Khilat Abid/ Hooria Gillani/ Bayed Mubarak

In his autobiography, “Khar e Gulistan,” Maulana Abbas Ansari recalls that the unity of Kashmiri Muslims in the year of 1986 was like a “powerful force that arises from the coming together of people, similar to the force observed when scattered droplets combine to form the vastness of the ocean.”

This analogy highlights the unity of various social and religious entities that came under a single umbrella to form the Muslim United Front (MUF).

In the 70s and 80s, India adopted an aggressive birth control program. In 1977, approximately 24 percent of eligible couples in the age group of 15 to 44 years, capable of bearing children, were practising a form of birth control to escape government harassment. In Kashmir, this program had minimal impact. However, after Jagmohan was planted as the governor of the erstwhile state, most of the walls bore the advertisements asking people to practise birth control.

“By 1986, the family control program was openly endorsed and promoted in the Kashmir valley by the Jagmohan administration. I recall one of the initial meetings we organised on this issue in November 1985. We wrote around 72 letters and sent them to eminent members of the local community. This gathering held at Anantnag town was part of several meetings held in opposition to the family control program,” expressed Hamidullah Bhawani, a prominent leader associated with the Muslim United Front from the Dooru area of Anantnag district in south Kashmir.

“Earlier, in Kashmir, such moves did not make any impact, however, fears escalated as Jagmohan took several anti-Muslim measures. Several clerics were called by the administrator to actively campaign for birth control. It was at that moment in history that Qazi Nisar who had shot to fame earlier in 1985 after defying Governor’s ban over meat consumption, announced a reward for Muslim parents who bear two children or more,” Bhawani remembered.

Dr. Qazi Nisar attacked the government’s population control program, arguing that it was a “deep-rooted conspiracy to destroy the majority Muslim character of the state.” He said Muslims should not practise birth control, and he offered to reward Muslim parents who have more than two children with a cash prize of 21,000 rupees, or 1,600 dollars (Los Angeles Times, 19 October, 1986).

In the next few months, a union strengthened up with social, political and religious outfits, gathering under a single banner of Muslim United Front.

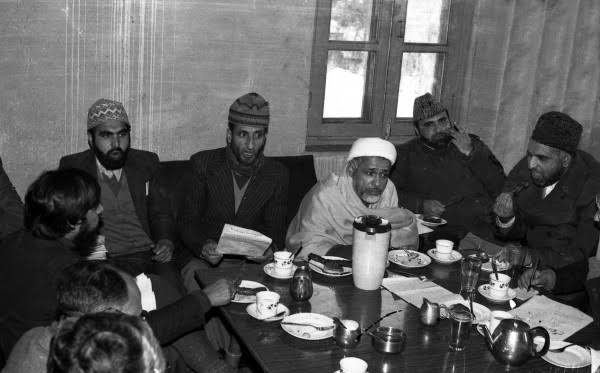

Referring to what he calls the ‘golden epoch’, Mir Muntazir Gull, the press secretary of Muslim United Front (MUF) and a close aide of Ghulam Qadir Wani, the general secretary of the organisation recalls, “It was not an easy time. The Muslim United Front gatherings were very chaotic at times. They got on the nerves of each other, but one principled stance of Muslim United Front was that the people of Kashmir are looking towards us and it was not that they wanted to suppress each other. The principle also was to take everyone’s opinion on board. It is one of the most exemplary times I have ever seen. We live in a time now when two people cannot agree with each other, even when they agree on most of the things. One single disagreement leads to massive fights, but here in Muslim United Front, so many contradicting opinions sat together and discussed, argued and yet reached a consensus or a common point of agreement.”

Gull, who is a prominent academic from the Aishmuqam area of Anantnag said that the meetings were not high-end elite gatherings. “Just a cup of tea or simple food would be more than enough for everyone,” he said.

Upon being asked how joining the MUF was, he said, “When new people came in, we read to them from the Quran and many other books and nobody had any disagreements. Muslim United Front was not merely a party, it was a resistance born out of constant State suppression of freedom of choice, expression and the right to have equal opportunities. We did not join Muslim United Front with the aim of joining electoral politics.”

In fact, Gull says, “I can speak for everyone who initially joined the amalgam. It was not about elections, it was about the idea of having a United Muslim Front, which has no parallel in human history.”

It is impossible to imagine a unity like that today. A Wahabi offering Namaz at a Hanafi mosque and likewise, a Hanafi stepping into a Wahabi mosque; Jamat-e-Islami going to Shia gatherings and Shias coming to Milad gatherings. It is almost impossible to even imagine anything like this would have happened in the past, Gull said.

The Dismissal of Employees

In 1986, the Muslims of Jammu Kashmir found themselves embroiled in a struggle for opportunities. Facing consistent discrimination in terms of employment. Their hard-earned positions were stripped away, their sacred places of worship were locked up, leaving them feeling marginalised.

At the centre of the turmoil was Jagmohan, the governor of Kashmir, who was determined to align the region’s political landscape with the interests of the central government, New Delhi.

Under his leadership, a systematic drive was launched to dismiss Kashmiris, particularly Kashmiri Muslims, from their departments. And replacing them were non-residents, further exacerbating the sense of alienation. Jagmohan was a part of the BJP and Shiv-Sena Political Party, and alongside him stood Hameed Ullah Khan and Ali Mohammed Watalli as ‘representatives’ who, ironically, were killing the interests of Kashmiris, Abbas Ansari states in “Khar e Gulistan.”

An estimated seven-hundred employees were terminated, who were mostly teachers from educational institutes. The series of employee suspension, however, began in consequence of the February 1986 Anantnag riots, when governor Jagmohan initiated an enquiry against top-rank officials and dismissed them for not “firing directly” at the protestors.

“A three-pronged attack against the authoritarianism of rulers in Kashmir” moulded itself. In the view of Professor Abdul Gani Bhat, “the launching of these fronts started with the dismissal of nine Muslim employees in 1986”.

The three fronts that were launched as a result were Muslim Students Front (MSF), the organisation of terminated employees, the Muslim Employees Front(MEF), and on a political level, the Muslim United Front (MUF). Professor Ghulam Rasool was appointed as the chairman of the Employees Front in Sopore.

This incident of employees being terminated triggered a series of protests in Anantnag.

Anger against Jagmohan

The anger against Jagmohan was not confined to the Muslim population. Prominent Dogra prince and the son of last Kashmiri emperor, Karan Singh characterised Jagmohan as “a bulldozer out of control,” attributing uncontrollable megalomania to him. Singh went on to assert that Jagmohan believed he could execute actions akin to the Turkman Gate incident in Jammu and evade consequences.

In 1986, a professional institute admissions list was declared, and only 23.6 percent selected were Muslim students, the rest 76.4 percent were non-Muslims. “The disparity was a result of Jagmohan’s rigid communal agenda,” Abbas Ansari writes.

Though meetings were being held across closed walls and a movement was shaping up, this selection list marked the beginning of street protests against the governor Jagmohan. In response to the biased admission list, a call for protest was issued by the Islamic Students League (ISL).

A protest march was taken out on August 20, 1986, at the Vishwabharati College, Rainawari in Srinagar. The police retaliated by opening fire, and five students were killed, Shafat Ahmad Chantsaz from Mallaratta, Srinagar being one of them.

The same day, female students protested in front of the Governor’s convoy passing through M.A. Road. Intense slogans were raised by students, who did not allow the convoy to pass. Shots were fired into the air and a few of the female students were injured, remembers Shakeel Ahmed Bakshi, of Islamic Students League.

Down south in Kashmir, the anger had been simmering against the Governor after he tried to enforce a ban on beef in the year 1985.

Rajiv-Farooq Accord

Sheikh Abdullah, throughout his life had resolved that he will not let anyone from New Delhi to come and rule Kashmir, but the announcement of Rajiv Gandhi’s support to Farooq Abdullah’s government in 1986 was seen by Kashmiris en-masse as a ‘deceit’ to Sheikh’s struggle by his own son.

“This triggered angry responses across the Kashmir valley. Though there were no visible indications of the same on the ground, an undercurrent was brewing up, and now people were looking for a change and desperately wanted to throw the National Conference (NC) off the power,” said Ghulam Rasool Shah, a former aide of Sheikh Abdullah.

But the anger against the accord was not confined to the general public. NC faced anger from within. “Realistically, we have to deal with the Congress. Look at history. They could make and break Sheikh Abdullah, Bakshi Ghulam Mohammed, G.M. Sadiq, G.M. Shah. And they toppled us once before. They are like a sword over our heads. History has reconciled us to accepting king-makers from outside,” Abdul Sanat Teli, former provincial chief of the NC, and an MLA from Srinagar told India Today in 1986.

The Muharram Procession of 1986

The first signs of anger against Jagmohan’s policies and Rajiv and Farooq’s close friendship first appeared in Srinagar in September 1986, when black and white posters surfaced across Kashmir, as much as conditions would permit. On the poster was a slogan, a date and a venue:

“Shia-Sunni Ittehad! Zindabad Zindabad!” (Shia-Sunni Unification! Long Live!)

Date: 13 September, 1986

Venue: Lal Chowk, Srinagar

These posters were distributed and pasted by young men and women to call for the entire Muslim population of Kashmir to participate in the Muharram procession on the eighth day of the holy month.

“The administration, led by Jagmohan, was certain that people would not show up for the Muharram procession. The admin was sure that no personality in MUF was capable of mobilising a crowd of even fifty people,” recalls Syed Sankar of Chattabal, Srinagar, a close aide of Moulana Abbas Ansari.

Muzaffar Rizvi, the former general secretary of Itehadul Muslimeen, the party founded by Moulana Abbas Ansari said, “On September 13, 1986, droves of people gathered around Lal Chowk, Srinagar. We do not know where these people were coming from. Women raised slogans of Shia-Sunni unification, and men filled the streets and marched to Lal Chowk wearing black dresses. All across Srinagar two important slogans were raised:

“O Hussain! O Hussain!

“Shia-Sunni Unification! Long Live! Long Live!”

From the day Maulana Abbas Ansari arrived in Kashmir from Iraq, he laid foundations for Itehadul Muslimeen, and throughout his life, made determined efforts to make headway in what he believed in. “By the time it was 1986, Ansari’s relations with Sunni scholars ran very deep. It was because of that, he frequently travelled to Anantnag to meet Sunni scholars to discuss thoroughly the unification of Muslims in Kashmir,” Syed Sankar said in an interview with The Kashmiriyat.

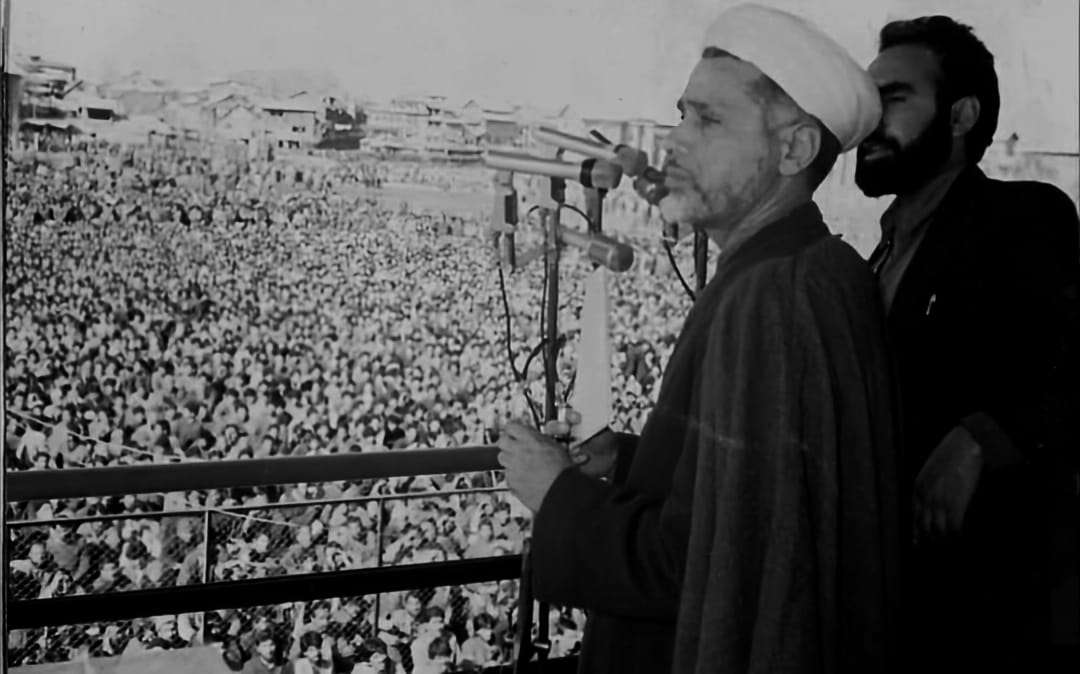

Moulana Masroor Ansari, who is now the chairman of the organisation, says that the procession started from Guru Bazar in Karan Nagar and from there took the route of Shaheed Gunj to reach Jahangir Chowk. They marched all the way through M.A. Road to Dalgate where the procession concluded.

People marched in thousands, estimated to be around half a lac people. “People boarded vehicles, and came from Anantnag, Ganderbal, Baramulla, Bandipora etc. and a multitude of people gathered at Srinagar’s Lal Chowk. The procession was successful, and the distinctions such as Firqas and Maslaqs faltered that day. All marched to Lal Chowk, where a stage was set up for renowned scholars to address the participants of the Muharram procession, and the feeling that loomed over was as if ‘a revolution had unfolded in Srinagar’s Lal Chowk’,” recalls Muzaffar.

The Election Debate

The series of meetings that began in Anantnag in 1985 spread to other parts of the valley and were being held directly under the banner of the Muslim United Front. “Election was never the agenda of Muslim United Front,” recalls Mir Muntazir Gull.

He said that it took most of us aback when Jamat-e-Islami proposed that Muslim United Front must contest the elections in the region being held in March, 1987. “Muslim United Front had a core of five members, so like everything important, the core members called in a meeting to decide whether to participate or boycott elections,” Gull recalls.

In this regard a meeting was held in Baramulla. The meeting lasted for a whole day and a whole night, and intense discussions took place between the five core members of MUF.

Hamidullah Bhawani spoke about the incident in detail. “The views shared in those discussions were conflicting. Four of the members were not in favour of participation in the election, however, the JeI was adamant that MUF should contest elections.”

Abbas Ansari, however, argues that some important members of the organisation (JeI), like Ashraf Saraf were against participation in elections. JeI insisted that if MUF decided against it, in that case, they (JeI) would independently contest the polls. The former chairman further states that Jamat had been “opposing” the core group and most of their decisions, inside the Muslim United Front and within its circles as well.

In the same meeting, JeI proposed that the core group of MUF should be expanded, with JeI in charge of the expansion process, to which all others agreed, says Gull. In this meeting in Baramulla, the members did not reach any resolution of the conflict, and therefore, they decided to discuss more pressing issues at hand.

This agreement may have been a result of JeI’s unparalleled financial power and the fact that MUF was using JeI’s Batmaloo office as their headquarters.

Maulana Abdul Ansari writes in his autobiography that the Baramulla meeting discussed that “the conflict of Kashmir” has not yet been resolved, so it was decided with a consensus that MUF will fight to resolve the “Kashmir issue.”

In another meeting, held at the former chief minister Ghulam Mohammad Shah’s residence, attended by Yasin Malik, Ashfaq Majeed and Hamid Sheikh among other members. The meeting had been called yet again for the same purpose as before; whether or not to contest elections.

The meeting, however, was interrupted when the police arrived at the scene. Many members, who were against the participation in elections, fled the scene. “Ashfaq, Yaseen, Hameed Sheikh among others escaped from the spot. Only a few were left, so the result turned in favour of those who wanted to contest elections,” said Shakeel Bakshi.

It is important to note here that the only members who voted for participation were JeI and its sister organisations, such as Tahafuz e Islamia, e.t.c. Most of these sister concerns joined MUF after the Baramulla meeting, where JeI had proposed the expansion of the core group.

Election Preparations

Farooq Abdullah challenged MUF to contest elections, in order to prove the workability of the Rajiv-Farooq accord. Interestingly, “Khar-e-Gulistan” offers insight into how certain members of MUF argued that they could not win the elections as “votes will be stolen.”

New Delhi would never let an organisation win that challenged the accession and stood for Kashmir’s self-determination, Hakeem Yaseen told the Muslim United Front leadership.

Through the electoral process MUF wanted to achieve two things; one is to enlighten people about the conflict of Kashmir and its impending irresolution and the second is to strengthen the sense of community among Kashmiri Muslims using MUF’s political ideology. On that pretext, MUF would also be able to tell people about their goals and purposes.

Shakeel Bakshi of the Islamic Students League says that the prominent faces of the organisations within MUF were asked to not nominate themselves as candidates. “It was decided through the course of several meetings that none of the representatives of any member organisation will contest in the elections, however, some members were adamant that they would themselves compete. A similar case arrived in Sopore. This was against the deliberations and mutual decisions passed by MUF,” Mir Muntazir Gull says.

MUF’s core group, which had now expanded to fifteen parties, decided that more than focusing on seeking votes, the leaders would rather focus on bringing to the forefront Kashmir’s status as a conflict zone and the people’s right to self-determination.

Due to MUF’s unwavering political stand with regards to the conflict of Kashmir and its right to self-determination, the Election Committee of India refused to identify MUF as a political party.

Hence, MUF contested elections through independent candidates. A green flag with a pen and an inkpot was chosen as the symbol for the party, which was later adopted by Mufti Sayed’s People’s Democratic Party (PDP).

This alliance between Farooq Abdullah and Rajiv Gandhi did not go well with Mufti Mohammed Sayed, another prominent leader from Anantnag. Maulana Abbas Ansari recalls in his autobiography that during the NC-Congress rallies, Mufti Syed used to flaunt the ‘pen’ or hold it in his hand to show dissidence against their alliance.

JeI tried to claim an upper hand in the electoral process, but were rebuked by other members of MUF. However, they did secure almost half of the forty-three (43) seats for themselves. Ummat-e-Islami and Tahafuz Islami Pulwama were given five seats. Bhawani says that there was a massive tussle on the Kokernag seat in Anantnag. “The Jamiat Ahli Hadees wanted the seat to be given to Haji Mohammed Abdullah, but Dr. Qazi Nisar wanted the seat to be contested by someone else. We filed five candidates and out of them, we won three; Mohammed Sayed Shah, Abdul Razaq Buchroo and Ghulam Nabi Sumji, though two of them changed sides later. But within the MUF records, they were contesting from Ummat-e-Islami ticket,” says Bhawani, who is also a leader of Ummat-e-Islami.

Seeing MUF gaining momentum, Ghulam Hassan Mir, Mohammad Yasin and Dilawar Mir were willing to join MUF, with the preconditions that the slogan of “Nizaam-e-Mustafa” be abolished and MUF should not challenge Kashmir’s accession to India, arguing that New Delhi would never let a party with such a manifesto make a government in Kashmir. MUF even had many non-Muslim leaders willing to join them, with the precondition that Muslim United Front remove the prefix of ‘Muslim’ from their name.

Observing that the Islamic Students League (ISL) had a strong cadre in Srinagar, MUF invited ISL to join them. MUF offered ISL five electoral seats, but they refused. The chairman of ISL, Shakeel Bakshi told The Kashmiriyat that, “I was lodged at Central Jail, Srinagar when I received a proposal from MUF to field ISL candidates on five seats of Srinagar. However, I rejected the proposal considering that we had joined MUF based on its principal agenda of not engaging in any political process which is against the basic essence of Islam. Also, I did not know under what circumstances MUF core had made this decision to contest elections because they were crystal clear earlier that they would not.”

While NC-Congress contested all seventy six assembly seats, out of which National Conference contested forty-five and Congress contested thirty-one, MUF contested only forty-three seats. But MUF candidates were steadfast, and carried out rallies in every town, tehsil and district, where people showed up in multitudes. HAJY Group and ISL vouched for MUF and “promised support and announced to campaign in six constituencies of Srinagar.”

All organisations within MUF believed in the self-determination of Kashmiris. “That scared not only pro-India parties in Kashmir but also their ‘masters’ in New Delhi. In response, D.I.G Ali Mohammad Watali, Divisional Commissioner Hamidullah Khan Banhali, Deputy Commissioner Srinagar Ghulam Qadir Pardesi and other government officials using state machinery did everything they could possibly do to help Farooq Abdullah succeed in the elections,” Ansari states.

The Curious Case of Lone and Shah

It was under Professor Abdul Gani Bhat’s leadership that MUF showed interest in inviting the People’s Conference (Abdul Gani Lone) and Awami National Conference (Ghulam Mohammad Shah) to be a part, while making them aware of MUF’s agenda. Both parties had earlier shown interest in joining hands with MUF.

The invitation to join MUF was extended to Abdul Gani Lone at Maulana Abbas Ansari’s residence in presence of Professor Bhat, who was certain that he would join as Lone himself seemed affirmative. Discussions were carried out, and he also participated in a rally organised by MUF in Chattabal, Srinagar but JeI rejected MUF’s merger with his party, arguing that People’s Conference had “secular” tendencies.

Interestingly, however, Lone had previously resigned as an assembly member and “in the way of construction of an Islamic identity had written a book to familiarise Kashmiris with it.”

At the same time, Ghulam Mohammad Shah, as a Chief Minister, felt that the future of Kashmiri Muslims was uncertain, especially after he was removed from his position in the ministry.

Ansari in his book states that Shah had also discussed the formation of Muslim Conference with Abbas Ansari; a reformation of his pre-existing party Awami National Conference. As per Ansari’s “Khar-e-Gulistan,” Shah wanted Muslims to be united under a single platform, but was himself reluctant to lay the founding stones. Shah in one of MUF’s rallies asked for people’s forgiveness for the mistakes he had committed in the past, while also claiming that his sympathies were with Pakistan.

Later, due to ideological differences with some members of MUF, both Abdul Gani Lone and Ghulam Mohammad Shah showed reluctance to join the Front. It was only after the elections, in the month of July, 1987 that both parties officially joined MUF.

Another point of discord between MUF and the two parties was the distribution of the mandate. The distribution of seats was extensively discussed with the two; MUF was willing to give Abdul Gani Lone two seats each in Baramulla and Kupwara. But Lone was adamant on the seat in Rafiabad, which JeI opposed vehemently. Ghulam Mohammad Shah, aside from seats in Amira Kadel, Nigeen, Zadibal and Ganderbal wanted to cooperate with right-wing Hindu parties in Jammu, which MUF rejected. “Shah was adamant on having the right-wing forces on our side in Jammu to defeat the Farooq-Rajiv coalition, but the Muslim United Front unanimously rejected the idea,” said Mir Muntazir Gull.

“Abdul Gani Lone promised that whichever assembly segment his party was not contesting, at that seat, People’s Conference, his party, would support MUF. He, in fact, encouraged people on Doordarshan and on Radio Kashmir along with his electoral rallies to vote for MUF,” Muntazir recalled.

Abbas Ansari says that it was after the results of the election were declared that MUF realised that by “not having a political alliance with Lone was a political blunder” and that “they could have dominated Kashmir” with that alliance, even if Lone won none of the seats he contested.

Iqbal Park Procession or ‘Kafan Bandh Rally’

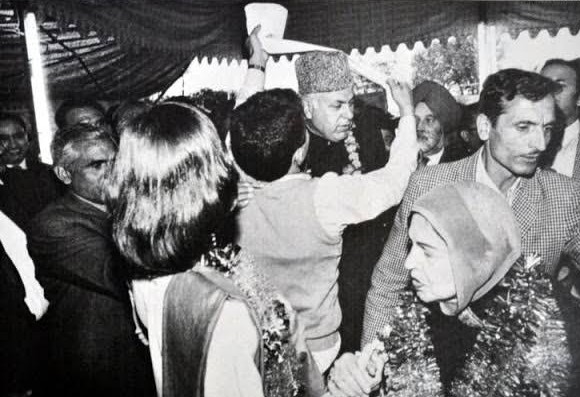

On September 6, 1986, the Muslim United Front (MUF) unveiled its constitution, dedicated to Shafat Ahmad Chantsaz, a boy who had been killed by the police on August 20 the same year. However, on the same day, its leaders travelling from Anantnag were arrested. Two days later, Muslim United Front issued a strike call against their arrests on September 9, coinciding with an India versus Australia match.

“We supported the MUF because they represented the sentiments of Kashmiris. The MUF was a strong movement; it was a wave and not something ordinary. People like me who were ordinary students, professionals and traders offered support to MUF during the election campaign. We were not at the centre of the politics, but were active supporters. We used to talk to people and try to convince them to vote for MUF. We helped in identifying people who could be suitable polling agents” Abdul Qadeer Dar, a polling agent for MUF in Baramulla district recalled.

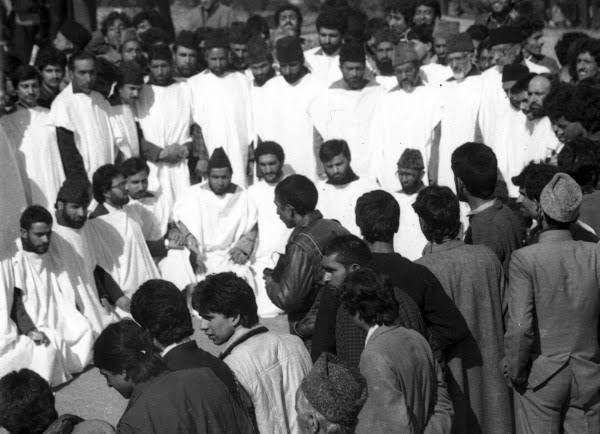

Before the election, MUF “decided to stage a unique and magnificent procession in Iqbal Park” to which everyone agreed. Professor Abdul Gani and Hakeem Ghulam Rasool were given the responsibility of the rally. The plan was to introduce the candidates for the forth-coming elections in coffins. On March 4, 1987 people in lacs visited Iqbal Park to participate in the procession, writes Moulana Abbas Ansari.

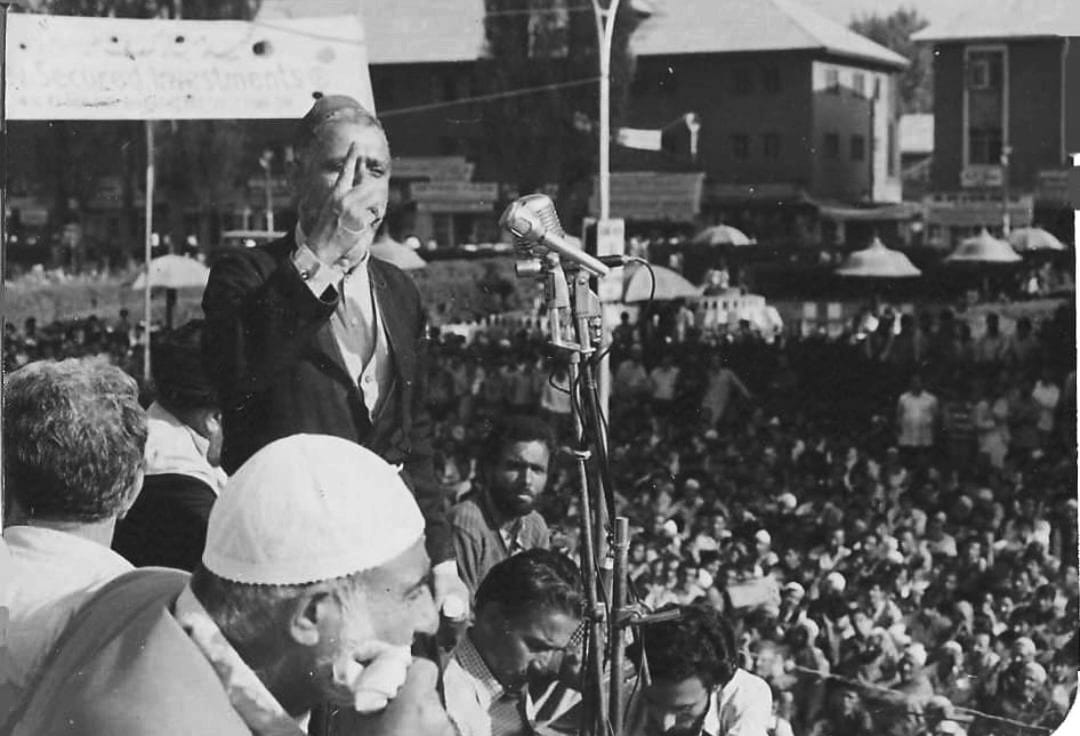

A grand stage was set for leaders at Lal Chowk in Srinagar, from where the leaders were flanked by the crowds to Iqbal Park. One of the most memorable parts of that day was the arrival of Qazi Nisar at Lal Chowk, recalls Javid Ahmed Hakak, an active campaigner of Muslim United Front from Soura, Srinagar.

Javid recalls that when Qazi Nisar arrived at Lal Chowk, a massive gathering followed him. It was the time when Ashfaq Majeed Wani raised the slogan:

“Zalzala hai Kufr ke aiwan mai! Lo Mujahid aa gaya maidan mai!”

(A quake has hit the halls of the Oppressor! Here comes the Warrior to the Battlefield!)

It was all too messy for all those sitting at the Jamat-e-Islami office in Batamaloo, Srinagar. “We drafted hundreds of letters, most of them to the preachers of mosques around Srinagar, Anantnag, and Kupwara, seeking their participation in the rally. Most of them did not respond to our repeated messages,” said Gull.

Bhawani recalls that there was a fear of police and MUF leaders were unsure if anyone would turn up for the grand day. “I was a student in Baramulla Degree College. Many of my friends and I were supporters of the MUF and we were often jailed for it. We were just small fries and not in the big league. Even for carrying out such trivial jobs in the MUF campaign, the police would nab and harass us. But this was not new. The police had harassed people long before the MUF arose,” recalls Abdul Qadeer Dar, in Ather Zia’s anthology “A Desolation Called Peace.”

It was proposed during a meeting, Bhawani recalls, that “MUF candidates in election fray would be introduced to the public wearing shrouds.”

A cavalcade of over 150 buses came from Anantnag with Dr. Qazi Nisar and another 70 vehicles with Moulana Abbas Ansari from Budgam. From Baramulla, another rally was led by Syed Ali Shah Geelani and other Jamat-e-Islami leaders. One of the rallies that joined the grand rally in Anantnag came from Dooru. Another cavalcade led by Hamidullah Rangrez of Churat, Qazigund joined the Anantnag rally at Khanabal.

The Iqbal Park procession marked the first instance since 1947 when Kashmiris assembled in large numbers to participate in electoral rallies. Residents from all corners of Kashmir gathered to witness the bodies of the candidates being carried in coffins. The chant of “Yahan kya chalega / Nizaam e Mustafa” echoed repeatedly.

According to Ansari, the extensive support for MUF stemmed from their focus on bringing the Kashmir issue to the assembly and asserting Kashmir’s right to self-determination, rather than emphasising developmental packages. In response to speeches delivered by MUF leaders at Iqbal Park, a case was filed against them at Shergarhi Police Station, situated near Iqbal Park, under the Terrorism Act.

“MUF was mainly relying on the oration skills and the fame of Dr. Qazi Nisar to gather crowds for them. He had campaigned for all the 43 candidates of Muslim United Front in their respective assembly segments,” said Gull.

He began his speech with a couplet of Iqbal:

“Ai aab-ruud-e-gangaa vo din hai yaad tujh ko / Utraa tire kinaare jab kaarvan hamaara”

(O stream of river Ganges, do you remember that day / When our Caravan descended upon your shores)

In the midst of the procession, two organisations found themselves in the middle of an internal disagreement, and they clashed due to their differences. But the organisations soon came to a reconciliation. But the newspapers and government organisations did their level best to use it as a point of contention against MUF, but in the end did not succeed.

Maulana Abbas Ansari draws a connection between the Iqbal Park procession and Farooq Abdullah’s visit to Delhi before the elections. He states, “A surprised and worried Farooq Abdullah rushed to Delhi in sheer hysteria, where he pleaded with Rajiv Gandhi and brought him to Kashmir, asking him to announce a one-thousand crore package in Sher-i-Kashmir Park in a futile attempt to quell the storm that had engulfed Kashmir.”

The Election Committee determined March 23, 1987, as the designated date for the elections.