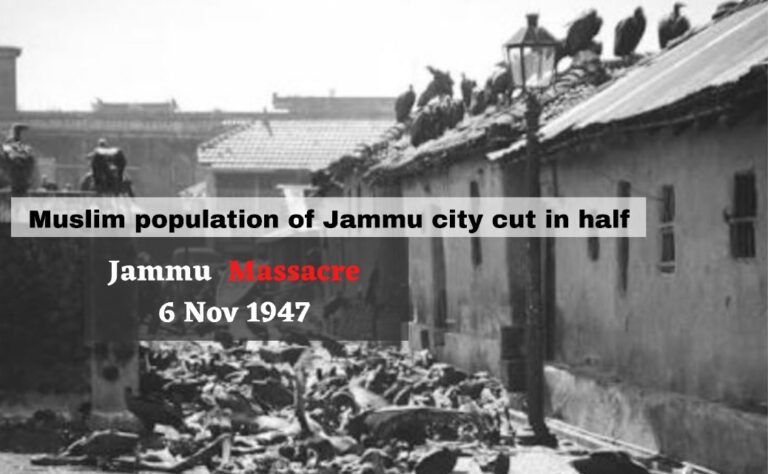

The Jammu Massacre, in the aftermath of partition of India and Pakistan, is one of the most gruesome episode of human history. In this long piece, we explore the incidents of the day through prominent historian M.Y. Saraf’s book.

Following the March 1947 rioting in Punjab Rawalpindi, Attock, Murree, Bannu, and Hazara, the first trickle of refugees arrived in Jammu in April. The daily flood peaked in late 1947, when an estimated 160,000 Hindus and Sikhs came from Pakistan’s western provinces. (January 26, 1947, The Times, London)

During the partition-related unrest, the majority of Sialkot’s non-Muslim population had fled to Jammu. Sialkot and Jammu were essentially twin cities. The Dogras were the primary people of Sialkot’s north-eastern region. They were culturally and linguistically tied to the Hindu Dogras of Gurdaspur on one side and Jammu on the other. As the Punjab border award was announced and the unrest escalated, over 100,000 Sialkot residents fled to Jammu. (Islamabad’s Ministry of Refugees and Rehabilitation).

By mid-September, they reached 65,000 in Jammu alone. When they arrived, the communal strain reached “the breaking point.” They brought horrifying stories of “Muslim atrocities” with them, which were recounted in the press and given official credence by the state media. For example, a Jammu-based Hindu paper claimed that “a Dogra can murder at least two hundred Muslims,” demonstrating the communal depths to which the media and political parties had descended. (J. K. Rady, ‘Massacres of Muslims in Jammu Province,’ Nawa-i-Waqt (Lahore), October 29, 1947.)

This exacerbated the Muslim massacres and migration. Almost immediately, angry Dogra refugees, aided by relatives from Jammu, began a general purge of the Muslim community. State officials provided them with weapons and ammo. Non-Muslim deserters from the Sialkot Unit who had moved to Jammu and had brought guns and ammo with them now used them. (Punjab Police Abstract of Intelligence, week ending August 31, 1947, p. 612)

In late October 1947, an ominous wave of violence began sweeping across Jammu, setting the stage for one of the darkest chapters in its history. The city, once bustling with the coexistence of various communities, was now gripped with fear and uncertainty. Muslims, particularly those in positions of authority, found themselves targeted first.

Muslim officers in the police force were systematically removed or confined, prominent historian M.Y. Saraf writes.

Among them were Syed Sultan Ali Shah, Sheikh Fazal Alam, and Mian Said Ali, all of whom were held in police lines under suspicion. “We were officers of the state, sworn to protect law and order, but suddenly we were the ones under lock and key,” recalled one Muslim officer who managed to escape to Pakistan later.

Simultaneously, a “proclamation ordered Muslims to surrender any arms” they held for personal defense. Despite Muslims gathering in a meeting and affirming their loyalty to the Maharaja, the violence showed no signs of abating. As the days passed, disarmament left the Muslim population increasingly vulnerable.

One of the first major atrocities occurred at the Khanqah of Baba Jeevan Shah, a revered Sufi Khanqah in Jammu where 200 Muslims—men, women, and children—sought refuge, hoping the sanctity of the place would offer them protection. But they were sorely mistaken. Mobs, emboldened by the Maharaja, descended upon the shrine, massacring everyone inside.

“No one survived. My brother, my mother, they were all butchered,” said a survivor whose family had taken refuge there, her voice shaking as she recalled the horror.

To make an explicit assessment of Jammu’s Muslim massacre by the State-sponsored attempt to shift demographics in 1947, it is required to examine the region’s population composition at the time. According to the 1941 Census, the eastern half of Jammu province was inhabited by 619,000 non-Muslims, including 10,000 Sikhs and 305,000 martial Dogras Rajputs and Brahmins, and 411,000 Muslims.

To the north and astride the Chenab, Muslims made up 40% of the population and were in the majority in Riasi, Ramban, and Kishtwar, and had nearly reached parity in Bhaderwah. The situation of the majority of Muslims and Hindus inside the province explains in part their divergent goals for the state’s future. At the same time, it featured aspects of Leo Kuper’s posited fragmented and insecure society, which were liable to explode into ‘genocidal violence’ during a crisis, 137 Hutchison and D. Smith, ‘Genocide in the Plural Society,’ L. Leo.

It is vital to note that the majority of Jammu province’s Muslim population was Punjabi-speaking.

The Muslims of western Jammu have long-standing topographical, historic, economic, ethnic, and cultural relations with the cities and towns of West Punjab. They were adamant about joining Pakistan.

The Stories of Massacre

Dogra Hindus were a minority in Jammu province overall, but they were a majority in its eastern districts such as Udhampur, Kathua, and the Chenani Jagir. Seventy-five percent of the Hindus in Jammu lived in these four districts, which were adjacent to Hindu-majority areas in Punjab, such as Gurdaspur, which was annexed into India in 1947.

The bulk of Muslims in Jammu province lived in the western districts of Mirpur, Reasi, and Poonch Jagir, which were next to Punjab towns and cities. Their proximity to Punjab was essential because it let refugees travel easily into and out of Jammu province during partition.

Thousands were slain and hundreds of thousands fled to the border cities of Sialkot, Gujrat, and Jhelum. The extent of the devastation was highest in Jammu, where Muslims were in the minority. They focused on Ustad da Mohalla, Pathan da Mohalla, and Khalka Mohalla. The last was significantly greater than the first two combined. By mid-September 1947, these Muslim communities were a sight of devastation. Hundreds of members of the Gujjar and Bakerwal community were killed in Ram Nagar mohalla. The village of Raipur, located within the Jammu cantonment region, was destroyed by fire.

According to the Pakistan Times (Lahore), the Muslim population of Jammu city had been cut in half by mid-September.

It was only after months of migration on November 5th, 1947, an announcement was made that Muslims would be “safely” transported to Pakistan.

Trusting the promise of safety, hundreds of Muslim families gathered at the police lines in Jammu, desperate to escape the escalating violence.

Around noon, 36 trucks arrived, and as many as 60 people were crammed into each vehicle. What they thought was a ride to safety soon turned into a journey of terror.

At Satwari Cantonment, one of the witnesses, the Second Master of Samba High School, recalled the scene: “We saw Hindus and Sikhs armed with guns, swords, and spears lining both sides of the road. Fear spread through the trucks like wildfire. Some young men jumped out in a desperate bid to escape, but they were killed on the spot.”

Hundreds of thousands of Kashmiri refugees have gathered in the border cities of Sialkot, Gujrat, and Jhelum by late November. Dogra state troops were at the forefront of Muslim attacks. The state authorities were also said to be arming not only local volunteer organisations like the RSS, but also those in neighbouring East Punjab areas like Gurdaspur.

As the convoy neared Samba, the trucks were diverted away from the road leading to Pakistan. Panic set in among the passengers as they realized something was terribly wrong.

“The driver said the usual route was closed and we were being taken via a safer road, but there was no safety in their words. It felt like we were being led to slaughter,” said another survivor. Soon enough, the trucks were stopped, and the true horror unfolded. Armed militias surrounded the convoy, separating men from women.

“They first took the women,” a survivor recounted with tears in his eyes. “I watched as they dragged my sister away. I couldn’t save her. They were ruthless, laughing as they stole our lives.”

Those who tried to resist were hacked down in cold blood. In one instance, a newlywed couple was torn apart—when the groom attempted to hold onto his bride, a Sikh man severed his arm with a single blow of the sword.

In a statement published in the daily Nawa-i-Waqt, G. K. Reddy, an editor of the Kashmir Times, said, ‘I observed the armed mob slaughtering the Muslims savagely with the complicity of Dogra troops.’ State authorities were openly distributing guns to the mob.’

Not only had the state administration demobilized a huge number of Muslim troops serving in the state army but Muslim police officers whose loyalty had been questioned had also been sent home. In Jammu, the Muslim garrison was disarmed, and the Brigadier Khoda Box of the Jammu cantonment was replaced with a Hindu Dogra commander.

According to reports, the Maharaja of Patiala was not only supplying weaponry but also operating a Sikh Brigade of Patiala State troops in Jammu Kashmir.

On November 28, Dogra troops evicted the entire Muslim inhabitants of Dulat Chak, alleging it was a part of the state. The Dogra army assaulted the adjacent villages, forcing the Muslims to flee beyond the old Ujh river bed. (FIR no. 179, Sialkot District Police Record, Thana Shakargarh, 28 November 1947).

Among the survivors was Ghulam Mustafa, an MLA whose wife, son, and sister were all killed in the attack. His daughter, however, was abducted.

“They took her away in front of my eyes. I couldn’t save her,” he said, choking back sobs, as quoted by newspapers of the time- M.Y Saraf.

His daughter’s ordeal, however, did not end there. After years of searching, Sheikh Muhammad Abdullah personally intervened, and she was finally rescued and returned from India to Pakistan.

On November 6, another convoy of about 25 trucks, this time filled with Muslim elites and educated individuals, including gazetted officers, set off. Among them was Dr. Abdul Karim, who survived to tell the harrowing tale. The trucks, like the previous day, were diverted, but this time towards the Jammu canal.

As they reached a secluded area, the trucks were surrounded by armed Hindu mobs. “We were trapped, completely encircled by men with spears and swords. I watched in horror as my family was butchered one by one. My daughter was dragged away; I tried to protect her, but I was struck down with a sword, and I lost consciousness,” Dr. Abdul Karim recounted, his voice trembling with the weight of the memories. Twenty-six members of his family were killed that day.

“It was a slaughterhouse,” he added. “We were helpless, slaughtered like animals.”

Despite the overwhelming odds, some Muslims tried to fight back. Havildar Abdullah, a soldier, stood firm as an attacker attempted to drag away his newlywed wife. Refusing to let go, Abdullah was hacked to death in front of her. His wife’s screams were lost amidst the chaos of swords, bullets, and bloodshed.

Yet some survivors managed to escape the killing fields.

“I put off my shoes and ran barefoot, zigzagging through the chaos as they fired at us. Somehow, I made it to the border, where the call of the Adhan reached my ears. That was when I knew I had reached safety,” said one of the few who survived by hiding in an abandoned kiln overnight.

The few survivors who made it to Pakistan were a shadow of their former selves, with stories that would haunt them for generations. Only 900 Muslims from the original convoys reached Sialkot alive, their faces marked with the trauma of the massacres they had witnessed.

The world outside remained largely unaware of the extent of the atrocities.

“Justice Kanwar Dalip Singh, the agent of the Indian government, told us bluntly that we must leave for Pakistan. ‘Your safety cannot be guaranteed here,’ he said,” recounted one Muslim leader who had tried to negotiate a peaceful solution.

This massacre remains a chapter of Jammu’s history that is seldom discussed in mainstream narratives.

Survivors like Dr. Abdul Karim and the families of the lost still bear the scars of that time. The recounting of these stories, filled with personal testimonies and vivid memories, serve as a haunting reminder of the depths of human brutality, but also the resilience of those who survived.

As Dr. Abdul Karim, who later set up a practice in Sialkot, remarked in his final words on the massacre, “We were betrayed, butchered, and forgotten. But we will never forget.”

Mass Abduction of Women

It goes without saying that thousands of Muslim women were abducted from various parts of Jammu province, especially in the districts of Jammu, Kathua, Reasi, and Udhampur. On the higher side, their number is estimated at twenty-five thousand, but that, in Saraf’s opinion, is a “liberal estimate”.

Among the girls abducted was also the minor daughter of Chaudhri Hameedullah Khan, who remained untraced. The fate meted out to Muslim women may be judged from the following account given by an abductee. The pattern was the same everywhere.

“I was married to Sultan Ali in the month of Har last. After a sojourn of about five or six days at my parental home, my husband returned to his village Nikkian Akalian in tehsil Akhnoor, Jammu State. After about six months of my wedding, a few days before Id-uz-Zuha (25-10-1947) the State Dogra troops and Hindu Chib Rajputs armed with rifles, swords, and spears attacked our village, killing about 600 men, women, and children. Some of the inhabitants made good their escape to various villages in Pakistan. My parents and brothers were all killed. My cousin Mst. Rehmat, daughter of Bagga, and I were captured by the hooligans and marched to village Chhamb, whence we were confined in the house of Mehr Din, a Lohar. We found 18 other girls already confined there. The house was under military guard. Mehr Din had strict instructions not to let any girl out of the house, failing which he and his family were threatened with extinction. He was promised that expenses incurred by him for the maintenance of the girls would be paid by the State. Mehr Din had a young daughter named Aisha and, being desperate to preserve her virtue and the lives of his family, he danced to the tune of the Dogra soldiers. On the night following the 8th day of our confinement there, a Dogra Subedar named Amru arrived in the company of 20 other Dogras. It was a moonlit night. Amru had us brought in the open and asked his companions to select a girl apiece. Every one of them got hold of a girl of his fancy. I was taken away by a Dogra named Gian. Mehr Din was a silent spectator to this distribution and did not utter a word for fear of his own daughter and family. Gian raped me and kept me in his house for 22 days. My refusal to submit to his carnal desires was punished with a severe beating. He had a mother and six brothers of whom Daya Ram’s wife kept a watch over me. Every morning Gian and his brothers used to go out with a Jatha for the murder of Muslims and plunder and used to return by dusk with a booty of clothes, ornaments, utensils, etc., and related their horrible doings of the day to instill terror into my heart…”

“… They also boasted of having attacked villages Mattianwala, Dakhuna, and Najjan in Pakistan territory. For the first two days of my captivity in Gian’s house, I refused food and water but then, for fear of his thrashings, I started eating. I was made to drink water with cupped hands and food was also placed on my hands. Gian was constantly bullying me to become a convert to Hinduism but I persistently refused. Gian and his two brothers, Daya Ram and Munshi, possessed rifles and the other three were armed with spears, etc. After about a month of my captivity, the Pathans attacked Deva Batala, causing the inhabitants of Chhamb to evacuate to Jaurian and the next day to Akhnoor. After a three-day halt, we crossed the Akhnoor bridge and stayed there for four days on the outskirts of the town. Mehr Din and his family were also there. The 20 girls were not allowed to meet, but I did sometimes catch a glimpse of my cousin Mst. Rehmat. Then we moved to Jammu where Muslims of other villages had taken refuge. After four days, the refugees were ordered to return to their respective villages. The inhabitants of Chhamb took the route via Bern and Panitoot and after a halt of about four days at each place reached Sarkampore where the stay was extended to three months. At Panjtoot, as a result of consultation between themselves, Gian and his brothers agreed that Chhamb being not safe till then, it was advisable to take up temporary quarters at Planwala, a sizable village.”

“On the 22nd of October, a large number of Muslims were able to escape from the area where the notorious Bahu fort is situated. The military opened fire, resulting in certain deaths. However, some Muslims succeeded in entering Jammu city and went straight to Mian Abdur Rashid, the Senior Superintendent of Police, requesting him for protection against military encirclement. He deputed Raja Sohbat Ali Khan, Sub Inspector Police, and a resident of Bhimber for necessary help but as soon as he reached the spot, he was subjected to a barrage of fire. A bullet struck his eye, two entered his right thigh and left leg; he fell down and died instantaneously. His corpse was stripped of the uniform and three of his fingers were cut off to easily remove the gold rings he wore. After great difficulty, Mian Said Ali succeeded in getting his dead body for a burial. On the 23rd of October, Thakar Natha Singh, Sub Inspector of police who was a friend of Raja Sohbat Ali, was killed by the Sanghis because he had the courage to condemn them not only for the dastardly murder of his friend but also for killing innocent Muslims. On the same day, Mian Abdur Rashid was put under arrest. The Bakr Eid fell on the 25th of October. The Hindu-Sikh goondas had been active since the 19th of October and by that time, several Muslims had been killed and a number of women abducted. On the morning of Eid, one Atta Muhammad, a Mistri by profession and a resident of Mohalla Mastgarh, Jammu city, convinced that Hindu goondas were determined to carry off his three daughters, aged 19, 16, and 14 years, himself killed them to protect their honour.”

Kathua and Samba

After August 14th, the number of non-Muslim refugees entering Jammu increased dramatically. A committee responsible for arranging their stay was led by Pandit Prem Nath Dogra, a retired SDM, who would later play a key role in the unfolding events.

Harassment of Muslims, particularly in border areas, began around this time, leading to the migration of 2,000 Muslims to Sialkot by October 10th. The border had been sealed, and no Muslim was permitted to leave the state.

Brigadier Collier, an English officer commanding the Sialkot sector, attempted to visit Jammu to check on the conditions of Muslims in the area, but Brigadier Rawat, his counterpart in Jammu, refused the request.

Inside Jammu city, training centers for Hindus to learn the use of firearms were set up in Vaid Mandir, Raghu Nath Mandir, Talab Rani, Pacca Danga, and Gurdawara Pacci Dhakki, all overseen by retired military officers.

Despite the growing tension, there were still Hindus like Bankay Behari, Nand Lal Pawa, Chattru Das, and Dr. Sethi who warned their Muslim friends, including Ch. Allah Ditta and Dr. Abdul Karim, of the dire situation that was developing.

Muslims in the border areas of Samba and Kathua became the first victims of the violence. As a coordinated strategy, villages near the border were surrounded, and indiscriminate firing ensued, terrifying Muslim inhabitants and forcing them to flee towards Jammu city.

The primary goal was to eliminate the younger members of the community, with women often being abducted and property looted, remember the survivors.

As Muslims fled, they were killed, plundered, and abducted at multiple points along the way.

Dr. Abdul Karim recorded a particularly chilling incident at Deva Vatala, where Maharaja Hari Singh personally initiated the massacre.

According to Karim’s note, the Maharaja shot three Gujjars near Misriwala Bridge. One eyewitness, Akbar Ali Haidri, recounted:

“The Maharaja pulled out his revolver and shot at the Gujjars. Two of them fell down while the third one tried to run away but was shot in the back. The party then drove away towards Vatala.”

The brutality didn’t stop there. Bodies littered the roads and paths leading to Jammu city, so much so that a passerby told Dr. Abdul Karim that he had seen a small child suckling at the breast of his dead mother near the Tawi river.

The mother’s body, stripped naked, had been lying there for days. Muslims from certain areas of Jammu, like Mohalla Ustad and surrounding villages, were fortunate enough to survive the onslaught, thanks to the efforts of Col. Pir Muhammad Khan, a Muslim Conference leader who later became a Minister in Sheikh Abdullah’s first cabinet. However, the rest of the city was not so lucky.

Dogra and Patiala soldiers set up posts in strategic locations around the city, including the Residency Road, tehsil buildings, Dhakki Qabristan, Urdu Bazar, and houses in Mohalla Mastgarh. Any Muslim who ventured outside the refugee camps was swiftly killed.

The ring around the Muslim population tightened day by day, creating panic among those trapped inside. Despite the overwhelming odds, a few leaders organized what resistance they could. Capt. Mian Nasir-ud-Din and Ch. Mohammad Sharif (Beichawala) helped distribute the few available weapons, including muzzle-loading guns, rifles, spearheads, and axes, to able-bodied men.

They divided themselves into groups, led by individuals like Muhammad Amin, Abdul Majid, and Fazal Rahman, trying to defend the Muslims as best they could.

On November 1st or 2nd, the military attacked a house where 300 Muslim refugees had sought shelter. All the male refugees were killed, except one man who was wounded, and the women were abducted. Within days, entire Muslim areas of the city, including Mohallas Dal Pattian, Mastgarh, Talab Khatikan, and Bazar Qasaban, were emptied of Muslims.

Another significant attack had occurred on October 14th, when mobs targeted villages in the police jurisdiction of Bishna, district Jammu.

They killed several Muslims and looted their property before setting the villages on fire. Mian Said Ali, a District Inspector of Police, arrested 30 looters and recovered stolen property, but his efforts were in vain. The violence continued, and Said Ali later learned that two-thirds of the Muslims who had sought refuge at the police station had been killed.

In the days following, a series of massacres unfolded across Jammu and Kathua. Muslim convoys fleeing towards the Pakistan border were ambushed by Dogra soldiers and armed mobs.

On October 23rd, Dogra soldiers opened fire on a large crowd of Muslims in Miran Sahib, Jammu, killing many. Maharaja Hari Singh personally supervised the genocide in some areas.

At Rajpura, a convoy of Muslim refugees was forced to pass through a mob of armed Hindus. According to witnesses, quoted by Saraf, the mob attacked the refugees at the order of the officers present, resulting in a massacre.

In Samba town, around 10,000 Muslims gathered to migrate to Pakistan. Most of the men were lured to a town pond on the pretext of forming a peace committee, where they were surrounded and killed. Young girls from their homes were abducted.

The Massacre at Reasi

Reasi, a town located about 45 miles from Jammu and surrounded by the Chenab River on three sides, became a site of mass violence during the events of November 1947.

With a Hindu-majority population on the left bank of the Chenab, Katra, a nearby town at the foot of the Vaishno Devi hill, had long been a hub for the Hindutva activities. The leaders of these activities included Kali Dass, Rikhi Dass, Shubh Dutt, Dina Nath (a retired ranger), and Shambu Nath, son of Gana Ram.

At Katra, the Sangh was bolstered by a militia group organized by local authorities, including Govardhan Singh (Wazir-i-Wazarat) and Jia Lal Darbari (ASP), among others. This militia was commanded by Captain Kishan Singh and Captain Omkar Singh of Bijepur, alongside retired Zaildar of Biddha. Inder Singh Namdar and his militia company from Katra played a crucial role in supporting this armed effort.

While much of Reasi’s left bank was decimated, the area on the right bank of the Chenab was spared. Inhabitants received timely warnings, and many fled towards Gool or Rajouri, with some escaping further to Pakistan or the neighboring Kashmir territories.

On November 4th, 1947, Dogra troops arrived in Reasi. A lorry loaded with soldiers from Jammu stopped near a nullah about 1.5 miles from Reasi town.

Muslim passers-by brought this alarming news into the town, already anxious given the reports of mass killings in nearby areas.

A “Peace Committee,” comprising Hindus and Muslims, had been formed days earlier to maintain communal harmony. However, despite the committee’s efforts, tensions escalated as the Dogra troops’ presence in the area stirred fears of violence.

Two Muslim elders—Khawaja Amkalla Rais and Khawaja Aziz Din (also known as Chaudhri Aziz Din)—well-respected leaders in Reasi, approached Sub Divisional Magistrate Thakar Govardhan Singh to inquire about the arrival of the troops. Singh, a Dogra, assured the elders that their town was secure due to the Peace Committee’s work. But as soon as the two elders entered Singh’s residence, they were brutally beheaded. Their deaths sent waves of panic throughout Reasi.

At 2:30 PM, (November 4), Dogra troops, who had taken positions, began firing indiscriminately on the Muslims of the town. Many sought refuge in the haveli of Mian Nizam-ud-Din. Sultan Muzaffar-ud-Din, a local sub-judge who attempted to visit the sheltered residents, was killed by Hindutva brigades.

This marked the start of a full-scale attack on Muslims in Reasi, which continued from the 5th to the 6th of November. The assault was led by Dogra troops, alongside RSS volunteers. Muslims, including women and children, were slaughtered, and young women were abducted.

Several Muslims were taken to the premises of a local court, where Maharaja Pratap Singh had been born and where a commemorative plaque had been installed. Most of these captives were killed on the court premises.

One particularly tragic incident involved the daughter-in-law of Maulvi Ghulam Haider Khan, the father-in-law of Mr. Abdul Aziz Salehria (later Director of Education, Azad Kashmir). She was found murdered in her home, cradling her dead infant on her chest.

Khawaja Ghulam Ali, a police officer originally from Bhadarwah, narrowly escaped the massacre. He managed to reach the police station, but his colleagues, who should have protected him, handed him over to the RSS volunteers.

They inflicted unspeakable cruelty on him, mutilating his limbs one by one and savoring his agony before finally killing him. Malik Abdur Rashid, a survivor and resident of Reasi who later became Director of Village Aid in Azad Kashmir, estimated that 3,000 to 4,000 Muslims were killed in the district during this wave of violence.

Thakar Govardhan Singh, the Sub Divisional Magistrate involved in the massacre, was later arrested under the orders of Sheikh Muhammad Abdullah and imprisoned in Jammu.

Rajouri and Surrounding Areas

Rajouri, located about 70 miles from Reasi, was also subjected to horrific violence. A Muslim-majority area, the government had deployed a company of troops to Rajouri prior to the massacre. However, following the massacre, additional troops from Reasi were sent to “clear” the Pauni Bharakh region and push through to Rajauri. The soldiers intended to pass through Dharamsal and Sialsui en route but were mistakenly diverted to Arnas in the Gool region.

This error likely saved countless lives in Rajauri, as the town ultimately fell into chaos.

Sheikh Abdullah is chosen head

In the aftermath of the 1947 partition, Sheikh Muhammad Abdullah was thrust into a political and humanitarian crisis as communal violence erupted in Jammu.

Struggling to maintain political balance while protecting Muslim lives, he immediately convened with Indian and state officials, expressing “anger and shock” at the violence in Jammu.

He cautioned that if the bloodshed persisted, he could not ensure the safety of non-Muslims in Kashmir. Yet, he was disheartened when Muslim officers refused to intervene, “worrying for their own life.”

Sheikh Abdullah also voiced his frustration to Pandit Nehru, stressing the “absolute necessity” of ending the violence.

In an August 3, 1949 letter, he detailed to Nehru the impact of communal forces infiltrating areas the Indian Army had taken in Rajouri and Poonch.

“The most dangerous aspect of the Parishad’s activities took the form of sending bands of looters and murderers in the wake of the Indian Army victories…where they killed, burnt, and pillaged the local Muslims. The Indian Army was thus brought into disrepute by these agents of the Parishad camouflaged in military uniforms.”

Determined to aid the Muslim population, Sheikh Abdullah visited refugee camps in Jammu and worked with local Muslim leaders to strategize for their safety. Speaking at public meetings, he confronted Dogra leaders directly, telling the “chivalrous Rajputs” of Jammu,

“But you murdered innocent barbers and washermen who knew nothing about politics. How unjust it was to kill children and women who did not even know the Muslim League and Pakistan.”

Despite his efforts, Abdullah’s role as Head of the Emergency Administration, starting on October 30, 1947, drew criticism from some who felt he had not done enough.

Records suggest, however, that Abdullah only formally took on the role after the violence had already reached a peak and that other officials, such as Mehr Chand Mahajan, had already taken measures. In one incident, Mahajan recalled how Abdullah “accused me of being a party to the shooting” of Muslim soldiers being evacuated from Jammu.

Mahajan also noted Abdullah’s deep emotional involvement, saying, “The slightest injury to a Muslim touched the very core of his heart.” Abdullah’s distress was evident as he attempted to send trusted officers like Chaudhry Niaz Ahmad to manage the crisis, though many were reluctant, citing fears for their own safety.

Local forces struggled to protect Muslim convoys against armed bands, with Abdullah’s emotions evident when visiting camps, where, eyewitnesses recalled:

“He wept for a long time.”

Sheikh Abdullah’s criticism extended to the Maharaja’s role in the violence. He voiced his mistrust, believing that Maharaja Hari Singh’s ties with Mahajan undermined any genuine effort to safeguard Muslims.

Abdullah wrote to Mahatma Gandhi, underscoring his frustration and calling for the Maharaja to be held accountable. Recognizing the threat to Muslim lives, he ultimately saw migration to Pakistan as a necessary step, given his limited confidence in the local authorities.

In a decisive move in 1948, Sheikh Abdullah stopped the salaries of Dogra forces, sparking protests from Hari Singh and his son, Karan Singh. He defended his action to Nehru, saying,

“Their hands are drenched in blood of innocent Muslims.”

This was coupled with his demand for the Maharaja’s abdication, warning India of an inquiry into what he termed the “genocide in Jammu.”

Abdullah’s advocacy was pivotal in the abdication of Hari Singh in May 1949, a decision supported by Sardar Patel and Vallabhbhai Ayyangar. “In the larger interests of India, Hari Singh was successfully persuaded by Patel and Ayyengar to abdicate in favor of his son.”

Abdullah’s commitment went beyond political demands.

His close associate Bakshi Ghulam Muhammad, on Sheikh’s directions spearheaded rescue missions, retrieving abducted Muslim girls from Hindu Rajput homes, reuniting them with families that had fled to Pakistan. These operations helped “the remnants of the Muslim population regain their morale” amid ongoing fear and despair.

Meanwhile, Gandhi’s response to the atrocities was stern. He openly criticized the Maharaja, asserting that he must be held accountable. Gandhi’s support for Abdullah’s advocacy lent international weight to the crisis, and he advised the Maharaja to step aside, urging Sheikh Abdullah and the Kashmiri people to “deal with the situation.”

Despite Abdullah’s efforts, some critics accused him of exaggerating the crisis for political leverage.

Mahajan dismissed his accusations as “false but malicious,” and he reportedly lied after Abdullah asked him to leave Jammu, as Abdullah believed he had done little to prevent Muslim suffering.

This intervention marked a turning point in the region’s leadership, with Gandhi’s support amplifying Abdullah’s efforts and helping to draw international attention to the plight of Jammu’s Muslims during the volatile 1947 period.

Author Profile

Latest entries

- Representational ImageREGIONALApril 13, 2025First action under new Waqf Amendment, Bulldozer demolishes 20-year-old madrasa in Madhya Pradesh