Prerna Bhat

“Beyi yi wathwo, bey yi saet, asih kyah chhu door karaan?” (Translation: Let us sit together again, let us walk together—what is it that keeps us apart?)

Lalita Raina, like thousands of Kashmiri Pandits, shared an intimate friendship with her Muslim peers. In January 1990, Lalita Raina, also called Laleh, was forced to leave behind everything she held dear. As a college-going young girl with predominantly Muslim friends, the prospect of bidding farewell to her life in Kashmir weighed heavily on her.

Prem Nath Bhatt’s writings, particularly an article in Martand on 17-3-1989, had highlighted attacks on minority shrines, including Gurtum Nag, a local Hindu temple claimed by Muslims in response to political plans. The aftermath of his death was catastrophic, with growing tensions preventing Shayla and Lalita from meeting as more Kashmiri Pandits fell victim to violence.

The situation escalated with the killing of ML Bhan on January 15, 1990, and the subsequent circulation of stories fueled fear among the community. Threatening posters urging Pandits to leave Kashmir immediately appeared, and a blackout gripped the valley on the night of January 18-19, 1990. Inflammatory messages broadcasted through various means compelled Kashmiri Pandits to face a dire choice: leave, convert, or face death.

The absence of established communication channels led to the rapid spreading of rumors, intensifying the atmosphere of fear and uncertainty for the entire Kashmiri Pandit community.

The stories of “sloganeering from mosques” in parts of Srinagar coupled with multiple rumours started doing rounds across Kashmir and the “threatening posters” added to the fear.

For decades, the relationship between Kashmiri Pandits and Kashmiri Muslims was marked by deep cultural and social bonds, rooted in shared traditions, language, and values. However, over the years, this harmony was strained by government policies that historically manipulated the region’s demographics, politics, and communal ties for strategic gains.

What began as administrative decisions gradually evolved into policies that deepened the divide and entrenched mistrust between the two communities. Decades later, this separation is not merely a relic of the past but an ongoing strategy, executed subtly and often unnoticed by the world.

The most significant rupture occurred in 1990 when targeted killings and threats forced thousands of Kashmiri Pandits to flee Kashmir. While this exodus was undeniably tragic, the government’s response only deepened the divide.

Instead of fostering reconciliation, authorities resettled Pandits in isolated camps, far from their homeland, without any substantial effort to reintegrate them into Kashmiri society. Their suffering became a political tool, frequently invoked for political gains, but never genuinely addressed, leaving the wounds of separation unhealed.

For Kashmiri Muslims, the 1990s were marked by crackdowns, disappearances, mass incarcerations, and a climate of fear under heavy militarization. While Pandits were displaced, Muslims remained in a landscape defined by repression and human rights abuse.

The government not only failed to protect the Pandits but also ensured that Muslims were perceived as the “other,” unjustly held responsible for a tragedy rooted in governance failure rather than inter-community hostility.

In the following years, a systematic effort was made to keep Kashmiri Pandits outside their homeland rather than reintegrating them with dignity. Vague promises of return were frequently made. Planned townships, jobs, and security measures remained largely on paper, leaving displaced Pandits in perpetual uncertainty.

Meanwhile, successive governments used the exodus narrative to justify heavy-handed policies in Kashmir without acknowledging the underlying alienation and mistrust.

Today, the divide persists, reinforced by new policies that undermine reconciliation. The unilateral abrogation of Article 370 in 2019 was presented as a step towards “national integration” but has instead deepened this existing alienation.

The move did not follow the constitutional provisions of dialogue with the political representatives of the state, in fact, most of them, including three former Chief Ministers were detained and subsequently booked under draconian laws.

The move also sidelined Kashmiri voices and disempowered both communities. Consequently, they remain divided, unable to collectively question the state’s role in their shared predicament.

The government’s approach to Kashmiri Pandit issues remains performative. Political parties, especially during elections, frequently invoke the exodus to justify regional policies, but no real progress has been made toward safe, voluntary repatriation.

Those who do return are often placed in segregated housing, reinforcing the very separation that needs to be dismantled. Meanwhile, Kashmiri Muslims continue to live under military presence and surveillance, constantly facing suspicion about their loyalty to the Indian state.

The most damaging aspect of this state-driven divide is how it shapes narratives about Kashmir. In the Indian mainstream discourse, Kashmiri Pandits are portrayed as victims of Muslim neighbors, ignoring the political context behind their exodus. Conversely, Kashmiri Muslims are stereotyped as aggressors, their grievances dismissed.

This selective storytelling ensures that both communities remain alienated, unable to reconnect and reclaim their once-shared bonds.

What goes largely unnoticed is the obscure strategy behind this division. Kashmir, where Pandits and Muslims stand together for justice, keeping them apart ensures fragmented struggles and muted voices.

Instead of acknowledging their shared suffering, a narrative of polarization, depicting Pandits as victims and Muslims as aggressors has been fostered in mainland India. Yet, the reality is far more complex: both communities have suffered—albeit in different ways—and both continue to bear the consequences of decisions made far from their homeland.

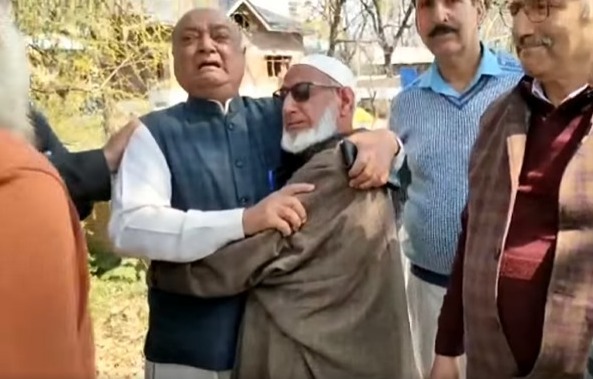

The path to reconciliation lies not in government schemes but in genuine, grassroots efforts that allow Pandits and Muslims to reconnect beyond imposed narratives.

The state has consistently failed to facilitate this. True peace can only emerge when both communities recognize that their struggle is not against each other.

(Prerna Bhat is a massive communication student at Delhi’s Jamia Millia Islamia. The views expressed by the author are her own)