Shah Geelani managed to pull off the Sopore assembly segment in north Kashmir with a margin of merely some thirty three votes, as per Election Commission of India records. This was the only seat where Janata Party did not field their candidates against a mutual understanding. The Jamat reciprocated by not fielding any candidates at Tankipora and Khanyar, formerly Jamat had won both of these seats in 1972.

By the following elections, held one year after Abdullah’s death in 1982, Jamaat’s electoral influence had completely diminished from the political landscape of Kashmir. Even Jamat’s strongest candidate, Syed Ali Shah Geelani was defeated with a margin of over four thousand votes in the Sopore assembly segment.

In the following years, political turmoil in Kashmir intensified significantly, marked by defections and betrayals. In July 1984, Ghulam Mohammed Shah, with the support of the Indian National Congress and only eight elected MLAs, overthrew the Farooq Abdullah-led National Conference government. The subsequent years witnessed further instability, leading to the imposition of governor’s rule in the former state. Amid this political chaos, Farooq Abdullah eventually returned to power, and during this period of upheaval, the Muslim United Front emerged—a coalition of various religious and political factions from Kashmir.

In March 1987, Jamaat-e-Islami contested under the Muslim United Front (MUF) banner. Despite widespread allegations of rigging, MUF, supported by Jamaat, secured over 30 per cent of the vote. Many Jamaat members, who contested these elections, later narrated that the rigging in 1987 was a crucial reason for their eventual withdrawal from electoral politics.

Two members of Jamaat e Islami, Syed Ali Shah Geelani won from Sopore and Abdul Razak Mir (killed on 22 November 1995), won from Kulgam, however, Ghulam Nabi Sumji who contested on Ummat e Islami ticket from Home Shalibgh in Anantnag later joined Jamaat e Islami.

Although Jamaat formally quit electoral participation in 1989 two years after the rigging of 1987, their resignation letters cited:

“Lack of democracy and freedom of expression, government atrocities, attacks on Islam, and the anti-democratic and unconstitutional nature of government policy.”

Since then, the Jamaat e Islami stayed away from direct participation in electoral process and in 2019, the Indian government impose five-year ban on Jamaat, citing links to banned militants groups like Hizbul Mujahideen.

Since then, 77 properties associated with Jamaat have been seized across Jammu Kashmir, while several leaders of the organisation are in jails.

Earlier this year, Jamaat-e-Islami announced its return to electoral politics after a 34-year hiatus, however, of the eight candidates the organization fielded as independents, most lost their deposits. In Sopore, Jamaat candidate Manzoor Ahmed Kaloo received only 406 votes, a significant decline in a constituency that was once a stronghold of the late Hurriyat leader Syed Ali Shah Geelani.

Jamaat’s best performances were in Kulgam and Zainapora, where candidates Sayar Ahmed Reshi and Aijaz Ahmed Mir finished in second place, losing by margins of 8,000 and 13,000 votes, respectively.

Jamaat’s electoral journey reveals a turbulent history shaped by socio-political dynamics, government policies, and external influences.

Despite its early attempts to establish a political foothold, its role in Kashmir’s political landscape has been consistently challenged by both local and central authorities.

Mir Muntazir Gul is an academic from Anantnag and the former press secretary of Muslim United Front.