Qazi Shibli

Devastated by the shocking news of migration from her parents, Lalita Raina, known as Laleh, found herself reluctantly leaving behind everything she held dear. As a college-going young girl with predominantly Muslim friends, the prospect of bidding farewell to her life in the Kashmir valley weighed heavily on her.

In the early morning hours, Lalita’s family boarded a taxi, joining the caravan of hundreds of Kashmiri Pandits fleeing the region. Despite the heartbreak, Lalita, now 54, managed to pack a cherished photo from her recent trip to Pahalgam with college mates before departing for Jammu, carrying with her a symbolic pile of mud from her homeland.

Fast forward to the summer of 2011, Lalita reconnected with her Muslim friends, particularly her best friend Shayla (Name changed). The eagerness to find each other had only grown stronger over the years, transcending the miles they had moved in their lives and the responsibilities of motherhood.

Thousands of Kashmiri Pandits, who had spent significant parts of their lives in the valley, harbored a persistent desire to return to their homeland, where they had left behind homes and countless memories. Lalita fondly recalled growing up with Shayla in the streets of Anantnag, their families intertwined through their enduring friendship.

The narrative delved into the winter of 1989, a pivotal moment when Lalita was studying for her B.A Urdu exam at Shayla’s house. Ghulam Mohammed, Shayla’s father and a cleric, entered their room with an unusual silence.

This led Lalita to inquire about the sudden visit, uncovering the news of the shocking assassination of Prem Nath Bhatt, a prominent advocate, on December 27, 1989.

Prem Nath Bhatt’s writings, particularly an article in Martand on 17-3-1989, had highlighted attacks on minority shrines, including Gurtum Nag, a local Hindu temple claimed by Muslims in response to political plans. The aftermath of his death was catastrophic, with growing tensions preventing Shayla and Lalita from meeting as more Kashmiri Pandits fell victim to violence.

The situation escalated with the killing of ML Bhan on January 15, 1990, and the subsequent circulation of stories that fueled fear among the community. Threatening posters urging Pandits to leave Kashmir immediately appeared, and a blackout gripped the valley on the night of January 18-19, 1990. Inflammatory messages broadcasted through various means compelled Kashmiri Pandits to face a dire choice: leave, convert, or face dire consequences.

The absence of proper communication channels led to the rapid spread of rumors, intensifying the atmosphere of fear and uncertainty for the entire community.

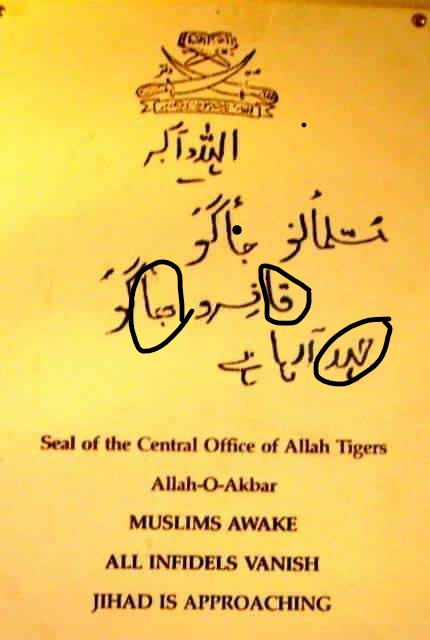

The stories of sloganeering from mosques in parts of Srinagar added with multiple rumours started doing rounds in the entire valley and the the threatening posters added to the fear. Shayla fought with her parents that the posters were a part of a propaganda asking them to stop Lalita’s family. The poster read, ‘Musalamano jaago, Kafiro baago, Jihad aa raha hai’– (Oh Muslims wake up, All infidels vanish, Jihad is vanishing). lalita said, “Papa, there is no ‘ق’ in a Kaafir, it is a ‘ک’, They could not even written Jihad properly, they missed an ‘ا’ also in Jihad,” Lalita had told her parents.

The Sufi factor

Hundreds of friendships and unnamed relations were lost. Many still try to find their old friends, neighbors over social media networking sites. Many Kashmiri Pandits google the images of their neighborhood or follow a journalist, an influencer, a boy, a girl from their locality, just to land into their inbox messaging them, “Can you please show, how my locality looks now?”. Kashmir is not a place, it is a feeling, I often say. No matter how far and how disconnected one is, Kashmir cannot escape from within you.

Amid the politics of decades on the issue of Kashmiri Pandit migration, a movie hit the theatres receiving a warm response from people. Genocidal slogans hate speeches were raised in several theatres and not anybody connected to the film came forward condemning these genocidal sloganeers.

The film in its climax also demonizes Sufi preachers who spread Islam in the Kashmir valley. However, the movie clearly as outlined by several prominent Pandit bodies said seems to be ‘distant from reality.’ In Kashmir, even today, hundreds of Hindus, Sikhs and people from other religions continue to visit the Sufi Khanqahs.

Afghans came to Kashmir in the 18th century. A funeral of a Kashmiri man was going by when the caravan of Kakkar Khan passed it. Kakkar asked the bearers to lower his palanquin as he wanted to know what it was.

The Afghan Governor lifted the shroud of the dead body lying in the coffin and later took out his dagger and cut off the ear and the nose of the corps. He announced, “He is called Charag Beg and the dead person should also tell the dead who Charag Beg is.” Following the incident, the name became symbolic of a curse that Kashmiris invariably utter to curse a person.

But long before the Afghans came, Buddhism arrived in the Kashmir valley from South India around 300 BCE and quickly spread throughout the region. Hinduism (in some form) had been the predominant religion followed by people in Kashmir. The caste system was an rampant aspect of Hinduism, notably in Kashmir and Buddhism advocated for a society that was less regimented and more egalitarian. One of the most plausible explanations for the religion’s rapid expansion in the Himalayan area is because of this fact.

Fa-Hsien traveled to Kashmir in 400 C.E, when the people’s language was Prakrit and Buddhism was thriving. When Sung-Yun returned 100 years later in 520 C.E., he saw a different picture: “the land had been decimated by Huns and was controlled by Lae-Lih, who did not follow the Buddha’s rules.”

In the mid-seventh century, the famous Chinese Buddhist scholar Hiuen Tsang traveled to Kashmir and found “more than one hundred Buddhist temples in the city of Srinagar alone.” Kashmir’s Brahmin rulers allowed the Buddhist monks to propagate their way of life in the region for nearly a thousand years. However, Buddhism had grown in popularity to the point that the Brahmins’ dominance saw it as a threat.

The emperors began oppressing the Buddhists, ushering in what has been termed as an era of Brahminic orthodoxy and revivalism in Kashmir’s history. “In 515 AD, Brahmins converted the Hun king, who then launched a wave of brutal devastation on Buddhist monasteries in Punjab and Kashmir. Crows and birds of prey would soar ahead, hungry for those within his army’s grasp. He boasted about being the thief who stole three crores of rupees. A century later, Buddhism in India, which had been powerful in the 7th century, was utterly eliminated,” Hieun Tsang.

It’s no surprise, when the first Muslim preachers (missionaries) arrived in Kashmir, many destitute lower-caste Hindus, as well as Buddhists, “converted to Islam in a torrent.”

Even though Umayyad Muslim soldiers had reached neighboring Afghanistan and Sindh in the early eighth century, help did not arrive quickly to those who felt oppressed under the Hindu monarchs. Durlabhaka-Pratapaditya II (d. 724) of the Karkota dynasty was the king of Kashmir at the time, and though his seat of power was in Kashmir, he reigned over a much greater empire. Kabul and Gandhar (the Jalalabad region now in Pakistan) were under his rule before he lost them to the Muslim conquest.

Conversations between various prominent citizens and Muslims from various areas of the world are well documented. In a letter to Abd Allah ibn Umar ibn Abd al-Azz of Mansura, a great monarch from the Karkota dynasty requested that he send an educated Muslim to Kashmir to explain Islamic law in the native vernacular.

The Hindu King of Kashmir had ordered the Quran to be translated into the indigenous Kashmiri language, according to Buzurg ibn Shahryar, a Persian Muslim traveller who published ‘The Wonders of India’ in the 9th century.

Raja Suha Dev was “a demon of a king” who devoured Kashmir for nineteen years, three months, and twenty-five days had given refuge and some land to the son of the Buddhist king of nearby Ladakh named Lha after his father had been killed in a battle, Jonaraja, a 15th-century Hindu historian, wrote.

Meanwhile, Shah Mir, a Hindu Rajput from modern-day Afghanistan, worked in Raja Suha Dev’s administration. Lha, a Buddhist, and Shah Mir, a Hindu later played a play pivotal role in the emergence of Islam to Kashmir.

Zulchu, a Mongol commander and a descendant of Genghis Khan invaded Kashmir in 1319 and spent eight months wreaking havoc on the region. Raja Suha Dev packed his belongings and escaped to Kishtwar, leaving his military commander-in-chief, Rawanchandra, in control of the situation.

Raja Suha Dev lost all respect and legitimacy in the eyes of his subjects as a result of this blunder. Many Kashmiris, like Lha and Shah Mir, fought heroically against the Mongols. After the Mongols withdrew and the smoke cleared, Lha emerged as a popular leader in Kashmir.

After centuries of Brahmin domination, Lha became the first Buddhist monarch of Kashmir in 1320, and Shah Mir became his commander. Shah Mir was a Hindu, but during Suha Dev’s rule, he would disguise himself as a Muslim and visit mosques. He was deeply moved by the lecture of a Sufi dervish from Kabul in Srinagar. He embraced Islam.

At the same time, Lha was agonized by the constant infighting between his Hindu and Buddhist subjects of Kashmir.

By the time of Bulbul Shah’s first visit, (13th century) the Brahmins’ rule over Kashmir was seriously in trouble. By the Bul Bul Shah returned, the Brahmin rule had completely collapsed, for the first time in history. On his second visit, Lha had a sudden encounter with Bul Bul Shah. Tazkira Awiya- one of the most authentic books on the origin of Islam in valley states, Bulbul Shah was offering the Fajr (dawn) prayer on the banks of the river Jhelum when he peeked out of a window in his palace one morning. He walked out to see this individual and afterward began learning about Islam from him.

Malik Sadr u Din was his new name after he embraced Islam under Bul Bul Shah Kashmir. He was influenced by Islamic practices that were “simple, free from useless ceremonies, caste and priesthood” (history records him more often as Lha or Rinchen Shah, after his original Buddhist name).

The first-ever Buddhist ruler of Kashmir now became the first-ever Muslim ruler of Kashmir, but the real transitional phase was yet to come.

In 1372 B.C., Syed Ali Hamdani arrived in Kashmir for the first time with the message of Islam and met professors and temple priests throughout his brief trip that lasted for nearly six months. During his visits, he was dismayed seeing the condition of Kashmiris, poor and oppressed by upper castes.

Upon his second visit in 1379, Syed Ali Hamdani brought with him 700 missionaries, who were highly qualified technicians, engineers, and architects from all over the world (Persia, China, Iraq, Egypt, Syria, and Russia). They taught Kashmiris architecture, agriculture, and other handicrafts, for which Kashmir has remained famous ever since. Among the skills taught by these missionaries were pashmina-sazi, Shawl making, calligraphy, carpet manufacture, Chinstitch, Paper-mache, wood carving, silver and copper wear and their carving, bookbinding, embroidery work among others.

Shah e Hamdan (as he is called in Kashmir) empowered individuals and emancipated the lower portions of the population from fear, uncertainty, ignorance, caste inequity, and poverty. Shah e Hamdan freed people of slavery of Kashmiri Pandits.

This freedom from the shackles of oppression from the upper classes was further taken into the nooks and corners of the valley by Sultan Zain ul Abideen through a local Sufi Saint- Makhdoom Sahab.

The distortion with Numbers

Nobody in Kashmir undermines the sufferings of Kashmiri Pandits. According to official figures, 219 pandits were killed in the valley before the migration of 1990. “More than 8,000 displaced people died prematurely during the first 10 years of displacement. The causes of death have been exposed to a hostile environment, snake bites, sunstrokes,” Seema Shekhawat writes in a paper on Conflict Induced Displacement in a journal on Conflict Trends in 2009.

The filmmakers say they have portrayed the plight of Kashmiri Pandits, however, several underlying connotations in the film, including the targeting of Sufi preachers, demonization of Kashmiri Muslims or anyone has ever opposed the polity of hate clearly is an indication that the film wants to deliver beyond what the filmmakers make public.

As widely discussed, the toll of casualties has been distorted heavily in the film- which seems to have become a biblical truth to a larger audience. The movie repeatedly emphasizes, “4,000 Kashmiri Pandits killed and five lakh displaced since the armed conflict began.” Official estimates state 219 Kashmiri Pandits were killed, however, let us agree, the official numbers are never in the game in Kashmir when it comes to the conflict stats.

The movie argues that around 3,50,000 Pandits left the valley, but several researchers have put the number around 1 Lakh 50 thousand. According to the Government data, a total of 64,827 migrants left the erstwhile state of Jammu Kashmir during the 1990s, as revealed in an RTI application filed by Pune-based RTI-activist, Prafful Sarda.

Kashmir Pandit Sangharsh Samiti, an organization of Kashmiri Pandits put the numbers at 399 killings. Panun Kashmir, arguably a right-wing Jammu-based organization of Kashmiri Pandits said that 1,341 Pandits were killed.

Land reforms in Kashmir- The Second Muslim empowerment

The movie has certainly made innumerable attempts to demonize everything that symbolizes the fight against any form of injustice. From Sufis to universities, Kashmiri Muslim leaders to professor, nobody has been spared- not even anything that contradicts the notion of ‘Nationalism’.

From 1846, Kashmir was ruled by the Dogras. Most of the landlords were either Dogras or Pandits under Dogra rule. Maharaja Gulab Singh had confiscated all private rights in land and declared all land of the Valley as his purchased property. The peasants were deprived of their occupancy rights over land. The Dogra Maharajas also bestowed the revenues of a portion of land to Kashmiri Pandits and their institutions. The rights were granted either for the lifetime of the grantee or in perpetuity. The Muafis (Category of the land granted to Kashmiri Pandits) reinforced their foothold on social and political landscape of Kashmir. This category of land was known as Maufi and the assignee was called Maufidar.

Throughout this era (1862), a new landlord class known as the Chakdars arose when Maharaja Ranbir Singh established a policy of allotting vast areas of waste land (chaks) to his favourites, who were mostly Dogras and Pandits. Since the Chakdars enticed Muslim peasants to till this land. The former had a solid position, and there was no need to evict them as long as they paid the specified land revenue. These Chaks were usually presented to the monarchs’ co-religionists.

Certain changes were made to the existential system after external pressure which included the demand by Indian National Congress, Muslim League. But the landlordism continued and the Muslim peasants working on the lands of Jagirdars, Chakdars and Muafidars hardly witnessed any positive change. As soon as Sheikh Abdullah was made the Prime minister of Kashmir in 1947, he did not want to wait for the agrarian changes. He waited for the ceasefire between India and Pakistan and by 1953, Sheikh Abdullah was the driving force behind the passage of the Big Landed Estate Abolition Act (1950), which gave tillers ownership of the fields they worked on.

The registration of tillers was observed by Sheikh personally. The Big Landed Estates Abolition Act of 1950 established a maximum of 22.75 acres for surplus land to be given to the tillers without compensation. About 55 lakh kanals of land were transferred to 2 lakh and 50 thousand tillers and thus the poor of Kashmir witnessed the second time empowerment after the initial empowerment by Syed Al Hamdani in the 15th century.

Hostile Muslim Neighbours

The film in a visible attempt to propagate some agenda has painted all Muslims of the Kashmir valley as hostile and seemingly supported the migration/ exodus of Kashmiri Pandits. This imagery seems to be distant from reality. It is tragic that Kashmiri pandits had to leave their abodes, but tragedies should not be painted to fit into an agenda.

Damji Raina was posted in Kashmir’s Pulwama when the Kashmiri pandits left the valley. When Damji reached home in the Anantnag district of South Kashmir, the mosque caretakers (Awqaf committee) came to him, pleaded not to leave, and promised full protection. He has been living unharmed in Kashmir till now.

Nothing has emerged abruptly, as portrayed. Kashmiri Muslims to date have vocally spoken against the migration of Kashmiri Pandits. In fact, several political leaders have been demanding from the Government of India to settle down the Kashmiri pandits. Farooq Abdullah cited today, “No Kashmiri Muslim was happy about the exodus of Kashmiri pandits.”

The film shows the Nadigram Massacre of 2003 happening in broad daylight, against the facts. When the massacre happened, it was the night of laylat ul Qadr and all the Muslims were busy praying the night-long prayers inside the mosque.

“When we were praying, we suddenly heard gunshots ring in the area. The Pandits were calling their Muslim neighbours for help. We ran out of the mosque leaving the prayers in the midst and saw a temple set ablaze. We then ran to the houses of Pandits, rushed them to the hospital in the dark of the night,” a local told The Kashmiriyat. He remembered the cordial bond Muslims and Hindus shared in this Central Kashmir area. “Even in their death, they called us,” he said.

The issue of Abrogation of Article 370

In a visible attempt to portray the abrogation of Articles 370 ad 35A, the foremost demand of Kashmiri Pandits, the movie fails to address the counter and the popular narrative among Kashmiri Pandits.

In July 2020, ‘Reconciliation, Relief and Rehabilitation’ stated that the abrogation of Article 370 was unjust and asked the government to restore the statehood and special status of Jammu Kashmir.

“We demand immediate restoration of statehood and special status to Jammu Kashmir. The Indian Constitution ensures the right to equality that extends to individuals, communities, religions, regions, and all social and political institutions,” said Satish Mahaldar, chairman of the Organisation.

He further stated that the right to equality ensures non-discrimination on the basis of religion, caste, region, or any other social and political sub-categories. Never before a state has been downgraded, “This is not done in a democracy. One can’t have a military solution to a political situation and can’t go to war with their own people,” he had said, adding, “The government needs to treat the people of Jammu Kashmir as their own” read the statement.

The Awaited return

Reminiscing her past spent in Kashmir, Lalita sees Shayla as an inseparable part of her existence. Shayla’s husband was killed in 1994. She had six young children to bring up, one of them was born five months after her husband was assassinated.

Shayla wants Lalita to return home. She has apologized several times for what the Kashmiri Pandits had to go through. The doors of Lalita’s house are locked. The doors and windows are decayed and the temple Lalita and Shayla had prayed was rusted until a few years ago. Locals repaired the temple from the mosque funds, though the story never made it out of Kashmir or even to Kashmir mainstream media outlets.

“It is not about Justice. Everyone in Kashmir has suffered immensely. It is not just any religious group. But Kashmir has suffered overall. The idea of Justice should not come from revenge. It is our Kashmir and the justice is that we find our homes, in security and in safety,” Lalita says.

Shayla grew up as a happy child in the care of both her (Muslim) and Lalita’s (Hindu) parents, the conflict later tore her life apart. She lost her young husband to the conflict. Her brother-in-law was killed during an encounter. Her children were targeted for their kinship and landed into jails, every now and then. Her life had a few moments to cherish- the most important ones with her friend Layla.

“My neighbours treated me like their own daughter. We had a society where every elder in the locality treated me like their own daughter. All the neigbourhood, Muslims and Hindus were on their toes, working during the festivities, marriages and during deaths,” Lalita remembered.

My sense of Justice is that I should be able to return home, Lalita stated.

Lalita and Shayla spent many moments of love, care and heartbreak together and yet today after 32 years have passed, the two cannot meet.