In the heart of Srinagar’s bustling bazaar, an elderly man named Ghulam held court, his voice laden with the weight of decades marked by conflict. “In the days of the Dogra Maharajas,” Ghulam began, “there lived Yusuf, a humble farmer whose dreams extended beyond harvests to justice for those who nurtured the land.”

Yusuf, known for his devotion to family and the land, struggled under oppressive Dogra rule that denied him ancestral rights, reducing him and fellow farmers to tenants. Witnessing his labor enrich others while his family suffered fueled his resolve.

During a severe winter famine, Yusuf rallied farmers quietly, urging unity against injustice. Standing beneath a towering chinar tree, he declared, “We till this land with our sweat and blood, yet are denied our rights. It’s time to demand justice as rightful heirs!”

Yusuf’s impassioned plea ignited hope among farmers, resonating through the valley.

As Ghulam’s tale mingled with the bazaar’s rhythm, listeners were spellbound by echoes of Kashmir’s history—a land where reform and resilience defined its spirit. “And so, my children,” Ghulam concluded, “remember those who toiled for homes they were denied. And in this crowd emerged Sheikh Mohammed Abdullah, not as a ruler, but a brother among peasants, challenging the status quo. Theirs is Kashmir’s tale—a struggle where justice blossomed amidst Chillai Kalan’s cold.”

With Ghulam’s words lingering, the bazaar echoed with the enduring voices of Kashmir’s past.

The story begins during the mid-19th century, when Maharaja Gulab Singh solidified his rule over the Kashmir Valley through the Treaty of Amritsar in 1846, purchasing the region from the British for 75 lakh rupees.

This agreement marked the beginning of Dogra rule in Kashmir and established Gulab Singh as its sovereign ruler. Under his administration, Gulab Singh declared all land in the valley as his personal property, centralizing control and effectively making the state the ultimate owner of the land. Tej K. Tikoo in his book Kashmir: Its Aborigines and Their Exodus writes, “Maharaja Gulab Singh centralized control over land and declared all land in the Kashmir Valley as state property.”

This policy stripped local inhabitants of their traditional land rights, leading to widespread discontent among the peasantry. Alistair Lamb, in The Making of Modern Kashmir: Sheikh Abdullah and the Politics of the State, states that the Maharaja confiscated all private property rights in the Kashmir Valley and centralized them under the Dogra monarchy. This consolidation of land ownership marginalized local peasants and cemented the power of the Dogra elite.

This policy transformed local peasants, mainly Muslims, from traditional landholders into tenants who were obliged to pay taxes and rents to the state. According to Riyaz Ahmed Shah in The History of Muslims in Kashmir (1846-1947), Kashmiri Muslims faced systemic discrimination in land ownership and economic opportunities during the Dogra rule. They were often relegated to tenant farming and subjected to high rents and taxes, exacerbating their socio-economic plight.

Under the Dogra dynasty, the consolidation of land further entrenched a feudal land tenure system. Land ownership became concentrated among a privileged class of Dogras and Kashmiri Pandits who received grants known as Muafi lands. These grants, often exempt from taxes, were granted either for the lifetime of the grantee or in perpetuity, reinforcing the socio-economic dominance of the recipients.

The holders of these lands, known as Muafidars, wielded significant influence over the region’s social and political landscape.

Maharaja Ranbir Singh, Gulab Singh’s successor, continued this policy of land consolidation by allocating wastelands (chaks) to favored individuals, primarily Dogras and Pandits. This practice led to the emergence of a new landlord class called Chakdars, who enticed Muslim peasants to cultivate the land in exchange for paying specified land revenues.

This system perpetuated socio-economic inequality and cemented the power of the feudal elite, contributing to widespread discontent among the peasantry.

While the majority of Chakdars during the Dogra rule were reportedly Dogras and Kashmiri Pandits, there were instances where Muslims held positions as Chakdars. However, historical records indicate that these appointments were relatively rare compared to their Dogra and Kashmiri Pandit counterparts, reflecting the hierarchical nature of the land distribution system under the Dogra rulers.

The socio-economic structure and land distribution under Dogra rule were complex. Although Muslims participated in various roles within the agrarian system, their representation among privileged positions such as Chakdars was limited compared to other communities favored by the Dogra rulers.

From 1931 onwards, pressure mounted on Maharaja Hari Singh of Kashmir to address the grievances of the peasantry. Political entities such as the All India Congress, the Muslim League, and notably the Jammu Kashmir Muslim Conference (later renamed the National Conference), along with various peasant movements, voiced demands for immediate reforms.

In response, the Maharaja instituted several measures aimed at improving the agrarian sector. In 1933, he issued an order granting peasants proprietary rights over Khalsa land, marking a significant shift in land tenure policies since the inception of Dogra rule in 1846. Following the agitation of 1931, Mahraja brought in the Land Alienation Act of 1933, which restricted land sales to one-fourth of holdings for the first ten years, preventing the transfer of land from poorer peasants to wealthier individuals.

Further reforms included the Agriculturists Relief Act and the Right of Prior Purchase and Pre-Emption Act, which empowered peasants to challenge moneylenders in court over loan terms and restricted non-agriculturists from purchasing agricultural land, thereby protecting peasants from exploitation, however, despite these reforms, some entrenched features of the backward agrarian system persisted until the end of 1947.

Landlordism continued unabated, and the peasants working on the lands of Jagirdars, Chakdars, and Muafidars saw little improvement in their conditions. Despite significant reductions in land and other revenues, the peasantry generally remained impoverished, struggling to secure even two meals a day. Though the period witnessed growing social unrest and peasant movements demanding equitable land distribution and an end to exploitative practices, the landscape began to shift, as a mass leader was gaining ground in Kashmir right after the uprising of 1930s.

Throughout the 1930s and 1940s, Sheikh Abdullah vehemently criticized Maharaja Hari Singh’s policies of land consolidation and feudal exploitation in Kashmir. According to Balraj Puri, during the period from 1944-46, Sheikh Abdullah and his political organization, the All Jammu and Kashmir Muslim Conference (later renamed as the National Conference), intensified their opposition to the feudal land tenure system imposed by Maharaja Hari Singh.

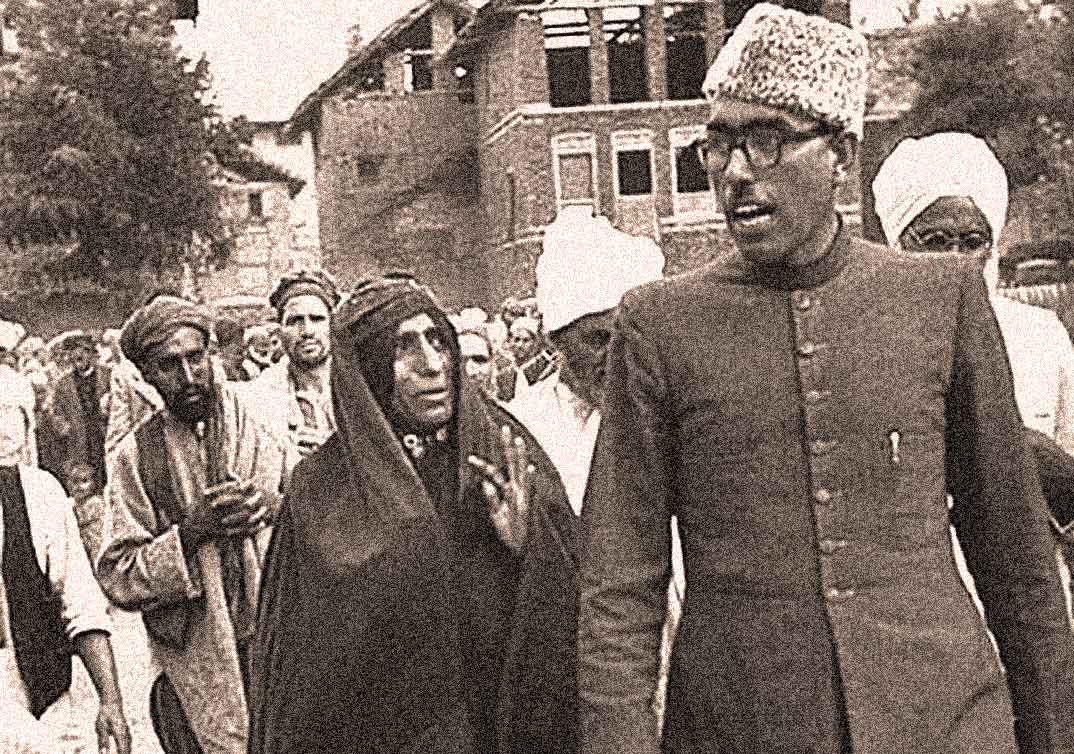

Sheikh Abdullah mobilized support among the Kashmiri Muslim population, highlighting grievances related to land ownership and economic disparities. Travelling from village to village, Sheikh Abdullah educated people on the necessity of agrarian reforms and socio-economic justice.

According to Tej K. Tikoo in Kashmir: Its Aborigines and Their Exodus, “Peasants mobilized against the feudal land tenure system, demanding land redistribution and fairer economic policies.”

The Kisan Tehreek, basked by Sheikh Abdullah, represented the aspirations of Kashmiri Muslim peasants, who organized protests and strikes against the feudal land system. Various historical texts and accounts, such as those by Tej K. Tikoo and Balraj Puri, discuss Sheikh Abdullah’s role in advocating for agrarian reforms that resonated with the goals of the Kisan Tehreek.

Sheikh Abdullah argued that these policies of land distribution marginalized the Kashmiri Muslim peasantry, reducing them to tenants on lands owned by Dogra and Pandit landlords. Abdullah’s critique was a central theme in his advocacy for agrarian reforms aimed at empowering the rural population.

After Sheikh Abdullah came to power in 1947 following Hari Singh’s signing of the treaty of accession with India, the war between India and Pakistan, and the constant political upheaval between the two countries delayed Sheikh’s first agenda.

Sheikh Muhammad Abdullah, did not believe in merely planning for change but acted swiftly to eradicate the exploitative practices allowed by the existing agrarian system. He took personal initiative in implementing the Big Landed Estate Abolition Act of 1950, educating cultivators about the government’s measures to grant them ownership of the lands they cultivated. In fact, Sheikh Abdullah personally oversaw the registration of tillers by special Tehsildars across the state, sharing in the joy of millions of peasants who found new hope and purpose.

Mirza Mohammad Afzal Beg, the Revenue Minister of the State, passionately advocated for economic equality, believing that every citizen had the right to benefit from their honest labor. He dedicated himself to explaining the reforms to the public and guiding revenue officers to ensure their prompt and accurate implementation.

Like Sheikh Abdullah, he believed that no reform could be too radical if it resulted in a content and prosperous rural population.

The Big Landed Estates Abolition Act of 1950 set a ceiling of 22.75 acres, with surplus land transferred to tillers without compensation. This landmark legislation led to the dissolution of 396 jagirs and the transfer of approximately 55 lakh kanals of land to 2 lakh and 50 thousand tillers. It marked the beginning of a series of reforms that liberated the peasantry from centuries-old oppression and ushered in a period of newfound prosperity.

This landmark legislation marked a turning point in Kashmir’s agrarian history, empowering the landless peasants and laying the foundation for more equitable land ownership patterns.

Critics, including leaders of the Kisan Mazdoor Conference (1945-1947), argued that the reforms were “inadequate and half-hearted.” They pointed out that the reforms primarily focused on Aabi lands (paddy lands), while large orchard estates and religious maufis (endowments) were exempted from the Abolition of Big Landed Estates Act.

Despite these criticisms, the reforms introduced by nationalist leadership were seen as a significant step towards alleviating poverty and empowering the rural population in Kashmir. The establishment of cooperative societies, reduction of land revenue, abolition of certain taxes, and provision of loans and agricultural inputs aimed at improving the socio-economic conditions of the peasantry.

These measures contributed to a sense of economic justice and led to improvements in agricultural productivity.