In a discovery that could bring scientists closer to understanding how life might form beyond Earth, researchers from NASA and Germany have suggested that Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, may naturally produce tiny bubble-like structures similar to cells. These structures, called vesicles, could form in Titan’s cold, methane-rich lakes and may help support the kind of chemical reactions needed for life.

The study was published on July 10 in the International Journal of Astrobiology. Scientists involved in the research say these vesicles might emerge from a unique interaction of special molecules on Titan’s surface. These molecules, called amphiphiles, have two sides, one that mixes well with methane and another that avoids it. When these molecules interact with droplets formed during methane rainstorms, they could create double-layered shells, very much like the outer walls of living cells on Earth.

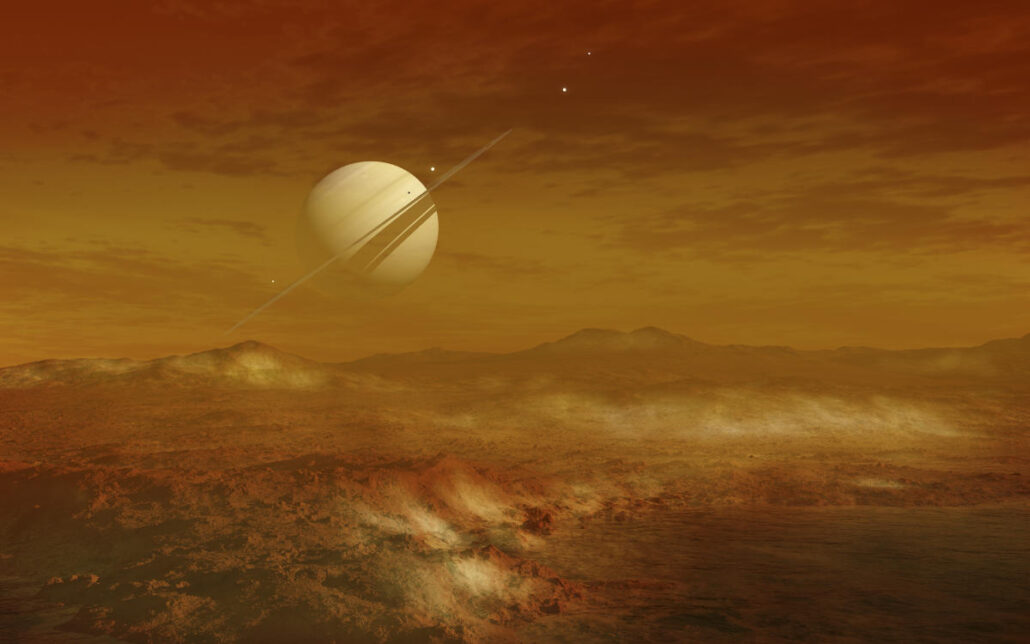

Titan is a very different world compared to Earth. It has freezing temperatures, a thick atmosphere filled with nitrogen and methane, and large lakes of liquid methane and ethane instead of water. But despite its harsh conditions, researchers believe it could still host the building blocks of life, just in a different form.

Christian Mayer from the University of Duisburg-Essen in Germany and Conor Nixon of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center were part of the team behind the study. According to Nixon, the discovery of such vesicles on Titan would be a big step forward. “The existence of any vesicles on Titan would demonstrate an increase in order and complexity, which are conditions necessary for the origin of life,” he said.

The process, as the scientists describe, is simple but powerful. When strong methane winds and rains create tiny droplets that splash into Titan’s lakes, those droplets could collect amphiphile molecules around them. These molecules would then form protective shells, similar to what we see in early cell structures on Earth, known as protocells.

The research is based on computer models and lab simulations, not direct observations from Titan itself. Still, it offers a strong case for how life-like structures might form even in environments that seem completely alien.

Titan has long fascinated scientists because it is the only other place in our solar system known to have stable liquids on its surface. NASA plans to send a spacecraft called Dragonfly to Titan in 2028, which is expected to arrive there in 2034. While it won’t directly explore the lakes, Dragonfly will study the surface and atmosphere, looking for signs of complex organic molecules.