The name of Qadir Ganderbali, often referred to as “Ister” (iron press), had largely faded from Kashmir’s political discourse for some time. However, late Kashmiri Pandit activist Sampat Prakash revived the name by frequently invoking “Ister,” symbolizing the severe methods allegedly used by Ganderbali.

Infamously known for his harsh and brutal tactics, Ganderbali’s name alone was enough to instill fear among Kashmiris, especially the older generation. His brute measures continue to haunt his legacy. In this essay, we explore the life and career of Qadir Ganderbali to better understand his impact and significance.

Qadir Ganderbali, born into the Sheikh landlord family of Ganderbal, began his career as a sergeant in the Jammu Kashmir Police during Maharaja Hari Singh’s reign. Rising to Deputy Inspector General (DIG), he was among the first appointed to the Indian Police Service (IPS) in Kashmir in 1958. He was married to Raj Begum, a celebrated Kashmiri singer, and was the inaugural recipient of the Police Medal for Gallantry in J&K State.

When Sheikh Abdullah was arrested in 1953, Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad’s rule marked a transformation of the state into a police state. This period saw the establishment of a specialized police unit known as the Special Staff, led by Qadir Ganderbali, who was infamously nicknamed ‘Qadir Natta’ by Kashmiris. Ganderbali was granted extensive powers, which he used with brutal efficiency, defying legal boundaries. Though several theories exist around Qadir Natta being a different person, but historian Aijaz Ashraf Wani in What happened to Governance in Kashmir states that Ganderbali was called Natta by Kashmiris.

The period also witnessed severe political repression through a notorious group known as the “Khoftan Fakirs,” believed to be commanded by Ganderbali. Operating after the Isha prayer, these men patrolled the streets of Srinagar and other areas. They were infamous for their brutal actions, including the confiscation of radios and the severe beatings of house owners.

The Khoftan Fakirs, equipped with wooden dandas (Hatabs), knives, and axes, marched through Srinagar to maintain control of Baskhi and terrorize the locals. Their efforts were not confined to Srinagar; they extended their control to Kargil, Ladakh, Handwara, Shalateng, and Bandipora, contributing to a pervasive atmosphere of fear and repression. The group was instrumental in suppressing dissent and enforcing political control MM Isaaq writes in Nid e Haq: Memories of M M Isaaq.

Under the police supervision of Ghulam Qadir Ganderbali, who later retired as DIG, the Khoftan Fakirs enforced a brutal crackdown on dissenters. In 1962, some of these enforcers were controversially sent to the Ladakh front to combat the Chinese army, with many never returning.

Ganderbali’s reign of terror specifically targeted anti-India elements, supporters of Sheikh Abdullah, employing methods of torture and oppression (using iron press on the bodies of the arrested) that became synonymous with his name in Kashmir, as noted by Aijaz Ashraf Mir in What Happened to Governance in Kashmir?

In addition to the Khoftan Fakeers, the ‘Peace Brigade’ and Special Staff was organized under Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad’s administration. This group, effectively a band of thugs with government backing and overseen by Ghulam Qadir Ganderbali, was employed to suppress suppoters of Sheikh Abdullah and intimidate opponents of the Bakshi-led administration.

Mir Qasim, a contemporary and cabinet colleague of Bakshi, described their role as creating chaos at public events of opposing groups, only to ‘restore’ order in a manner akin to “graveyard peace.”

During this period, organized thuggery proliferated, with Peace Brigade members disparagingly referred to as “kuntra-pandah” due to their meager pay of Rs 29 and 15 annas.

The widespread network of espionage and fear of denunciation made every interaction suspect under Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad’s rule. This atmosphere of mistrust and oppression severely impeded the moral and cultural reconstruction of Kashmiri society, undermining efforts to establish a democratic framework, as noted by Bazaz.

Qadir Ganderbali dismantled a trans-border gang led by Munawar Daku, a notorious criminal with a Rs 50,000 reward from Pakistan on his head. Ganderbali captured him in the rugged mountains of Gulmarg, where Munawar Daku was armed with carbines, while the Indian and Pakistani armies had only .303 rifles. Pakistan offered a reward through its mission in Islamabad, but Ganderbali declined, stating he could not accept a reward from an enemy country causing trouble in Kashmir.

In the significant Kashmir conspiracy case against Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah, Mirza Mohammad Afzal Beg, and others, Qadir Ganderbali played a crucial role in gathering evidence for the indictment.

The case, which began on May 21, 1958, and lasted six years, involved prominent London criminal lawyer Dingle Foot, who cross-examined Ganderbali. Dingle Foot reportedly warned Sheikh Abdullah of the strong case Ganderbali had built against him.

When the holy relic of the Prophet was stolen from the Hazratbal shrine on December 27, 1963, it caused widespread public outcry. An SIT, led by B.N. Malik, included Qadir Ganderbali as a key member. Ganderbali established a special cell at the Shergarhi Police Station in Srinagar to investigate the theft. His efforts were instrumental in managing the law and order situation and led to the successful recovery and reinstallation of the holy relic at the Hazratbal shrine.

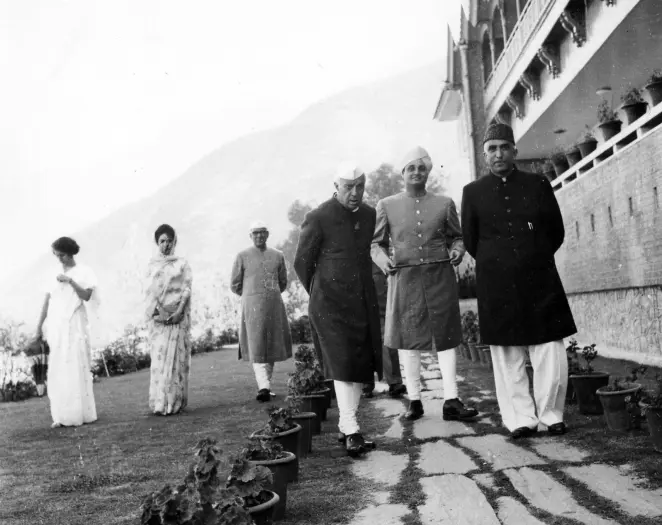

Qadir Ganderbali passed away from Tuberculosis on February 21, 1970, at AIIMS. His body was flown to Srinagar, and the Ministry of Home Affairs issued special orders to avoid embalming as a mark of respect for his dedicated service. Prime Minister Indira Gandhi and Home Minister Y.B. Chavan attended his departure at Palam airport in New Delhi.