Zainab Rauf

“We are sons of this soil,” says Jaipal Singh, who recently celebrated his 72nd birthday in his Baramulla residence. Before I ask my first question, Singh, a member of the Sikh Missionary College and Guru Harkrishan Jeevan Jot society (GHJJS) Kashmir, is ready to lead me to what exactly our conversation should be about.

The continuous systemic ignorance of the plight of Kashmir’s integral micro-minority community; Kashmiri Sikhs, the fear of rootlessness due to economic distress, the undying love for their motherland despite the conflict, and the unbreakable bond with their Kashmiri kin.

Systemic Ignorance

“Are we children of a lesser a god? Why are our basic rights being snatched away from us?” Jaipal Singh says about the failure of every passing government to grant Minority Status to Kashmiri Sikhs, despite being a micro-minority that too from a conflict region.

While all Kashmiris are suffering the reality of conflict and the prospect of more violence, devastation and poverty, we often tend to not pay heed to the burden of the conflict on the more vulnerable segments of our society.

“I will say it from my heart, Kashmir is heaven for us”, says Dr Jangbhadur Singh, Associate Professor at Department of Pathology SKIMS Medical College.

“We have apnapan (togetherness), our people; sitting, living, dying, marrying, singing, all together. We have till now never felt any faraq (difference) amongst each other,” Dr Jangbhadur continues, “But we have time and again been neglected by the government.”

Making 0.88% of the population of Kashmir, the long pending demand of a Minority Status of Kashmiri Sikhs till now has led to the failure of the formalized process of studies, research, and policies on matters specifically related to the empowerment of Kashmiri Sikhs.

73 years without a Minority Status, Kashmiri Sikhs have been denied their democratic right of fair participation in education institutions and job positions in Jammu Kashmir and across India, which cripples the possibility of their growth on the socio-economic ladder and the mere possibility of their existence lasting as a unique community in the long term.

What’s more important is that even after the colossal reason for revocation of Article 370 by the Modi government, ‘justice’ or rather ‘liberation’ of Kashmir’s minorities, the voices of Kashmiri Sikhs, like always, have been majorly sidelined.

“I believe it’s because we Sikhs don’t make a big vote bank; we have been ignored,” says Angad Singh Khalsa, a prominent Kashmiri student activist.

Post-August 5, it is for the first time in the history of Jammu Kashmir that no Kashmiri Sikh has been taken as a member of Public Service Commission in Kashmir and the Indian government has still not cleared the orders regarding the coverage of Sikhs under the Pahari speaking category, a language integral to Kashmir’s ethnicities.

“We speak a dialect of Punjabi that is not like the Punjabi spoken by Sikhs in other regions. 60% of our language might not match with the Punjabi spoken by others,” says Angad.

Threat of Loss of Identity, Roots, Heritage

It is imperative to acknowledge how ignoring the language of a community that largely communicates or connects to their heritage through it, acts as a major threat to the existence of their unique culture and history as a distinct community from one generation to the next. It not only demotes their place in society but also hinders them in every socio-economic aspect.

“Our culture is intertwined by our language as Kashmiri Sikhs. It allows us to realize and practice our unique identity as Kashmiri Sikhs,” Angad explains.

“The history of our existence is 600 years old in Kashmir,” Jaipal Singh reminds me as he talks about Kashmiri Sikh youth now often asking him about their identity.

He tells me the story that he often tells his students. Guru Nanak Ji travelled to Leh, Kargil, Amarnath, and then to Srinagar where Sufism was thriving and where Braham Das, one of the most eminent of the Kashmiri Pandits, accepted Sikhism, leading to several native Kashmiris following suite.

August 5, 2019, has forced all Kashmiris to question their identity, belonging, rights, and future. But voices of the vulnerable part of our society, Kashmiri Sikhs, have again been disproportionately sidelined.

“I don’t know who I am anymore”, says Kawal Nain Singh, a private sector businessman from the valley residing in Punjab to make a living not possible in an area of conflict. Kawal’s words seem like he had already said them before, he didn’t need a second to think about an explanation.

“My identity is being lost. My culture is Kashmiri, not Punjabi; I don’t match with people here. I have no one here in Punjab,” he continues.

Slow Migration: Religious Persecution or Economic Distress?

Khushdeep Kaur Malhotra, a PhD candidate at Temple University, in her case study on Kashmiri Sikhs, states that although the community is conscious about harm from violence as they live in a conflict zone, religious persecution is categorically stated as a non-issue. Rather it is economic distress from the violence that would eventually make the community leave.

I ask Dr Jangbhadur about the same and he explains, “Our generation never moved out despite the 90’s turmoil as we thought it’s our Kashmir, our people. Although we have suffered a lot, we strived to live here only.”

“We were clear on staying with our people,” he says.

“However, because there is no economic package, reservation, or support from the government we are being forced to move out. If you see the data on our new generation, it indicates how our youth are not getting the recognition and education they deserve. They are aware of the opportunities they are missing out due to everything happening in Kashmir,” adds Dr Jangbhadur.

“We have been raising our voice over and over again and so we have no option but to witness a silent migration to find livelihoods,” Angad explains.

“Outsiders are being brought here to live and for the natives, such circumstances are being created that they are being forced to leave to find jobs. It’s laughable. Everyone is being suppressed. Every Kashmiri, be it Sikh, Muslim, Christian. Especially financially,” Angad says.

On the other hand, Jaipal Singh tells me to address the bigger issue of how economic negligence of any community leads to poorness, and “Poorness leads to internal conflict”.

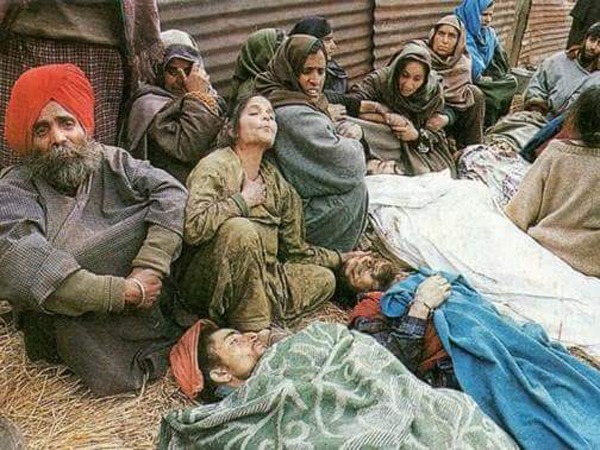

Catching hold of the topic of migration, I ask about the fear of religious persecution and thoughts of leaving Kashmir after events like the Chattisinghpora massacre.

Angad says, “Chattisinghpora did result in communalization between the communities for a few days but within no time, certain things were revealed and realized by community members.”

Jaipal Singh, mentioning that he remembers the pain of Chattisinghpora massacre at the back of his hand, says that the community continuously asked for justice to be served but till date, all government bodies kept the community in limbo.

“Now when we ask again, we feel ashamed,” he says.

According to records made by the Kashmiri Sikh community, more than 100 Sikhs were killed during the turmoil in Kashmir (1990-2020). Both Jaipal Singh and Dr Jangbhadur convey the same message that the socio-economic ignorance of the Kashmiri Sikh community has led to lack of official records, data, books, research papers that give a platform to the truth and narratives of Kashmiri Sikhs.

This brings me to Khushdeep Kaur Malhotra’s groundbreaking research work that uses evidence-based on ethnographic fieldwork where she concludes that despite the violence, Sikhs and Muslims have continued to live closely and that the Sikh community’s decision to keep residing in Kashmir is driven by a combination of economic necessity, attachment to the land, and distrust of India.

Solidarity: 1984 Sikh Massacre, Chattisinghpora Massacre

Playing the scenario in his head, Angad talks about how maybe if his elders had migrated after the Chattisinghpora massacre, they could have gone to government jobs, plots of lands, education quotas. However, he keeps reiterating to me that the community was and is aware that wrong has not only happened to them.

Angad says, “Our elders realized that we are not the only ones suffering but our majority community is suffering equally or even more than us. So, we could not leave.”

Talking about the 1984 Sikh Massacre, Angad says that “Kashmir might have been the only region where no riots happened against Sikhs after the assassination of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. More importantly, that day in Jammu Kashmir maybe two Muslims and three Sikhs were shot dead in protests against attack on Harmandir Sahib (Golden Temple).”

“Imagine in an area already under so much unrest and conflict, the majority community people gave their lives for the minority,” adds Angad.

Angad further states, “We must talk more about the fact that wherever someone has tried to communalize Kashmir, people in Kashmir have always boycotted that person on a large scale. But we have people in every community who are either ignorant or make use of these situations and tarnish the name of the community. But on a larger scale, we have never seen Kashmiri Sikhs being targeted for being Sikh and even if someone did, a large number of people have time and again spoken up against it in Kashmir.”

“We Kashmiris are very politically aware. We know how to behave in situations when we are being played,” says Angad. He further notifies me about “How Kashmiri Sikhs who left Kashmir to live elsewhere, when given a platform in any possible protest regarding Kashmir, always spoke about the wrongs done to ‘us Kashmiris’.”

Government vs Social Discrimination

All four interviewees state that whether the government sidelines the community again and again or not, the majority community needs to know that “to move forward and ‘survive’, we only have each other.”

“We are aware that we might not have sacrificed ourselves in bodies for Kashmir, but we have financially, politically, and socio-economically sacrificed equally as the majority community in Kashmir, that too being a minority. So as a society how you treat and see us matters,” says Angad.

Dr Jangbhadur and Angad both say that the majority community must remember these sacrifices, acknowledge these facts, and then try to genuinely stand with the Kashmiri Sikh community for their rights on society bases. They both agree that “Supporting each other on a social level is imperative for our survival as Kashmiris as a whole.”

This makes me ask Jaipal Singh if all Kashmiris often make donations to Kashmiri Sikh based NGOs, to which he replies “To be honest, no.”

Jaipal Singh’s answer only worries me about the already limited capacities of humanitarian organizations in Kashmir, lack of access, and inability to monitor aid distribution to everyone, which can further exacerbate the vulnerabilities of endangered communities; the Bakarwals, the Gujjars, Kashmiri Sikhs, Kashmiri Christians, and many more.

I also ask Angad about the hurdles he faces as a Kashmiri Sikh student studying in Kashmir, to which he replies very calmly, “See, we are two to three Kashmiri Sikh students in my university class amongst the many majority kids. So, these two kids are the social responsibility of the majority community. They have to see that these kids are not discriminated against based on being minorities. There the majority community has to act as a shield. They must stand up with us.”

Way Forward

As I ask for final comments, all interviewees ask their Kashmiri brothers and sisters to stand by the Sikh Community when they demand and peacefully protest for what is rightfully and democratically theirs as a micro-minority community amid conflict; minority status, language rights, education and job quotas/protection etc.

Angad, like every Kashmiri student I must have come across, says that although he believes in community demands being met democratically, looking at the reality of Kashmir, he sees no hope in democratic procedures taking place in Kashmir.

He ends our conversation by saying, “Till Kashmir issue is not resolved peacefully, I believe no community here can flourish properly. It’s the bitter truth we must face.”

It should be clear that without an inclusive, accommodating, and pluralistic society, a common, united, and strong regional identity will be hard, if not impossible, to maintain. Moreover, after everything is said and done, we cannot afford to fail each other as Kashmiris. Government or no government, we need to have each other’s backs for our survival as one people.

*The author would like to thank the resilient, ever brave, and caring members of the Kashmiri Sikh community for giving her the privilege of writing about them. The author hopes more voices from the Kashmiri Sikh community are given a platform to say and write their truth.