Fizala Khan

The downtown area of Central Kashmir’s Srinagar district is renowned for protests resisting atrocities. Locally called ‘Shehr – E – Khaas’, the area that was settled 2000 years ago in 3rd BC by Raja Pravarsena, has been the historical hub of architecture, heritage and old markets. The heritage and memorabilia of the ancient settlement has faded, and it now bears the weight of reports that document a large number of killings, disappearances, torture and arbitrary detentions in the area.

The region, once called the ‘Venice of the East’ is deserted, because of the absence of peace.

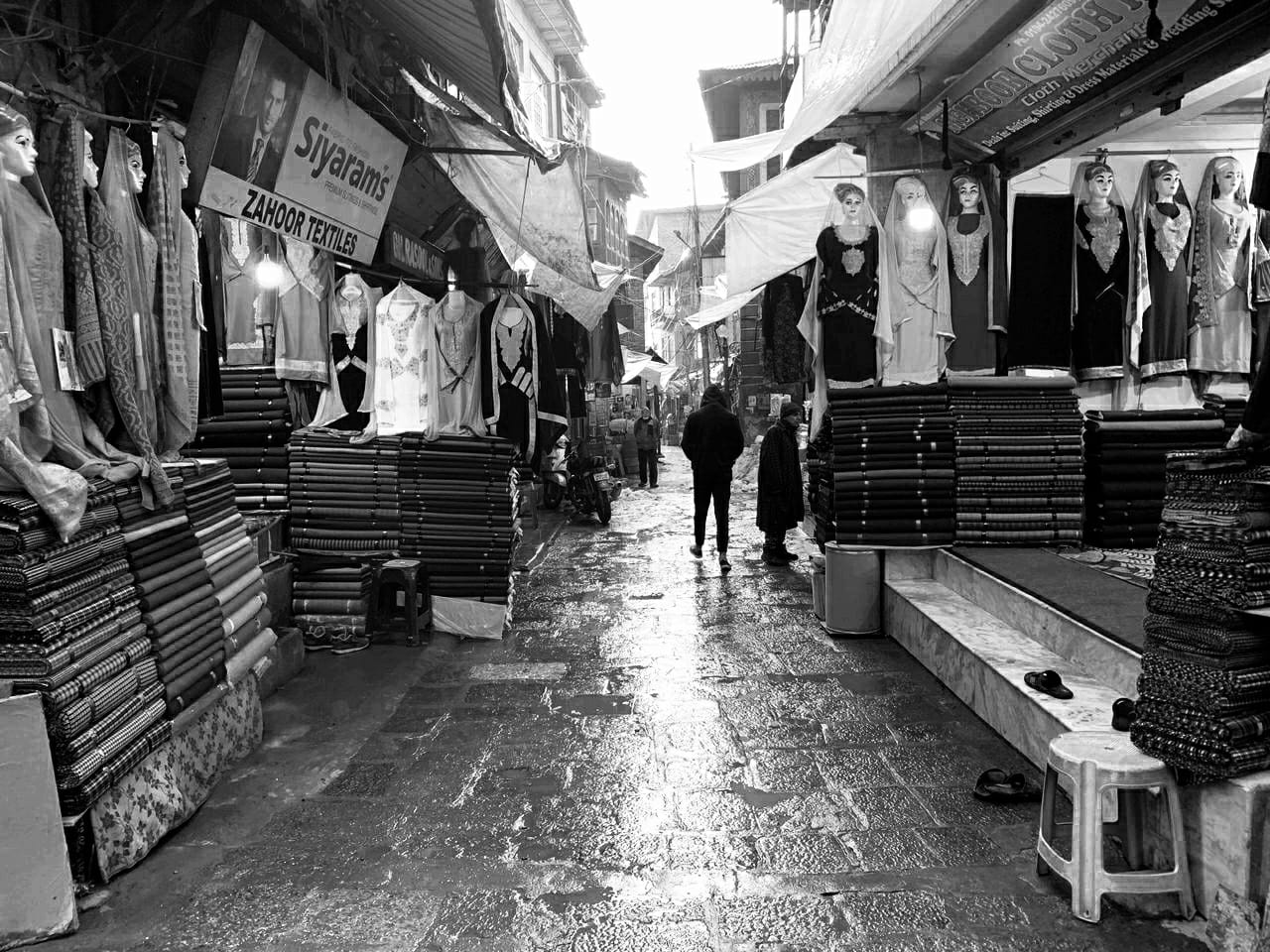

In Khanka Mohalla of Zaina Kadal, Gaade Koche market strives in a narrow lane that disappears after a walk before Bohri Kadal, and was once marked pivotal, when locals would linger around, buying spices and other necessities. Now, the market leaves a haunting mark of silence and darkness, because of the killings that took place on the 10th of February in 1995, which also happened to be the 10th day of Ramadaan.

The forces while cordoning off a large area, under the pretext of search operations, resorted to firing indiscriminately on shopkeepers and civilians. They opened fire on the narrow business street in Gaade Koche, killing 6 shopkeepers and injuring 38 others.

Plato, closely associates memory, recollection, and shadows the slow learner as forgetful and possessing a poor memory. Prima facie, then, Aristotle’s separation of memory (and being “slow”) from recollection (and being “quick”) dawns on the memory of ‘longing’ and ‘lost belonging.

While the eyewitnesses stress on wanting to forget the haunting memory, stressing on how the aroma of spices and old jute bags with grains will never overshadow the smell and the sight of blood, that wreaked havoc and latches on to them as a foreign entity that is inseparable. The old heritage market, has now become a witness to mayhem, terror and merciless manslaughter.

The thin and narrow lanes of Gaade Koche are fixated with cemented Devri stones, with old structures of a ‘souk’ like market, pots, potters, aromatic spices that distract one’s attention from the haunting memoir. The dried vegetables ‘Hokh Syun’ and herbs of the market, brings minimum, but unsatisfactory wage to the shopkeepers. “It is not even enough to suffice through the month. One day’s sale turns into a hand-to-mouth situation. While the shops that now sell wedding essentials have a better turnover than us,” one of the shopkeepers said.

Today, the lanes of Gaade Koche are bustling with business activity till 10 PM, but the remnants of a massacre are still visible.

The stationary bunker of BSF nearby was attacked upon by Militants of Harkat – Ul – Ansar, resulting in a violent clash between the forces and Pheran – clad combatant. Before the forces could retaliate, the rebels fled the area.

Enraged by the incident, BSF unleashed a torrent of violence on the streets, firing indiscriminately and bumping off whomever they could lay their hands on, irrespective of their involvement with the “crime”.

Seven people fell to the bullets of the forces. While some eyewitnesses also claim, that women from the surrounding houses were beaten and injured after the merciless firing.

“The BSF personnel,” Daily Kashmir Times report quoting victims wrote, “collected inmates of these houses in different rooms and tortured them.”

“The firing was so extreme and went on for so long, it felt like the noise and the echoes will never end,” said another eyewitness.

“We just wanted to live, there was nothing in between, I did not care about anything, but the safety of my son and myself, I only thought of the noise, the heavy machine gun fires that still ring through my ears, the marching off their boots, the blood-stained walls and bodies, it all feels like yesterday, I do not know why I was not dead, I wanted to be,” an eyewitness told The Kashmiriyat.

“Another BSF personnel barged into my store and asked me to come out, he frisked me and slapped me. I felt humiliated. Nobody wants to live through the humiliation and exist. I would have preferred being dead,” he said.

Amid unrestrained firing, a posse of BSF men stormed into his store. “Come out,” they said, sternly.

Some eyewitnesses claim, that the armed men left them to live in fear, while some assert, that their cordial behavior as a shopkeeper saved their life.

The firing subsided at 8:00 in the night.

Eyewitnesses also claimed, that there was a crackdown after the firing ended and officials disclosed that forces had gunned down some seven civilians during shootout. “They told us that the corpses were lying at Amar Singh Club.”

Another eyewitness claimed that the gunshots were audible near the Khanqah shrine. He quickened his pace and started running towards the firing scene. “There was a huge crowd of people who listened helplessly to the firing and cries,” he said.

The Gaade Koche remained shut for days after the killings of the shopkeepers. The incident coincided with Maqbool Bhat’s death anniversary, evoking angry protests by the traders and letting the tenuous situation snowball into an altercation with armed forces.

As part of the enquiry, the eye-witnesses were summoned in the Police station to identify the perpetrators. Stoic faces of BSF personnel present during the time of carnage were lined in front of them. “Like the typical scenes of Bollywood movie, we were asked to identify the killers,” said a cloth merchant who recalled details of the attack.

Nearly twenty six years later, the traders seem to have picked their way through the decade of mourning. Each of them gives an impression of having gone past the event, trying not to remember it, trying as hard as they can to recall the day with a pretended ignorance. In the Maharaj Gunj police station, among the heap of dusty ledgers, a file encloses an FIR copy (17/1995) scribbled with details about the massacre.

The perpetrators could not be traced and the case was closed.

The haunting lanes and silence in the market creates a very strong and bitter feeling of betrayal. It takes an irritatingly objective look, though not explicitly, at the ‘oral narrations’ of the killings, that is less talked of. It marks how terror and propaganda manifested the hearts of ‘Shehr-E -Khaas’.

Another shopkeeper spoke to The Kashmiriyat and said that he still has the scars of the wound he received on his hands while defending his son. He made sure his wife was safe with his extended family, all hiding in a room after the firing started.

Thousands walked along with the snow – soaked road. Their faces covered in dirt, some in blood.

The armed forces announced their presence with automatic gunfire aimed indiscriminately at men, women and children, vendors, shopkeepers and innocent lives were lost.

“Nothing remains more vivid in my mind than hearing the horror of the survivors and bearing witness to the blood covered curbstones and walls that described the violence. Only a handful managed to escape the massacre,” said Siddique Ahmed, a local shopkeeper.

The memory is fresh in the minds of locals.

Zahoor Bhat, another shopkeeper said, “When I turned to the corner and I saw someone I knew, he was on his knees, he hadn’t gotten far, and the other young men—in my mind it was three, but maybe it was four, maybe five; memory is ruthlessly fickle—they were holding one of them down and encircling him so he couldn’t escape, as someone repeatedly slammed his head against the wall.”

“Then came the loud sounds of the gun machines and machinery of sirens. The chasers froze, and then, the boy I knew, the young man’s body slump and fell. I remember his body on the chessboard shaped wall, his head fleshy and broken. I remember blood on the wall. I found out later he was dead,” he added.

“We are all dead, we just exist in moments, waiting for a bullet to take us,” he concluded.

In Dambudzo Marechera’s ‘Scrapiron Blues’, the last collection of his posthumously published work, he mentioned walls with blood, nearly always violent, glaringly preoccupied with fear and haunted by memory. The connection is not forced, but evidentiary.

‘Dreams Wash Walls’ – in the second piece of the collection, he wrote, “Tony is trying to wash all the blood from the inside walls of his flat,” Tony (the protagonist) is “scrubbing loyally away the blood and gore of history”.

The gory detail of the walls hits him. He clutches his chest. The ants are scurrying about, nibbling bits of the inside of his chest. The size of the task confronting him from all the inside walls of the flat seizes his brain. He hurries into the bathroom for his stiff brush, the soap and bucket.

He washes the walls all morning, as he mourns over spilled blood.

For lunch, he grills two sausages and three strips of bacon. He smooths it all down with yogurt. Then he is back to his work. The walls are his lifetime’s epic.

The blood is his Iliad, his paradise lost, his age is the reason. He states that – ‘it is a superhuman task, trying to wash away all that blood’ and the blood of course, is imagined.

But for Zahoor, the bloodshed and scrubbing the stains of the wall, the cemented narrow road, the disappearing lane and the BSF bunker, that was replaced by a CRPF troop, has marked a hallow and imprinted fright on his existence. The spices, the gold souks, the wedding garments, nothing can change the horrific killings for him, that took place at Gaade Koche market on the 10th of February in 1995.

Far away from home, while compiling this report, home comes to me – in the aroma of spices from the old wooden attics of ‘Shehr – E – Khaas’, the maze of the alleys, the beauty and haunting silence of the streets, crowded with armed men, the trauma, the images and the stories, graced the wall of my memory forever.

The Names have been changed or concealed on request.