Hammad Bukhari

“There was foul air in the city, and he was vomiting and had fever and a few loose motions. The hakim gave up, and he slowly became lifeless. These were the melanchonic words of my beloved grandmother when she narrated to me the story of how she became a widow, when she was still in her early twenties,” writes Gulzar Mufti, Non-executive Director East Sussex Health CCG, regarding the Cholera epidemic of Kashmir of the late 19th century in his research paper.

Cholera, locally known as Haiza, spreads through contaminated water supplies, unhygienic conditions, and high human mobility, making it a recurrent catastrophe for the masses in Kashmir.

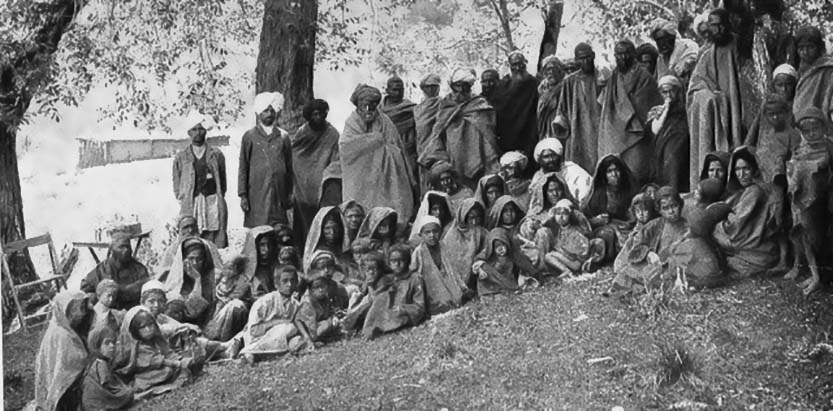

Cholera reached the Valley repeatedly, usually through Rawalpindi and Punjab, utilizing the Jammu Srinagar trade system and the Gilgit Transport circuit, which used to transport materials and troops into the Dogra kingdom. Epidemics had a grim seasonal cycle, flourishing in summer months, reaching their peak in autumn, and waning with winter. Although cholera was identified in Kashmir as early as 1598, the 19th century saw at least a dozen major outbreaks: in 1824, 1844, 1852, 1858, 1867, 1872, 1875-76, 1879, 1888, and the worst one in 1892, which took 11,712 lives in Srinagar alone, the deaths ravaged Anantnag, but the number remains largely unknown.

Nawab Mautamad Khan, one of the paymasters in Jehangir’s Army, says in Ikbal Namah that plague raged in a severe form in Kashmir. The first ever reported outbreak of plague in Kashmir occurred between November 1903 to August 1904, costing 5 thousands of lives. Large pneumonic Plague outbreaks have occurred in Kashmir during the year 1910-11, which accounted for about 1,400 deaths. Kashmir, with an elevation of about 5,000 feet and climatic condition being cold climate, could be a reason for the spread of pneumonic Plague.

Teague and Barber, as a result of their investigations in Manchuria, believe that the essential conditions for a rapid spread of pneumonic plague are a low temperature with considerable humidity, thus permitting droplets containing plague bacilli to remain

The disease followed established economic and military corridors. Dogra administration movements, Hindu pilgrimages, and trade caravans carried cholera deep into the Valley, with the outbreaks being centered in Banihal, Anantnag, and Baramulla. The Jhelum River, Srinagar’s lifeline, also became the primary vector of death. The worst-hit locations, like Habba Kadal, were highly populated, and the inhabitants relied on its contaminated water for drinking, washing, and sanitation.

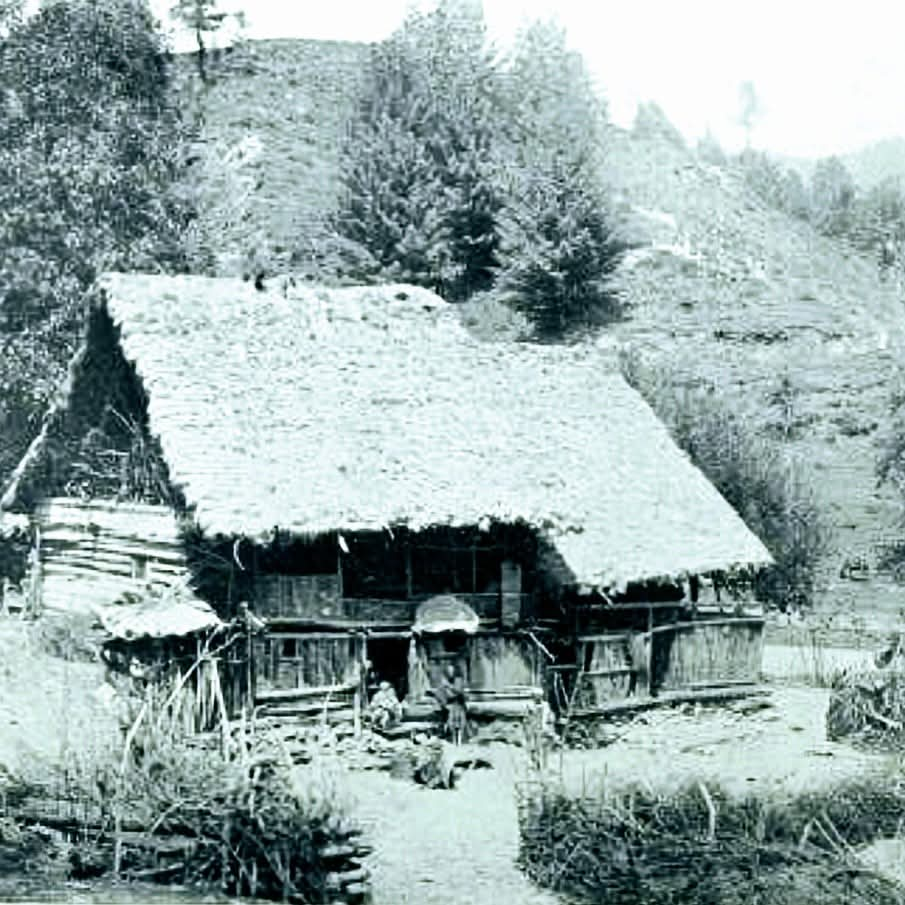

In 1888, the plague spread to Baltistan and Gilgit for the first time with Dogra troops and workers working on military infrastructure projects. As the ruling classes lived in fairly clean palaces, protected from the worst impact, the working class suffered in each epidemic. Public health did not figure among the priorities of the state. The Dogra regime was obsessed with military conquest and tax gathering, while the conditions of lot of the working classes, serfs, peasants, and laborers worsened.

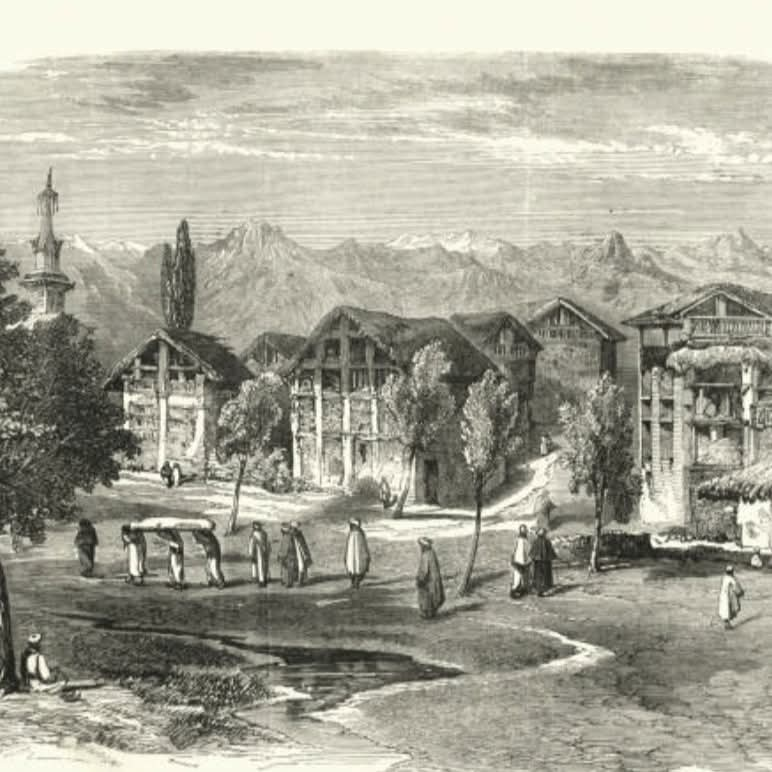

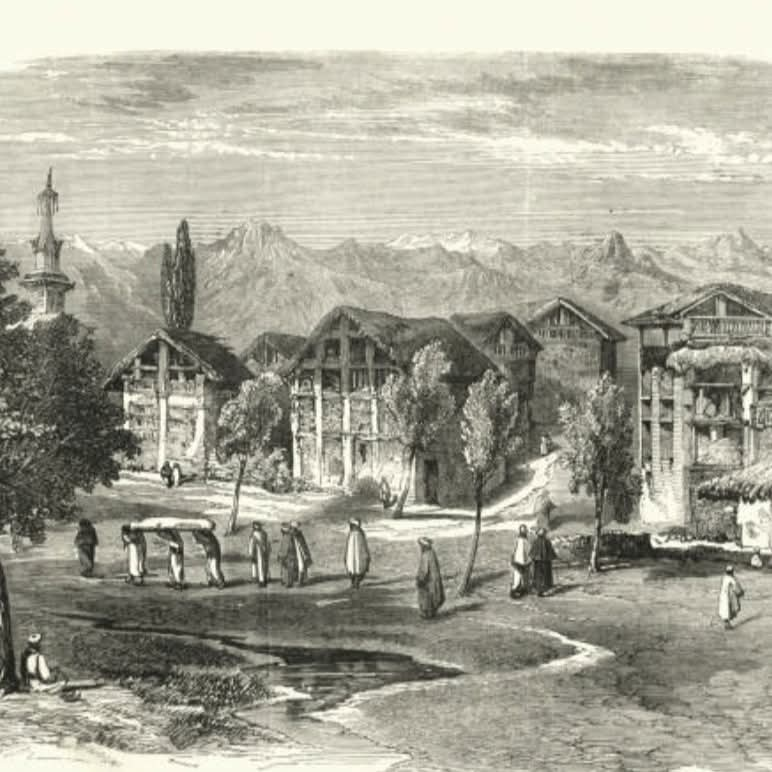

All travelogues and accounts from those times detail Kashmir’s stunning natural scenery, but almost all also cite the grime of its towns, particularly Srinagar. Smelly slaughterhouses, bloody cowsheds without ventilation, congested burial grounds, and open garbage dumps dominated the cityscape. Stray creatures, some living, some famished, and others dead, filled the streets. With no sewage system, alleys became mud puddles with human excrement mixed in, since latrines were a luxury.

Dr. A. Mitra, who was the Chief Medical Officer of Kashmir in 1892, called Srinagar one of the most unhygienic locations on the planet:

“The Kashmiris are notoriously dirty and careless about personal cleanliness. In an area of six square miles, there live a population of 118,960 in low and filthy houses constructed irregularly along narrow, winding alleys. Ventilation is nonexistent. Few houses possess latrines, and alleys serve as open defecation grounds. Two hundred sweepers are employed by the municipality, but that is microscopic considering the needs of such a huge population. There is no drainage. Slush, filth, and ordure are washed by storm-water into the river and Nalla Maar, which supply the city with drinking water.”

The aftermath was tragic. Infectious illnesses and outbreaks swept through the population at regular intervals. Even though Kashmir possessed rich natural resources in terms of plentiful freshwater supplies, lack of care, sanitation infrastructure deficiency, and bureaucratic lethargy caused these same resources to become harbingers of death.

In Anantnag, an entire mohalla near the present-day Janglatmandi Hospital was said to have been emptied in a week during the 1892 outbreak,” recalls Mohammed Jabar Khan, an old resident of Anantnag town. He recalled his grandfather saying, “So many people died that local gravediggers couldn’t keep up. A small orchard was temporarily turned into a graveyard. Elders say people stopped cooking food in the evenings, fearing the smell would attract ‘margan’, spirits of the dead.”

An old folk tale from Reshi Bazar of the town mentions a peer saab (saint) who warned the neighborhood of an impending outbreak. He asked each household to keep a burning coal pot at the entrance and hang neem leaves, but the advice was largely ignored. When the epidemic came, only three houses survived with no casualties. Those houses, it is said, maintained the ritual. Whether spiritual or coincidental, the tale became part of the area’s collective memory, passed down especially by womenfolk during winter gatherings.

Noticing the deteriorating health situation, the Srinagar Municipality Committee was formed in 1886, and Dr. A. Mitra was its first president. It was a state-run organization, though, and any suggestions of structural reform were met with opposition from the people. For instance, when Habba Kadal was burned to the ground, officials proposed to rebuild the quarter with organized sanitation, but the opposition made them drop the idea.

However, by the beginning of the 20th century, reforms gradually materialized. Public bathing ghats and latrines were built. Embankments and streets were paved, roads were broadened, and parks evolved, such as the building of Pratap Park in 1920. Drainage was implemented, and municipal staff started disinfecting. The use of kerosene lamps on roads was substituted with electric lamps in 1920. In 1941, a Health Officer and Municipal Engineer became part of the administration.

But these reforms arrived decades too late. The 19th-century Kashmiri proletariat had already suffered through several catastrophic epidemics before any concrete public health measures were taken. The question remains—why did the state ignore sanitation for so long?

The ruling elite had little incentive to invest in sanitation reforms. Military campaigns, revenue collection, and elite privilege remained the primary concerns of the Dogra administration. Unlike British-administered Punjab, where rudimentary public health policies had been introduced by the late 19th century, Kashmir lacked state-led disease control mechanisms.

The economic networks that enriched the ruling class also enabled the transmission of disease among the masses. The pilgrimage economy, trade routes, and forced recruitment into labor made Kashmir highly susceptible to cholera from neighboring regions.

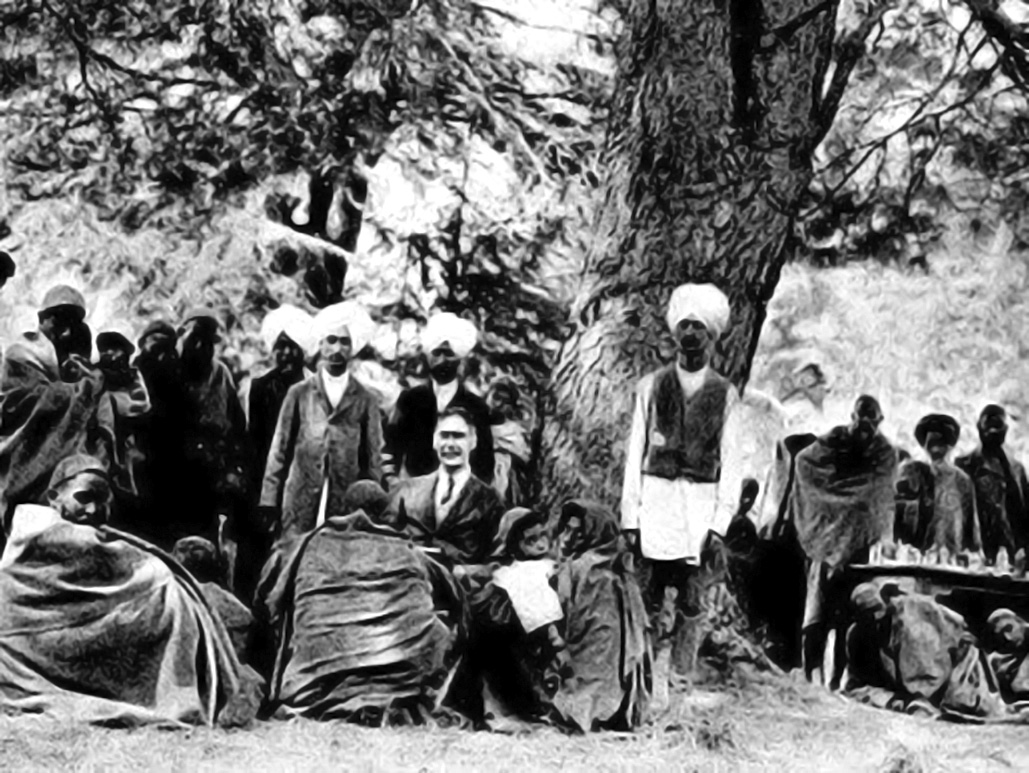

European medical missionaries, including Dr. William Elmslie and Arthur Neve, tried to stem the outbreaks, but state medicine was non-existent. The masses were not provided with any medical care, and traditional ritualistic measures only aggravated the crisis.

Recurring epidemics were met with reactive, piecemeal responses. In the 1892 epidemic, Dr. Mitra spearheaded efforts to stem the spread:

25 hakims (traditional doctors) were given training and medicines.

Additional doctors were recruited from Agra and Lahore.

Srinagar was divided into nine districts for better healthcare distribution.

The sale of rotten vegetables and unripe fruit was banned.

Bonfires of sulfur were burned in every locality to “purify” the air.

The public was informed via drumbeats to boil water before drinking.

Even with these efforts, the official death toll came to 11,712. Successive epidemics in 1914, 1921, and 1931 continued in the same pattern, i.e. delays in response, stopgap measures, and ongoing state neglect.

By the early 20th century, British pressure and growing civic awareness prompted actual sanitation reforms. In 1890, the British Resident, Col. Parry Nisbet, started a clean water project for Srinagar. The devastating 1892 epidemic once again highlighted the need for clean water.

A barrage was constructed over the Sindh River, diverting water to Nishat for supply. Problems still existed; leaky pipes and the absence of filtration resulted in ongoing pollution. In 1929, the supply of water was unsatisfactory. The Public Works Department asked Paterson Engineering Company to set up a chlorination plant. Steel pipes were used instead of wooden pipes by 1937, and a purer supply of water was provided.

As per oral tradition, In the autumn of 1892, as cholera swept through the Valley, a wedding procession was making its way from Baramulla to a village near Sopore. The bride, a young woman of barely sixteen, villagers say was the only child of her parents—beautiful, soft-spoken, and dearly loved.

As the baraat moved along the banks of the Jhelum, someone in the group began to vomit and collapse. They thought it was just fatigue. But within hours, several others showed symptoms—fever, loose motions, and labored breathing. Panic broke out. The wedding party halted near a village temple, but the locals, already terrified of the disease, refused to offer shelter. One by one, the guests began to die. The groom, too, collapsed on the riverbank, foaming at the mouth.

Only the bride remained—unharmed, but alone.

She refused to return to her parents, saying, “A bride leaves her home once. I won’t bring death to my doorstep.” She sat for three days beside the river, reciting Naat and prayers, feeding crows with the last of her wedding sweets. On the fourth morning, she was found lying still under a chinar tree. She had starved herself to death.

Locals buried her near the riverbank. For years, boatmen claimed to see a woman in red standing by the water in autumn, staring at passing boats. This story is still whispered by elders near Baramulla, especially when wedding seasons and cholera outbreaks coincide.

Concurrent with sanitation reforms, social changes remodeled Kashmir. The eradication of beggar (forced labor) in the early 20th century brought an end to one of the most exploitative feudal practices. Kashmir’s 19th-century cholera epidemics were not merely health crises, but a reflection of underlying socio-economic contradictions. The Dogra state’s army fixation, sanitation neglect, and unequal distribution of resources resulted in repeated outbreaks that mostly hit the masses.

Even today, public health outcomes are shaped by class dynamics, economic policies, and state priorities. The cholera outbreaks of the past serve as a reminder that epidemics are never just about disease; they are also about power, privilege, and neglect.