The Supreme Court is currently examining the constitutional validity of amendments made to the Waqf Act, and at the center of this legal storm lies an often-overlooked clause: ‘Waqf by User’.

The debate over this provision has become one of the most contentious points in court, raising fundamental questions about property rights, religious freedom, and legal documentation in India.

The issue gained prominence during recent hearings where senior advocates, including Kapil Sibal and Abhishek Manu Singhvi, strongly opposed the government’s decision to eliminate the clause from the amended Waqf law.

The matter was serious enough for Chief Justice of India Sanjiv Khanna to intervene and call for detailed, standalone arguments on the subject.

But what exactly is ‘Waqf by User’, and why has its deletion triggered such a sharp reaction from the legal fraternity?

What Is a Waqf?

To understand the controversy, it’s important to first understand what a waqf is. In Islamic law, a waqf refers to the permanent dedication of movable or immovable property—such as land, buildings, or even money—for religious, pious, or charitable purposes in the name of Allah. Once a property is declared as waqf, it becomes non-transferable and must be used only for the intended religious or charitable function.

Waqf properties often support mosques, dargahs, schools, orphanages, graveyards, and shelters for the poor. They are overseen by Waqf Boards established under the Waqf Act, which governs registration, management, and oversight of these properties.

Understanding ‘Waqf by User’

‘Waqf by User’ is a unique category of waqf that does not rely on formal written deeds or official registration. Instead, a property is treated as waqf based on long-standing public usage—typically for religious or community purposes—over an extended period of time, even if the original donor never officially registered it as waqf.

For example, if a parcel of land has functioned as a mosque or graveyard for generations, even in the absence of a deed or paperwork, it has historically been recognized by courts and Waqf Boards as a legitimate waqf through ‘user’.

This provision allowed local communities, especially in rural or under-documented regions, to preserve and continue using their religious properties without facing bureaucratic hurdles—especially in cases where written deeds had been lost to time or had never existed to begin with.

The Legal Dispute

During the hearings, Kapil Sibal argued that removing the ‘Waqf by User’ clause effectively invalidates thousands of such properties. “Suppose I own land and build an orphanage on it for public good—why should the government demand a deed to recognize it as waqf?” he asked, pointing to the deeply rooted social and religious traditions surrounding such dedications.

CJI Sanjiv Khanna expressed concern that the government had eliminated the concept altogether in the amended law. He acknowledged that while formal registration aids in maintaining proper records, many such properties have existed for centuries without documentation, and their users or caretakers are often in no position to produce legal deeds.

Justice S. V. N. Bhatti also weighed in, underscoring the importance of registration in curbing fraudulent claims. He emphasized that legal safeguards are crucial when it comes to declaring land as waqf, particularly in a country where land disputes are rampant. The state’s position, broadly, is that any claim to waqf status must be formally documented to be valid.

Sibal, however, countered by pointing out the practical realities. “How do you expect people to provide records that are 300 years old?” he said, highlighting how oral history, community practice, and continuous use have been the only “records” for many of these properties.

Why This Matters

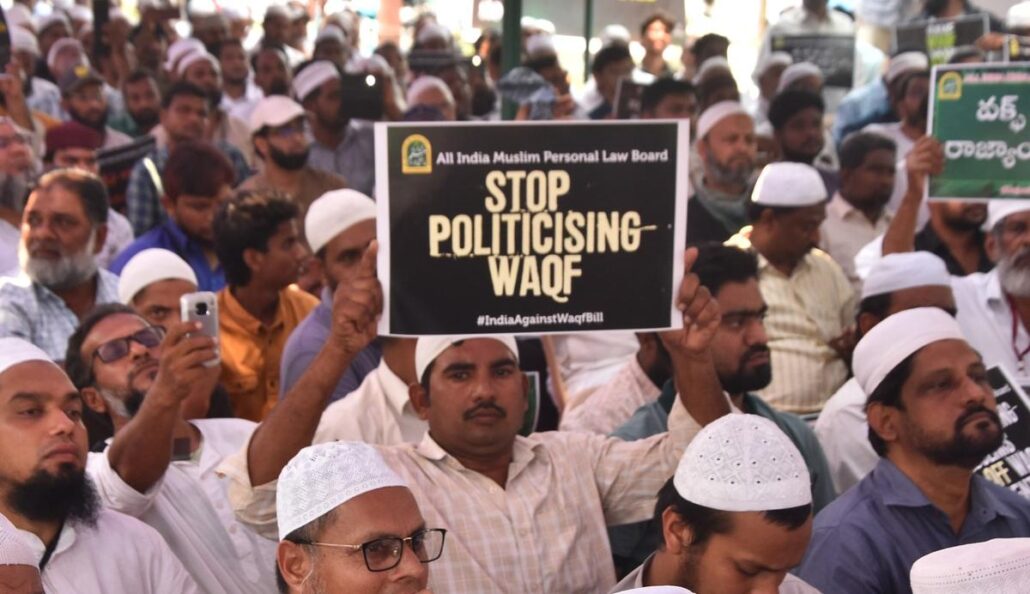

The government’s amendment, which removes the provision recognizing ‘Waqf by User’, could lead to the de-recognition of countless mosques, graveyards, and community spaces. Critics argue this amounts to cultural erasure and a direct attack on religious freedoms, especially for Muslim communities whose historical properties are often unregistered.

Supporters of the amendment, on the other hand, argue that the lack of documentation leaves the door open for land-grabbing, false claims, and administrative confusion. They insist that modernization of the waqf system—through mandatory registration—is long overdue.

The case, therefore, isn’t just about one legal clause—it’s about the collision between tradition and modern legal frameworks. Can centuries-old religious customs survive in a system that demands paperwork, notarization, and government oversight?

What’s Next?

The Supreme Court has now scheduled a dedicated session to hear arguments solely on the matter of ‘Waqf by User’. The government will present its side on Thursday, and the Court is expected to take a deep dive into the historical, legal, and constitutional dimensions of the issue.

With religious rights, property law, and social history at stake, this debate is likely to become one of the defining constitutional discussions of the year.