Sumit Garg

For centuries, Kashmir has captivated poets, its landscapes immortalized in verse. However, the poetic portrayal of Kashmir has undergone a profound shift, reflecting the socio-political turmoil that has gripped the region.

The partition of 1947, subsequent wars, and prolonged conflict have transformed the identity of Kashmiris, often forcing them to choose between multiple ideologies unwillingly.

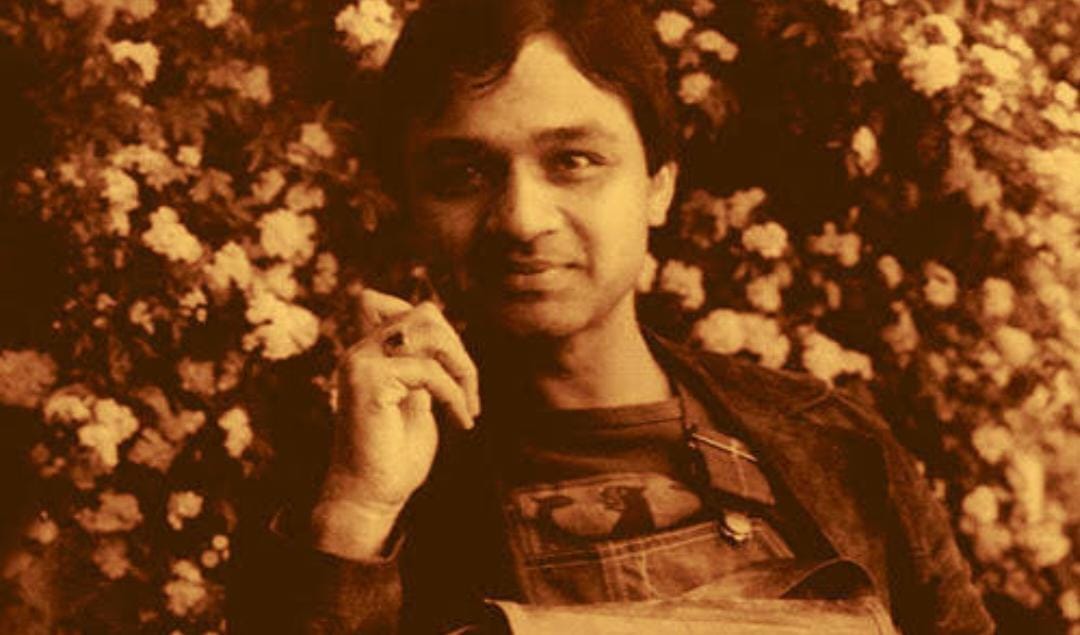

This shift has also altered the thematic focus of Kashmiri poetry—from mysticism and nature to conflict and displacement. Agha Shahid Ali emerges as a crucial figure in this transformation, chronicling the heartbreak of exile and the erasure of cultural memory through his poetry.

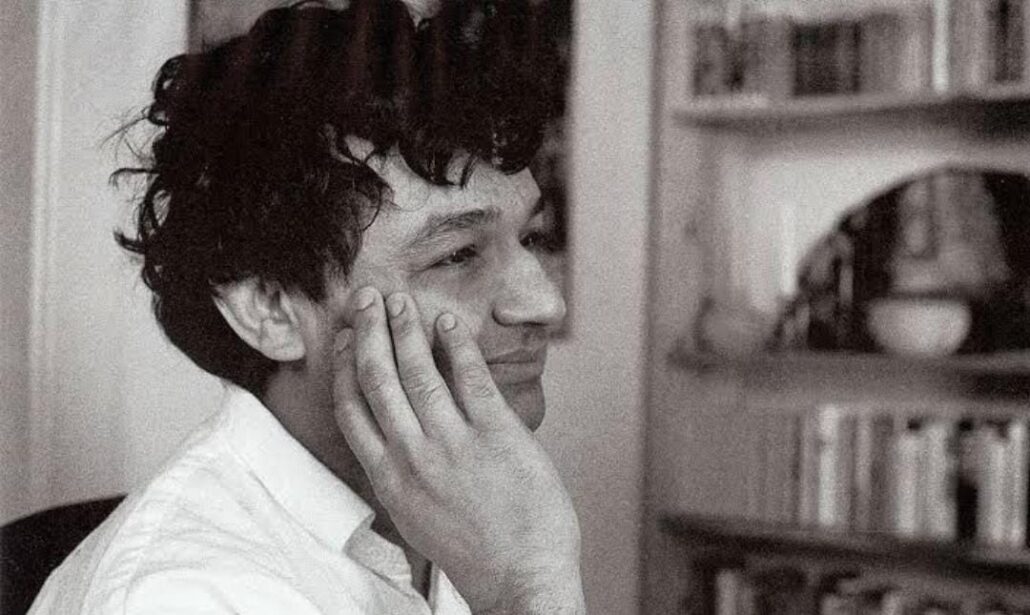

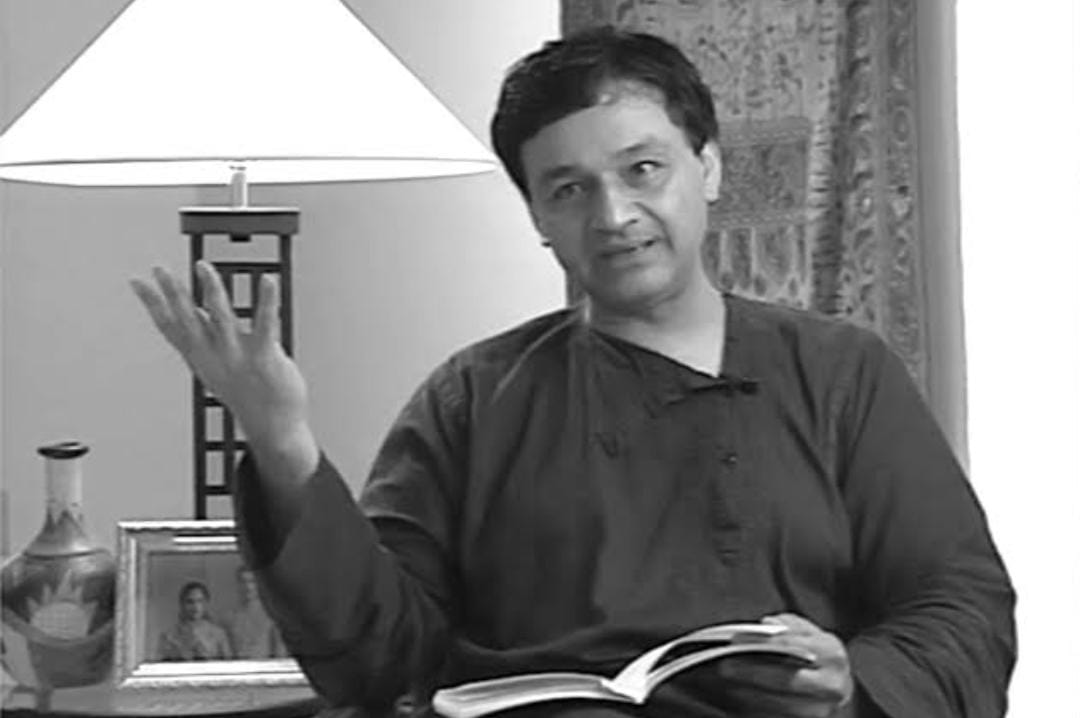

Born in Delhi and raised in Srinagar, Agha Shahid Ali later moved to the United States, where he established himself as a poet of exile and memory. Educated at the University of Kashmir, Hindu College, and later at Pennsylvania State University and the University of Arizona, Agha Shahid inhabited a cultural space shaped by multiple influences—Kashmiri, Indian, and Western.

Though he identified as an American poet writing in English; Urdu, remained integral to his poetic sensibilities. His poetry reflects the deep wounds of Kashmir’s turmoil, capturing the silence that exile imposes on memory and the impossibility of returning to a home that no longer exists as he once knew it.

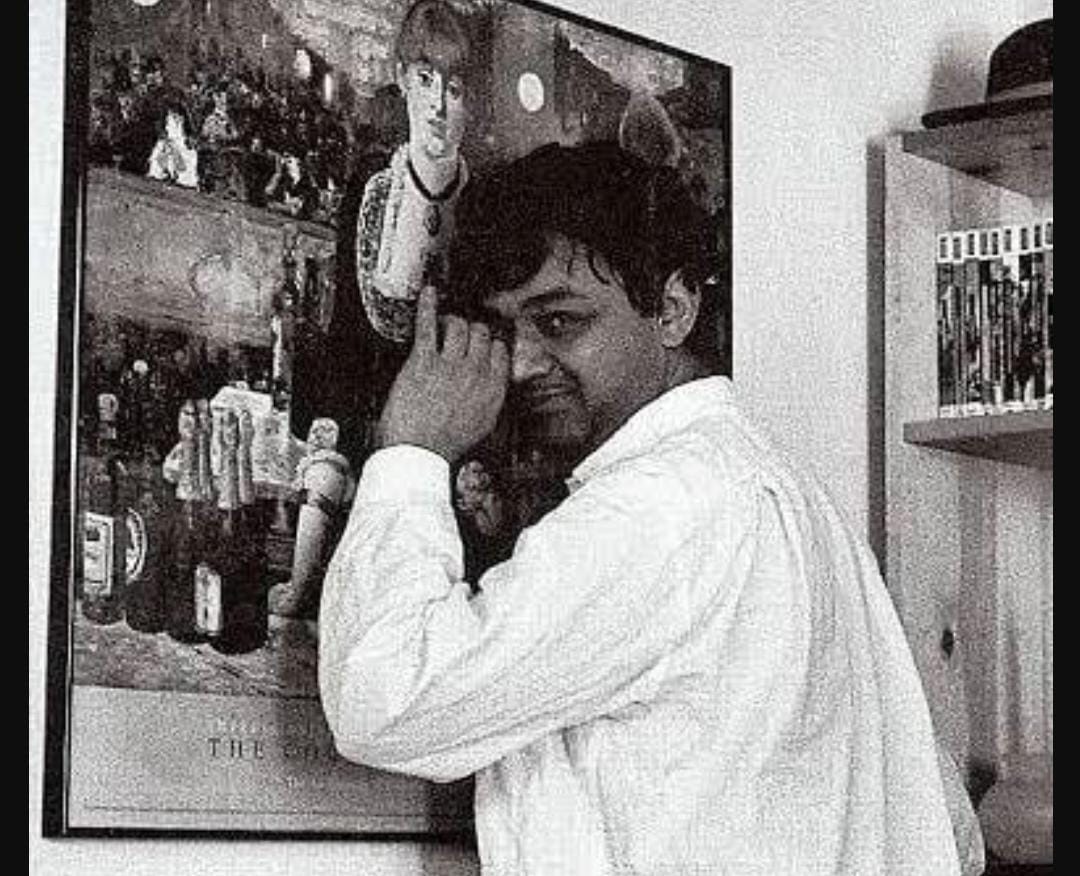

Agha’s work conveys a personal anguish, a yearning for a lost homeland (Kashmir), and an acute awareness of historical injustices. His poems function as a bridge between the past and present, blending the lyrical with the brutal realities of injustice against his own people.

Agha’s poetry repeatedly invokes Kashmir, both as a physical space and as a symbol of loss. In his collected works, the name “Kashmir” appears ninety-four times, particularly in ‘The Half-Inch Himalayas’ (1987) and ‘The Country Without a Post Office’ (1997). His poetry constructs an elegiac narrative, mourning the paradise that has been transformed into a land of unending tragedies.

In ‘The Country Without a Post Office’, Agha’s use of repetition serves as an invocation, a desperate attempt to reclaim Kashmir through language: “Kashmir, Kaschmir, Cashmere, Qashmir, Cashmir, Cashmire, Kashmir, Cachemire, Cushmeer, Cachmiere, Cašmir.”

Like a chant, these variations of Kashmir’s name reflect the fragmented identity of a homeland fractured by history. The poet forces his readers to confront the chasm between what Kashmir once was and what it has become.

Agha’s poetry often alludes to Kashmir as a ‘paradise lost’, echoing John Milton’s ‘Paradise Lost’. In ‘Farewell’, he writes of a Kashmir abandoned by its guardian: “Who is the guardian tonight of the Gates of Paradise?”

Similarly, in ‘I See Kashmir from New Delhi at Midnight’, Agha introduces the character ‘Rizwan’, named after the Arabic term for the gatekeeper of paradise. Rizwan, however, is depicted as a ghostly presence wandering the streets of Srinagar, symbolizing the erasure of Kashmir’s once-sacred status.

The motif of paradise is further complicated in ‘The Last Saffron’, where Agha recalls the famous couplet: “If there is a paradise on earth, It is this, it is this, it is this.”

But in Agha’s poetry, these words ring hollow, juxtaposed against the imagery of a bloodstained Kashmir.

Agha frequently employs saffron and paisley as symbols of Kashmir’s cultural richness and its suffering. Saffron, a prized Kashmiri spice, becomes a metaphor for both beauty and destruction. In ‘Farewell’, he laments: “Have you soaked saffron to pour on them?”

Here, saffron, traditionally associated with divinity and ritual, transforms into a symbol of grief and loss.

Paisley, a teardrop/ almond-shaped motif associated with Kashmiri craftsmanship, also recurs in Agha’s work. In ‘The Country Without a Post Office’, paisley becomes the currency in a land where even communication is silenced: “They brought cash, a currency of paisleys to buy the new stamps.”

This line evokes the eerie reality of a Kashmir where letters go undelivered, and voices are suppressed. The paisley pattern, once a symbol of Kashmiri artistry, now symbolizes a Kashmir under siege.

Agha’s poetry is not merely a lament; it is an act of resistance. In ‘I See Kashmir from New Delhi at Midnight’, a boy’s shadow runs through the streets under curfew, searching for its lost body. The poem presents an interrogation scene where the only response a tortured prisoner can muster is: “I can’t remember”.

Through such stark imagery, Agha gives voice to Kashmir’s silenced victims. His poetry documents both personal and collective suffering, refusing to let Kashmir’s pain be forgotten.

Agha Shahid Ali’s poetry serves as an enduring testament to Kashmir’s transformation from an idyllic paradise to a landscape of loss and longing.

By weaving together cultural memory, historical trauma, and lyrical beauty, Agha’s work keeps alive the spirit of a homeland that now exists only in memory.

Agha does not offer solutions or political prescriptions—his poetry is, instead, an elegy for a Kashmir that once was, and a lament for what it has become.