Javid Ahmed

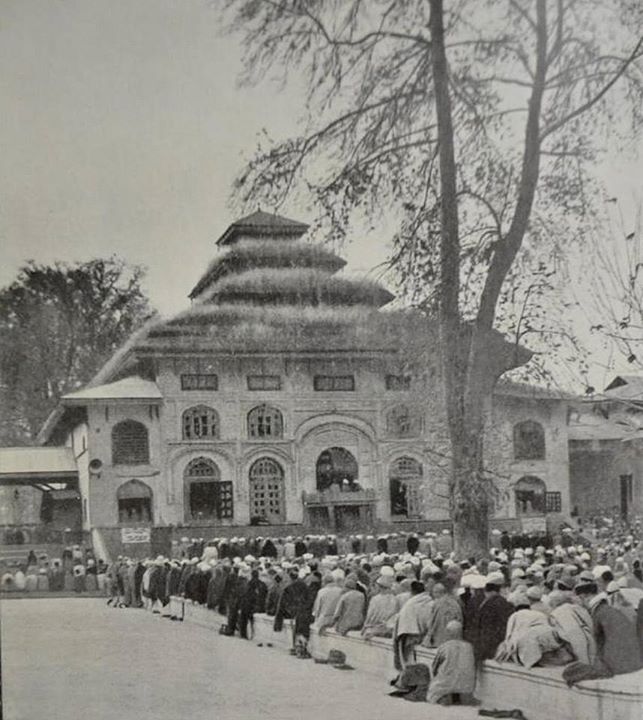

The story began with silent donations. Then, the heavy boots marched, first the Mughals, Afghans, Sikhs, and under the Dogras. Little changed. The state claimed Waqf land, meant for the poor and for prayer. There were no records, no protections. Just memories. And grief. But people remembered.

In whispers and sermons, they spoke of stolen land. In 1931, the pain turned into protest. This was not just about property. It was about power. About faith. Many Kashmiris rose from this storm and spoke of reform. Of reclaiming what was lost. They built walls, restored shrines, and named it the Muslim Auqaf Trust. But even this trust, over time, became a tool.

The story of waqf in Kashmir is not just about religion. It is about resistance. It is about how people fought to guard what was theirs—stone by stone, prayer by prayer.

At the very beginning of the Kashmir’s struggle against Dogras, Muslim leaders, while presenting their demands before the government, had strongly insisted that all mosques, Khanqahs and other properties, and lands be returned to them, over which Muslims had rightful claims, but which had been confiscated over the past century and a quarter, and upon which the government had established illegal control.

“This injustice began during the Sikh rule when Maharaja Ranjit Singh defeated the last Afghan governor of Kashmir, Jabbar Khan, near Shopian and took control of Kashmir. Initially, control was seized over Srinagar’s Jamia Masjid and the Khanqah-e-Moula, and at one point, it was even proposed that the building of the Khanqah-e-Moula be demolished,” Sheikh Abdullah has written in his autobiography Aatash e Chinar.

Sheikh throws detailed light on how Khanqahs and mosques were used for purposes other than religious. “Peer Ko, a village, and the mosque of Dara Shikoh were used as salt depots. Then, a mosque which the beautiful and intelligent queen Noor Jehan, wife of Jahangir, had resolved to build, continued to be used as a stable. Later, the Dogras turned it into the North Command’s storehouse. The mosque of Dara Shikoh, which Shah Jahan’s enlightened son had constructed on the advice of his spiritual guide Mullah Akhoon Shah, was later turned into an ammunition depot when his adversaries took control and pointed a cannon toward Bakhshi’s side.” (Aatash e Chinar)

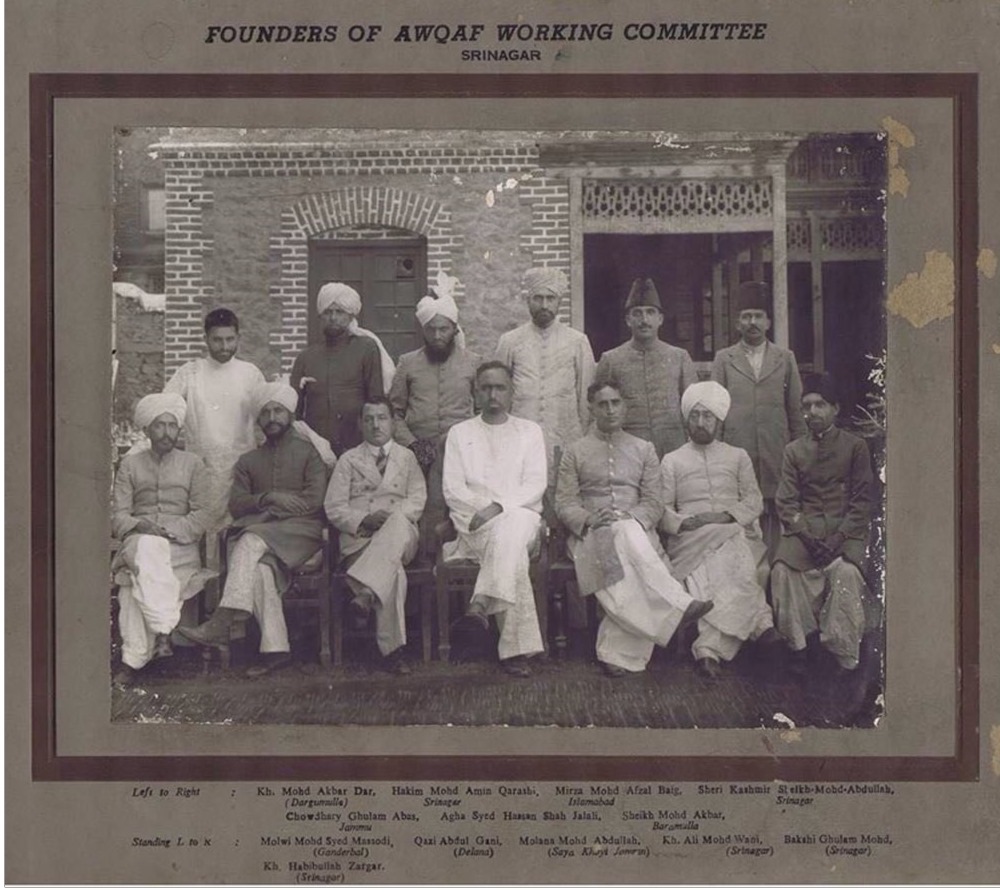

The situation in Jammu was no different. Many religious sites and properties remained under the control of the Dogra monarchs. When the Muslim Conference was formed in October 1932, it was decided that a Waqf Committee should be established to manage these properties.

Accordingly, the Auqaf-e-Islamiya (Islamic Endowment) was formed on 24 April 1940 to manage these properties. Sheikh Abdullah was appointed its president. While Sheikh mostly remained engaged in the political movement, he also began to pay attention to this significant community responsibility. After the Glancy Commission report (1931), some lands connected to the mosque of Dara Shikoh were given to the Auqaf, and they were subsequently converted into public gardens.

“The first work undertaken by the Trust was the observation of Eid Milad un Nabi in Srinagar,” Writes MY Saraf.

Following this, Sheikh Abdullah faced anger from within his party, most prominent being Prem Nath Bazaz, as he writes in Aatash e Chinar. The members accused Sheikh of being an “Islamic extremist” merely for commemorating Sheikh Mohammed Abdullah.

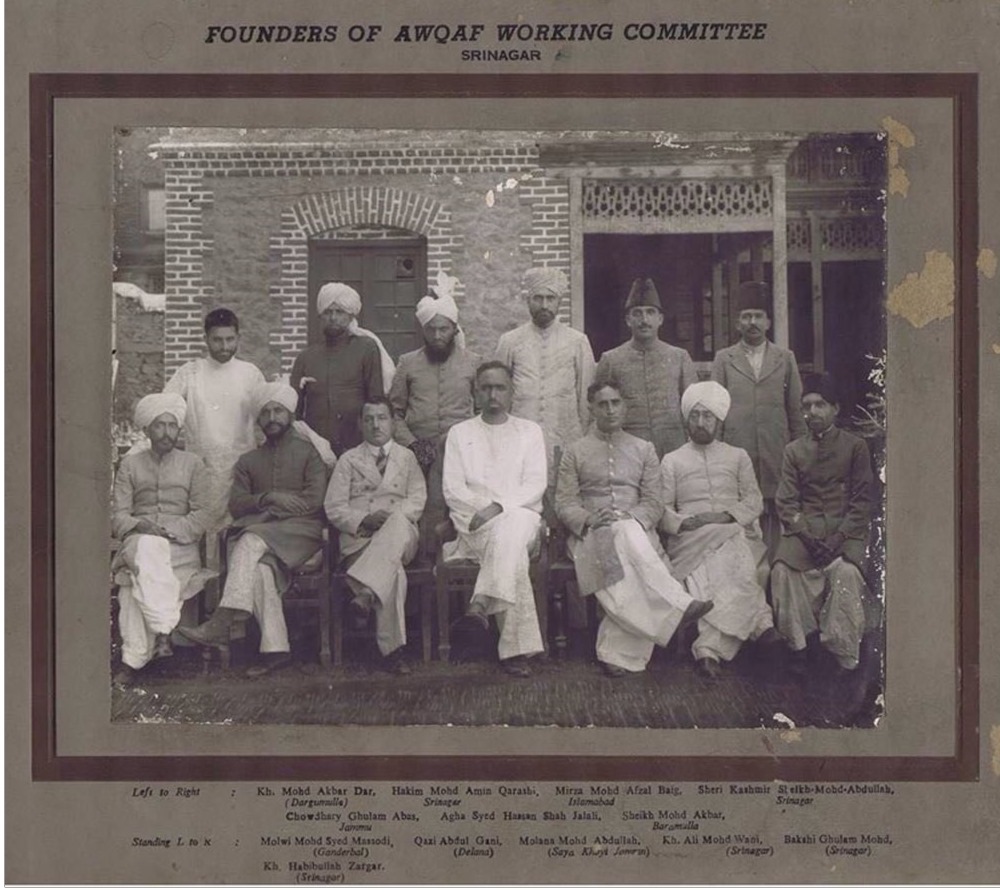

Following the protests of 1931, the Muslim community demanded that the Glancy Commission, appointed by the British to enquire into the “misrule” in Kashmir, that “Along with other discrimination which Muslims faced under Dogra rule, the horrible among them was converting Masjid into godowns. Without caring for the religious susceptibilities of the Muslims, the government confiscated many religious places of Muslims like Khanqah-e, Maula, Khanqah-e-Bulbul Shah, Khanqah-i-Dare Shikoh, Madine Sahab, Pather Masjid (Srinagar), Malashahi Bagh Mosque (Ganderbel), Khanqah-i-Safi Shah (Jammu), Bahu-Mosque (Jammu), and Eid gah Srinagar.”

“Restoration of religious buildings: Some mosques in the state had been retained by the state and put to secular uses, because the government officials did not have any consideration for the susceptibilities of the Muslims. But the Commission restored these buildings to the Muslims,” the Commission recommended in 1932.

With the report, Muslim properties were slowly returned to Auqaf. The mosque built by Sultan Zain-ul-Abidin’s elder brother, Ali Shah, still stands as a testimony to its antiquity. Auqaf soon took control of the Eidgah Srinagar, cleaned and took control of its management. In the early days of its operations, Auqaf cleared a wooden shed constructed on the land adjacent to the Pathar Masjid (Stone Mosque). A litho press was also purchased, upon which “Haqeeqat” and “Sadaqat” were printed. The first editor of the newspaper “Khidmat” was Maulana Muhammad Saeed Suri.

The Muslim Auqaf Trust also started loan services to Kashmiri Muslims without any interest. “My father took a loan from the Muslim Auqaf Trust in the 1960s when we were constructing our house in Soura. Several Kashmiris were granted loans, mostly against gold,” said Mohammed Akbar of Srinagar, who was a beneficiary of the loan service.

Education loans were also granted to the destitute and poorer sections of society. Thousands of students benefited from the scheme.

The Hazratbal story

Historically, the management of religious endowments (waqf) in Kashmir was decentralized. Khanqahs, mosques, and associated properties were overseen by hereditary custodians (mutawallis), with informal structures deeply embedded in Sufi traditions. Khanqahs such as Khanqah-e-Moula (built in the 14th century), Makhdoom Sahib, and Charar-e-Sharif were maintained by the descendants of saints or caretakers appointed by local Muslim communities.

However, during Dogra rule (1846–1947), the state began to exert more control over religious institutions. The Maharaja’s administration intervened in waqf affairs, especially in high-revenue shrines. The Muslim community increasingly viewed these interventions as encroachments. Post 1932, the formal registration of the properties of Waqf began. Sheikh advocated for a unified waqf structure by the mid-1940s. According to M.Y. Taing’s biography, Sheikh Abdullah: A Biography, and Tareekh-i-Hurriyat-e-Kashmir, Sheikh proposed a people-centric endowment body to run Khanqahs, schools, and hospitals.

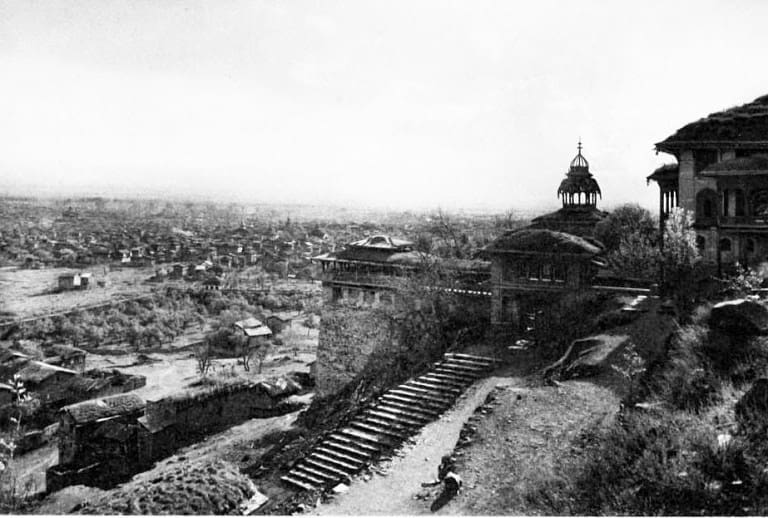

By the early 1950s, plans for establishing the Muslim Auqaf Trust (MAT) were underway, but political upheavals—including the Sheikh’s dismissal and arrest in August 1953—delayed formal establishment of the Trust. The Trust was eventually institutionalized in 1960–61, even as Sheikh remained in jail under the Kashmir Conspiracy Case. Once operational, the MAT began acquiring custodianship of major shrines. One of its most significant projects undertaken was the reconstruction of the Hazratbal shrine, a brainchild of Sheikh Muhammad Abdullah.

The idea of reconstructing the Dargah emerged to Sheikh during a meeting with Habibur Rahman, who was the Government of India’s head of construction in 1967. He writes in Aatash e Chinar, however, the only constraint was money, as all the land donated to the Dargah was consolidated by the Auqaf. In his autobiography, Sheikh says that he began neighborhood visits to collect cash and in-kind donations from the public. “Donations were collected and, praise be to God, this campaign continued righteously. People from Srinagar and beyond contributed generously. Most of this amount was collected by me from pilgrims at Hazratbal and devotees in towns and villages in the form of donations and offerings, and in 1979, the elegant and soulful view of the Aasar-e-Sharif began to adorn the skyline of Srinagar.” (Aatash e Chinar)

A refined type of stone was imported from the same mines that once supplied white marble for the Taj Mahal.

The design was completed by Hyderabad’s renowned architect Fayyazuddin. This design is the first clear and authentic example of classical Islamic architecture in Kashmir. Before this, the Khanqahs and mosques of Kashmir often reflected influences of Buddhist and Tibetan architecture, such as Pagodas, which are still common in Bhutan. Compared to them, the new design of the Dargah was entirely made of wood, except for the intricately carved walnut wood interior.

For pilgrims, sitting arrangements, facilities for ablution, bathing, and prayer were provided. There is no doubt that the new building of the shrine brought a revolutionary transformation in the identity of Kashmiri Islam. Its construction took considerable time and effort, but the outcome was breathtaking. Over one crore rupees were spent on its completion. The calligraphy in the central chamber housing the relic of the Prophet (Mooy-e-Mubarak) evoked the memory of classic Islamic calligraphy. The imam, in those days, stayed somewhere near the current Gulshan area. The calligraphy of the Arabic verses was done by top calligraphers from Lahore and Delhi. An exquisite chandelier was imported from Czechoslovakia, the largest and finest of its kind in Kashmir.

However, the project drew sharp criticism. Publications such as the RSS’s Organizer and right-leaning Indian political leaders accused Sheikh of fostering a “Muslim Vatican” in Srinagar. In his jail writings (preserved in the Selected Works of Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah), he wrote about his desire to create a spiritual and educational hub that could serve the people.

Following the Indira-Sheikh Accord of 1975, Sheikh returned as Chief Minister. He reasserted control over the MAT, expanded its reach, and undertook reforms. In the following years, the trust expanded control to over 1,200 properties, including shops, orchards, and agricultural land. The Trust Invested in hospitals (like Gousia Hospital), schools (e.g., Islamia High School), and libraries. As of 2025, the number of Waqf properties in the state stood at 32, 533.

However, internal dissent emerged. Urdu newspapers such as Srinagar Times (1977), run by Janata Party leader Ghulam Muhammad Sufi, reported nepotism, revenue mismanagement, and political patronage complaints. The Vice Chairman of Mirza Kamal u Din, former Municipal Secretary, however, accused the Srinagar Times editor of blackmailing him. “He wanted a route through a hotel of the Auqaf building in Boulevard Srinagar, but he was not given any land,” Abdul Rashid Sahaf said in one of his interviews.

As per the latest data collected by The Kashmiriyat from Waqf officials, 60 Madrassas spread in every nook and corner of the valley are being run by Waqf. 3500 students are being taught in these institutes. Waqf is running five prominent Darul Ulooms: Jamia Madinatul-Uloom Hazratbal, Dar-ul-Uloom Aishmuqam, Anantnag. Dar-ul-Uloom Qaimoh, Anantnag, Dar-ul-Uloom Watlab, Sopore, and Dar-ul-Uloom Aham-i-Sharief Bandipora.

The Waqf runs 3 Nursing and Medical Technology colleges: Bibi Halima College of Nursing & Medical Technology in Srinagar, Alamdar College for Nursing & Medical Technology in Charari-Sharief, and Syed Mantaqui College for Nursing and Medical Technology in Awantipora. In addition, it operates 3 Higher Secondary Schools, namely Sultan-ul-Arifeen Wakf Higher Secondary School in Srinagar, Mantaqui Memorial Wakf Higher Secondary School in Awantipora, and Hanfia Islamia Wakf Higher Secondary Institute in Anantnag. The Waqf also manages 5 High and Secondary Schools, 4 Middle Schools, and 1 Primary School, serving students across various districts including Srinagar, Pulwama, Bandipora, Sopore, Anantnag, and Tangmarg.

Auqaf becomes Waqf Board

In 2003, during his tenure as the Chief Minister of Jammu and Kashmir, Mufti Mohammad Sayeed initiated the reconstitution of the Jammu Kashmir Muslim Auqaf Trust into what became known as the Jammu and Kashmir Waqf Board. This was done through a government order issued by the then PDP-Congress coalition government, which dissolved the existing Waqf Board structure and established a new trust model for managing religious endowments and properties in the region.

The trust was registered under the Jammu and Kashmir Trusts Act, 1978, and the official notification led to the formation of the J&K Waqf Trust with Mufti Mohammad Sayeed as the chairman. This shift effectively placed the management of all major Khanqahs, associated assets, and institutions directly under the control of a government-nominated body, instead of an autonomous Waqf Board.

This represented a clear increase in government control over Waqf affairs, as the restructured body was led by the Chief Minister and included trustees appointed by the General Administration Department (GAD) of the state government. The previous system, which had elements of community participation and relative institutional independence, was replaced with a trust model rooted in state authority.

The trust was tasked with managing hundreds of religious sites and endowments, including prominent Khanqahs such as Dargah Hazratbal (Srinagar), Charar-e-Sharief, Makhdoom Sahib, and Baba Reshi. It also oversaw the functioning of educational and healthcare institutions funded by Waqf revenues. The total revenue from shrine donations and Waqf assets during this period was reported to be several crores annually, with Hazratbal Shrine alone contributing a significant share.

The first official meeting of the restructured Waqf Trust was held on August 2, 2003, where trustees were appointed, including senior government officials, select religious scholars, and administrative representatives. The nomination process, managed by the GAD, emphasized state involvement at all levels. This marked a departure from the earlier Waqf Board functioning, where appointments and operations featured broader community representation and relatively more autonomy from the state government.

The watershed moment for the MAT came post the abrogation of Article 370 on 5 August 2019. The Central Waqf Act, 1995, was extended to Jammu and Kashmir. The Waqf Board was reorganized under the Ministry of Minority Affairs. In 2022, Dr. Darakhshan Andrabi was appointed Chairperson. A digital inventory was initiated, recording 32,186 kanals of waqf land (J-K Govt. Minority Affairs Report, 2023).

Following this restructuring, one of the most significant and controversial changes was the removal of traditional caretakers, or mutawallis, who had managed shrines and mosques for generations. These individuals or families were often locally appointed and held deep communal and spiritual ties to the places they oversaw.

Union Minister for Parliamentary Affairs and Minority Affairs, Kiren Rijiju, commended Dr. Syed Darakhshan Andrabi, Chairperson of the Jammu Kashmir Waqf Board, for her efforts in transforming Sufi Khanqahs in the region. During his visit to Dargah Hazratbal on February 15, 2025, Rijiju stated, “Dr. Andrabi has transformed the Sufi Khanqahs in J&K, and the development done by the Board under the leadership of Dr. Andrabi can be the role model for all shrines throughout India.

The latest Waqf Amendment Bill aims to abolish “waqf by user”—a traditional principle where properties, used continuously for religious or charitable purposes over centuries (even without formal documentation), are recognized as Waqf. This change threatens to strip legal protection from such undocumented but historically significant Muslim endowments.

At least 50% of Waqf land in Kashmir lacks formal deeds, relying instead on “waqf by user” protections. According to research, about 20,000 families in Kashmir depend on Waqf assets for their livelihoods—farmers using Waqf land, shopkeepers near religious sites, and staff in Waqf-funded schools, orphanages, and charities.

Though the exact impact of the Waqf Amendment Act remains to be seen, the developments around the Waqf Act have stirred important questions about heritage, representation, and institutional balance. As efforts toward transparency and reform unfold, it will be crucial to ensure that such measures do not come at the cost of erasing long-standing traditions or unsettling community trust.

In regions like Kashmir, where religious institutions serve not just spiritual roles but social and economic ones as well, any policy shift must be approached with sensitivity, equity, and a deep awareness of the histories they are set to influence.

The Author is a historian from Srinagar. Witness to several political and religious developments in Kashmir, the author has decades of expertise in writing on historical subjects.