Syed Hammad Bukhari

On January 4, 1964, at 5:30 p.m. the holy relic of Hazratbal Shrine which is a strand from the bread of Prophet Muhammad was found again after being missing from 8 days which led to a social unrest in the state of Jammu Kashmir. This soon took a Political turn later causing G.M. Sadiq to be elected as Prime Minister replacing Shamsuddin.

Since arrest of Sheikh Abdullah in 1953, many provisions of the autonomy of J-K had been revoked with time, however, the March 28, 1965, amendment by Sadiq was seen as last nail to the coffin.

This changed the position of Jammu Kashmir from Self-determination to the level of autonomy it would receive with accession to the Union of India. However, under Sadiq’s rule, initiatives were taken for Sheikh Abdullah’s release.

On April 5, 1964, Sadiq issued a statement saying that the conspiracy case against Sheikh Abdullah would be withdrawn soon. That was done in the next two days and, on April 8, Sheikh Abdullah was released.

On April 29, Sheikh Abdullah met PM Nehru in Teen Murti House and expressed his desire to go to Pakistan to try to pave the way for a peaceful settlement of the issues between India and Pakistan and propose a confederation between two countries.

Sheikh Abdullah went to Pakistan on May 24, 1964, along with Mirza Afzal Beg, Maulana Masoodi, Khawaja Mubarak Shah and a few others. He talked of his confederation proposal to President Ayub Khan. Ayub Khan rejected the proposal and described it absurd as per his autobiography Friends not masters.

On May 29, Nehru died so Sheikh Abdullah had to cut short his Pakistan visit and he rushed to New Delhi. Since Nehru was no more, Sheikh couldn’t proceed further his proposal. About ten months after his Pakistan visit, Sheikh Abdullah wanted to go for Hajj via England, Egypt and Algeria.

The Government under Lal Bahadur Shastri allowed him. He left for Algeria in March 1965. In Algeria, he met the Chinese Prime Minister, Chou En-lai, who was there to attend an Afro-Asian Conference. This meeting raised outrage in India because of anger against Chinese aggression in 1962 which was yet there. This aggression made the Chinese as India’s enemy and any act of meeting them as Anti National.

The Government of India sent him a message to return immediately after performing Hajj or else his passport will be impounded. After returning to India, he was arrested at Palam Airport on May 7, 1965.

In 1965, war broke out between India and Pakistan again which saw an UN ordered Ceasefire under Tashkent Declaration on January 10, 1966 signed by Lal Bahadur Shastri and Ayyub Khan. Later Shastri died from a massive Heart attack in Tashkent which ended his 20 month’s premiership. Shastri was replaced by Indira Gandhi as Prime Minister of India.

During this era, RAW was formed and armed wing of Azad Kashmir Plebiscite front, JKNLF (later succeeded by JKLF) became primarily active hence executing the Ganga hijacking in 1971. NLF planned this airline hijacking inspired by Dawson’s field hijackings done by PFLP, A Palestinian Left wing Militant group, under Patrick Argüello and Leila Khalid. Hashim Qureshi and Ashraf Qureshi did the Hijacking planned by Maqbool Bhat in order to draw world’s attention to Kashmir issue. The hijacked plane was landed in Pakistan giving Government of India and excuse to block the airspace between East Pakistan and West Pakistan. Later the hijackers were arrested as Indian agents and it was revealed that Qureshi worked as a double agent for RAW. This ignited the Bangladesh liberation war of 1971 hence breaking the Bengali speaking East Pakistan off as a new country namely Bangladesh consisting of majority population of then Pakistan.

G.M. Sadiq’s health deteriorated so he was taken to Chandigarh for treatment where he died on December 11, 1971. Mir Qasim was given the position of CM by Governor Bhagwan Sahay on 12 December. He announced to hold fresh elections in 6 months. This announcement divided the Plebiscite Front into two factions – those who wanted to participate in the elections and those who favoured a boycott.

Maulana Masudi announced the participation of Plebiscite front in elections in Hazratbal. He was arrested. Qarra was also arrested as he also insisted to persuade Plebiscite Front chief to participate in elections. Begum Abdullah was banned from entering into Srinagar.

The elections resulted in the victory of Congress with 57 seats out of 74. Jamat won 5 seats, the Jana Sangh won 3 and Independents won 9. A few Independents later joined Congress.

The road to the accord

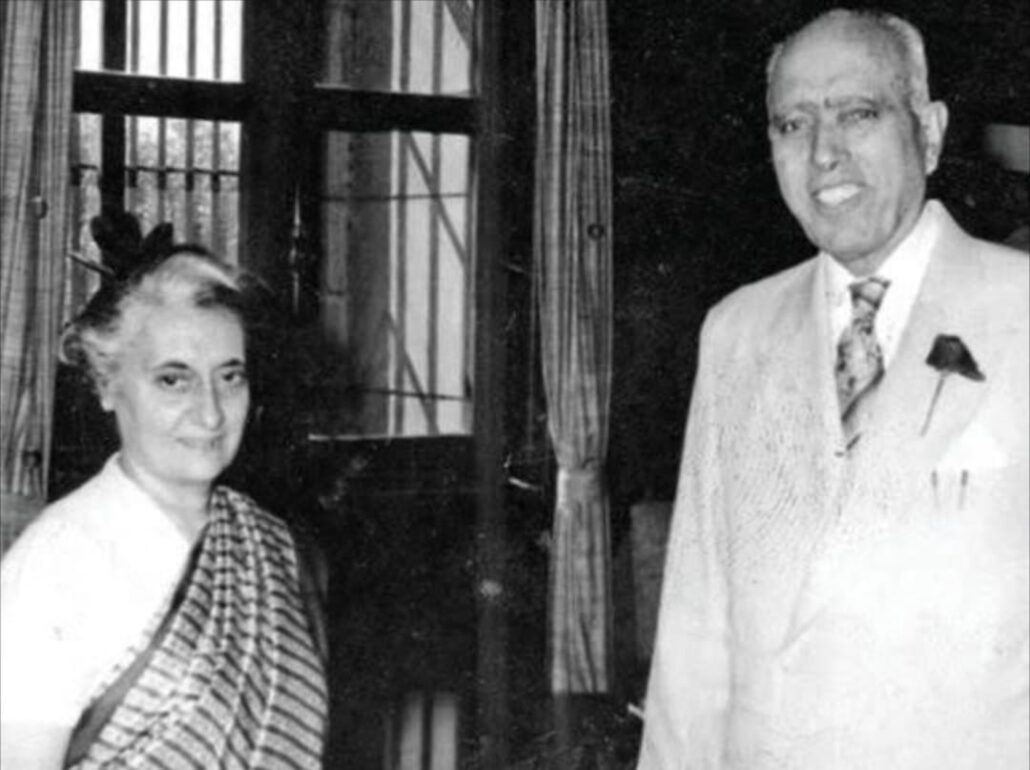

The events leading to the Indira-Sheikh Accord of 1975 stand as a pivotal chapter in the history of Jammu Kashmir, reflecting the complex interplay of trust, power, and reconciliation.

Mir Qasim, the then Chief Minister, emerges as a key architect who sought to bridge the chasm between Sheikh Abdullah and the Indian leadership, particularly Prime Minister Indira Gandhi.

This account, drawn from Qasim’s autobiography, Dastaan e Hayat, provides rare insight into the tense yet transformative dialogue between two towering figures of Kashmiri politics. It captures the candid exchanges, mistrust, and negotiations that culminated in the Sheikh’s return to power and the eventual reshaping of Centre-State relations.

As Mir Qasim reflects in his book, “It had been my objective, even as the Chief Minister, to restore to Sheikh Abdullah his rightful place in Kashmir.” After the 1972 elections, Qasim sought an opportunity to engage with Sheikh Abdullah directly, unencumbered by political intermediaries. That opportunity came during Eid that year. Taking the initiative without consulting Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, Qasim met with Abdullah, where the initial exchange was anything but cordial.

The Sheikh greeted him with a derisive laugh, saying, “You talk of reconciliation now.” Qasim admitted to his earlier actions, which included arresting Maulana Masudi and Mr. Qarra, banning Begum Abdullah’s entry into Srinagar, and effectively sidelining the Sheikh’s party from the electoral process. “This was the moment to explain my decisions,” Qasim remarked, emphasizing that his intentions were always toward fostering peace.

Once appeased, Abdullah asked, “Now say what you expect us to do.” Qasim made his offer clear: “You take over the chief ministership, and my party will accept you as its leader.” Abdullah, however, expressed skepticism.

The conversation turned to the potential implications of Abdullah’s return to power. “What will you do after taking over the government?” Qasim inquired. Abdullah responded decisively, “I will amend all the amendments in the State Constitution made after 1953 to extend the Central laws to the State.”

Qasim cautioned against confrontation. “If you used the Hazratbal platform to preach that the Central laws extended to the State after 1953 were bad, and that the Chief Minister should be called Prime Minister and Governor Sadr-i-Riyasat, then you would get a reply from the Delhi platform—and there would be no solution,” he warned.

Qasim instead proposed building trust with the Centre. “In a friendly climate, you can convince Mrs. Gandhi that these Central laws were not good for the State. What can be achieved with cooperation cannot be achieved with confrontation. Let me be the bridge between you and the Centre.”

Abdullah, however, questioned Qasim’s motives. “Are you tired of running the government because, as I am told, you have no money to run it? I hear you have mortgaged the new secretariat,” he alleged. Qasim dismissed these rumors as misinformation spread by vested interests. “I can assure you I can very well run the administration for ten years—I have the capability, and there is no financial crunch. I am offering to step down in your favor because it has been my long-cherished desire to bring about peace between you and the Centre. God willing, I’ll succeed in this mission. Please support me in this,” he implored.

Yet, Abdullah remained unconvinced of the Congress party’s reliability. “I have had a bitter experience; you can any time stab me in the back,” he said. To this, Qasim reassured him that the State Constitution empowered the Chief Minister to dissolve the Assembly and order fresh elections if necessary. “But this situation will never arise. I will not let it happen. I have my loyal colleagues who can never do or even think of that,” he vowed.

The accord itself was a product of months of meticulous effort and negotiation. It reinstated Sheikh Abdullah as the Chief Minister of Jammu and Kashmir, with assurances from both sides to work collaboratively within the constitutional framework. For Sheikh Abdullah, it marked a pragmatic return to power, and for Mrs. Gandhi, it was a strategic move to integrate Jammu and Kashmir further into the Indian Union.

Qasim’s role in the entire process was critical, as he facilitated the dialogue and bridged the mistrust. Reflecting on his efforts, he wrote, “The creation of mutual trust was a higher priority than anything else.” His tireless work culminated in the signing of the accord, which, while not resolving all issues, laid the groundwork for a more stable political climate in the region.

Sheikh writes to Gandhi in letter dated December 29, 1974:

“I hope you will agree with me that the only way to repair the vast damage done to the Indo-Kashmir relationship by the Arbitrary action of 9th August, 1953 is possible only through complete understanding and mutual trust. If this trust is lacking even in a very small measure, all our efforts to reach an understanding will prove fruitless. I have no doubt in my mind that the manner in which the Government of India systematically eroded both the letter and spirit of the special provision of the Union Constitution jeopardised the very foundation of the relationship so laboriously built over years of tireless effort and dedication. I recall with pain and anguish that once a former Home Minister of India publically characterised Article 370 as a “Tunnel” obviously implying that through it the internal autonomy of Kashmir will be eroded and this exactly was assiduously accomplished behind our back after 9th August, 1953.”

“I am aware of your views on the Centre–State relationship in respect of the State of Jammu and Kashmir. I have already explained to you that the clock cannot be put back and we have to take note of the realities of the situation. I am appreciative of the spirit in which you have expressed your agreement with the terms of the agreed conclusions.” Indira responded on February 11, 1975.

Sheikh was reluctant to reach any settlement without the restoration of pre 1953 position. Mir Qasim convinced Sheikh Abdullah to reach any settlement in order to make the peace talks successful.

The dialogue between Sheikh Abdullah and Indira Gandhi was fraught with mistrust, particularly over the Sheikh’s insistence on restoring the pre-1953 position, which would undo several constitutional changes made to integrate Jammu Kashmir with India.

According to Mir Qasim, Sheikh Abdullah insisted on the restoration of the pre-1953 position as a precondition, a demand Mrs. Gandhi rejected, stating, “The clock cannot be put back.” This disagreement resulted in a deadlock, creating an air of uncertainty in the state.

In a critical development, Sheikh Abdullah produced Mrs. Gandhi’s letter to Qasim rejecting any further talks. He declared, “The talks have not been deadlocked; they have ended.” However, persistent mediation efforts continued.

Efforts to break the stalemate culminated in Delhi, where Sheikh Abdullah’s trusted ally, Mirza Beg, engaged in intense negotiations. Initially reluctant to signing the agreement, Sheikh signed the agreement, after Mrs. Gandhi agreed that, “Pre-53 status was not out of the picture”, as Mir Qasim writes.

He suggest that only after the assurance of Mrs. Gandhi that the government would withdraw all laws imposed to weaken the regional autonomy, Shekh agreed to assume administrative responsibility.

On November 13, 1974, the historic Kashmir Accord was signed by G. Parthasarathi and Mirza Beg in New Delhi, signaling a new chapter in the region’s political history. This agreement reflected a delicate balance between Sheikh Abdullah’s aspirations and the central government’s vision, achieved through compromise and persistence.

Dr. Mustafa Kamal writes about Indira Abdullah accord of 1975 was intended to put a stop to the policy of gradually weakening the conditions of accession and 92 laws were implemented here after 1953, breaking of the earlier conditions had to be re-examined and those laws were against the sovereignty of the state. Jammu Kashmir required to be returned 53. “After the Shimla agreement, many more agreements were concluded which are still secret,” writes Dr. Afaq Aziz in Tareekh e Siyasat e Kashmir.

G. Parthasarathi, Vice Chancellor of Jawaharlal Nehru University was representing Indira Gandhi while Sheikh Abdullah appointed Mirza Muhammad Afzal Beg to represent him. Due to efforts of Mir Qasim and Congress, the tensions between Centre and State didn’t involved Kashmir’s accession to India but the level of Autonomy given to Jammu Kashmir.

Sheikh Abdullah was suggested by Mir Qasim that he should announce that he was willing to take over the responsibility of running the State administration. Sheikh Abdullah refused as he thought it would amount in signing a blank cheque for the sake of the post of Chief Minister. Later after persistence, an agreement was reached after Indira Gandhi agreed that she would not insist that Pre 1953 condition was out of question. The result of this hectic efforts was the accord signed by Parthasarathi and Beg in New Delhi one November 13, 1974.

Dr. Afaq Aziz in Tareekh e Siyasat Kashmir featured a column, “In fact, Sheikh felt that these leaders ruling Kashmir or wanting to rule Kashmir, would create even more suffering and misery for them by making the helpless and poor people a scapegoat for their own vested interests.”

Every leader is caught in his own trap, which is made by loyal and cunning friends and acquaintances around him, who from time to time tie a blindfold made of lies in the eyes of their leader.

“Sheikh was also caught in this trap. He must have felt that the good is that with power he can do good not only to the people but also to himself and also to the cunning loyal and other friends and acquaintances,” writes Dr. Afaq Aziz.

Mirza Afzal Beg called a press conference in New Delhi on February 6, 1975, to announce the Kashmir accord saying that it provided a lasting foundation for Centre State relations.

The following is the text of the agreement reached between G. Parthasarathi and Afzal Beg:

The State of Jammu and Kashmir which is a constituent unit of the Union of India, shall, in its relation with the Union, continue to be governed by temporary provisions of Article 370A[14] of the Constitution of India.

The residuary powers of legislation shall remain with the State; however, Parliament will continue to have power to make laws relating to the prevention of activities directed towards disclaiming, questioning or disrupting the sovereignty and territorial integrity of India or bringing about cession of a part of the territory of India or secession of a part of the territory of India from the Union or causing insult to the Indian National Flag, the Indian National Anthem and the Constitution.

here any provision of the Constitution of India had been applied to the State of Jammu and Kashmir with adaptation and modification, such adaptations and modifications can be altered or repealed by an order of the President under Article 370, each individual proposal in this behalf being considered on its merits ; but provisions of the Constitution of India already applied to the State of Jammu and Kashmir without adaptation or modification are unalterable.

With a view to assuring freedom to the State of Jammu and Kashmir to have its own legislation on matters like welfare measures, cultural matters, social security, personal law and procedural laws, in a manner suited to the special conditions in the State, it is agreed that the State Government can review the laws made by Parliament or extended to the State after 1953 on any matter relatable to the Concurrent List and may decide which of them, in its opinion, needs amendment or repeal. Thereafter, appropriate steps may be taken under Article 254 of the Constitution of India. The grant of President’s assent to such legislation would be sympathetically considered. The same approach would be adopted in regard to laws to be made by Parliament in future under the Proviso to clause 2 of the Article. The State Government shall be consulted regarding the application of any such law to the State and the views of the State Government shall receive the fullest consideration.

As an arrangement reciprocal to what has been provided under Article 368, a suitable modification of that Article as applied to State should be made by Presidential order to the effect that no law made by the Legislature of the State of Jammu and Kashmir, seeking to make any change in or in the effect of any provision of Constitution of the State of Jammu and Kashmir relating to any of the under mentioned matters, shall take effect unless the Bill, having been reserved for the consideration of the President, receives his assent ; the matters are a) the appointment, powers, functions, duties, privileges and immunities of the Governor, and b) the following matters relating to Elections namely, the superintendence, direction and control of Elections by the Election Commission of India, eligibility for inclusion in the electoral rolls without discrimination, adult suffrage and composition of the Legislative Council, being matters specified in sections 138,139, 140 and 150 of the Constitution of the State of Jammu and Kashmir.

After the accord

Historians have often argued that Sheikh Abdullah compromised on his staunch demand for the restoration of Jammu Kashmir’s autonomy in exchange for political power.

However, a closer examination of his political journey suggests a far more nuanced narrative—one driven by an unwavering commitment to preserving Kashmir’s autonomy and regional identity.

The accord, cannot be studied in isolation. Massive political developments on geopolitical and internal levels were taking place following Pakistan’s defeat in the 1971 war and the 1972 Simla Agreement, which declared Kashmir a bilateral issue between India and Pakistan.

After the war, Pakistan’s weakened position led it to introduce restrictive laws in Azad Jammu Kashmir (AJK) in 1974, tightening Islamabad’s control by diminishing regional autonomy and centralizing governance.

These measures limited the powers of AJK’s leadership and excluded areas like Gilgit-Baltistan from local representation.

Faced with Pakistan’s diminishing influence, the Simla Agreement’s bilateral framework, and Kashmir’s political leadership preoccupied with elections since 1971, Sheikh Abdullah saw limited prospects for achieving more than regional autonomy.

Under the accord, several “anti-government” cases, numbering in hundreds were withdrawn. Most of these cases had been registered from 1953-75. “Under the Indira-Sheikh Accord, cases against militants like Qureshi were withdrawn, even though many of them rejected the accord itself,” Josy Joseph writes in, How to Subvert a Democracy: Inside India’s Deep State.

On January 26, 1975, Daily Aftab reported, “Sheikh ke Beshtar mutalbat tasleem, 1953 ki position bhi bahaal’ (Most of Sheikh’s demands fulfilled, Pre 1953 position restored).

On January 19, Srinagar Times, a prominent local Urdu daily edited by Sofi Ghulam Mohammad, a leader of Janata Party seeking power in Jammu Kashmir, published a cartoon that sharply critiqued the Accord.

The cartoon depicted Mirza Afzal Beg, Sheikh Abdullah’s close associate and the chief architect of the accord, lighting a cigarette labeled ‘plebiscite’ with a lighter marked ‘greed for power.’

Historian Altaf Hussain Parra writes, “The Awami Action Committee and the Jamaat-e-Islamia in the Valley and the Jan Sangh in Jammu left no stone unturned to divert the public disappointment in their favor to carve out a political space in the state.”

Weeks later, on the day Sheikh would be restored to power after 22 years, an announcement was made on All India Radio that Sheikh had comprised on 1953 position and plebscite for power, Srinagar burst with protests.

This statement caused an outrage in Kashmir. “The Sheikh has sold out our interests for the sake of Chief Minister’s seat” was the chorus of the protest.

Eyewitness to the following developments, Mir Qasim writes, the Sheikh, who had been preparing to take office, was taken aback. On the day of the swearing-in ceremony, all arrangements had been made, yet the Sheikh was nowhere to be found for several hours. Journalist Shamim Ahmed Shamim walked in and asked what the delay was. “Sheikh Saheb says he will not come to take the oath,” he reported.

“I was stunned. I quickly rushed to the Guest House where the Sheikh was seated, furious. “You have made a statement as if I have sold out Kashmir for the chair of Chief Minister,” he thundered, his rage palpable.”

Mir Qasim states that he knew this was a moment of great tension. “I reassured him, urging, “Don’t be swayed by the Radio version. Come with me, take the oath, and I will publicly address the discrepancies in that statement.” After a few moments of consideration, the Sheikh, reassured by my sincerity, finally agreed. Together, we went to the Raj Bhavan (Governor’s House).”

The smear campaign, however, at a close monitoring of history appears to have been run on multiple fronts as Dr. Afaq Aziz suggests in his book. Even Sheikh hinted out at the campaign, which was being run by Congress. “On September 26, 1976, at Eidgah,” Sheikh explained “the accord in detail”. He said that the Congress had published the accord, which did not include the demands he had given to the Prime Minister. “It was written on the accord that I signed that I will take over the responsibilities of the government and I will start from the same place from which I left off in August 1953.” Sheikh Abdullah also said that “false pamphlets of the accord had been published by the Congress and distributed among people.”

The following years, after Sheikh took power, were fraught with tension between Indira and Sheikh, as Sheikh during constant communications sought the conditions of the accord to be fulfilled, including the restoration of 1953 position and the regional autonomy, Sheikh’s core fundamental ideal since the begining of his political career.

Several documents, including Altaf Parra’s first hand sources and thorough documentation in Fiscal Federalism and Diversity Accommodation in Multilevel States: A Comparative Outlook, it is documented that Sheikh reiterated his demand for greater autonomy. Months after the accord, “In April 1975, he was advocating for the merger of Jammu Kashmir with Azad Kashmir, a region administered by Pakistan. This shift was driven by Sheikh Abdullah’s long-held desire for a united, autonomous Kashmir.”

Eventually, the tensions escalated over multitude of issues including Sheikh’s persistent demand over return to 53 and the Congress pulled out of the government, however, some historical accounts state that Sheikh Abdullah pulled out of the congress support.”A year and half after the accord, Sheikh dissolved the assembly one fine evening after getting inputs that the Congress had decided to pull the rug the next day.” (Change of regime: 19 January 2009)

Abdul Khaliq Ansari, a former JKLF ideologue, recounts in his book Mata-e-Guroor, key discussions surrounding the Accord and the involvement of Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah and Mirza Mohammad Afzal Beg.

In 1976, due to political constraints, Ansari was unable to accept Sheikh Abdullah’s invitation to Srinagar.

Instead, Sheikh sent Afzal Beg to Britain as part of the Indian parliamentary delegation during the Commonwealth Parliamentary Conference to discuss the Accord.

Afzal Beg, despite being unwell, met Ansari and his associates, including Mohammad Bashir Tabassum, a stalwart of the Plebiscite Front, and Babu Abdul Rahim of Glasgow, both of whom were deeply committed to Kashmir’s autonomy.

Their discussions took place at Mirza Mohammad Sadiq’s residence in London and later at a reception organized in Birmingham’s Grand Hotel.

Babu Abdul Rahim facilitated the initial meeting between Ansari and Afzal Beg, who conveyed Sheikh Abdullah’s message and invited Ansari to Srinagar.

The reception in Birmingham became contentious when Lala Abdul Rahman, a fiery orator and advocate for autonomy, directly asked Afzal Beigh, “Is Kashmir’s accession to India truly irreversible?”

Afzal Beg responded, “Have you people read the Delhi Accord? It is incomplete. Every agreement involves some verbal exchanges,” he said.

He added, “I started the right to self-determination movement when the sun of my life was at its zenith. Now, as the sun of my life is setting, I cannot betray my country and nation. If we had needed the government, why would we have spent eleven years in prison? And if we had wanted to join the government, we would have done so immediately after the Shimla Agreement.”

Ansari also highlights the contributions of others in the autonomy movement, including Mohammad Bashir Tabassum and his brother, Professor Mohammad Nazir Tabassum, an intellectual who wrote high-caliber articles.

Arshad Ansari, a tireless political worker, tragically passed away young, leaving his brother Abdul Qayoom Tabassum Ansari to continue his work, including involvement in student movements.

The internal dynamics of the Plebiscite Front were also marked by disagreements between figures like Bashir Tabassum and Babu Abdul Rahim. Both were part of a six-member delegation that visited Srinagar under British passports for a Plebiscite Front convention.

Alongside Dr. Farooq Abdullah, Mirza Mohammad Sadiq, and Mohammad Arif Ansari, the delegation returned to Britain disillusioned after learning of the Accord’s terms. Despite the tensions, Afzal Beg remained resolute, asserting that the Accord was not a betrayal but a necessary step toward safeguarding Kashmir’s autonomy.

Mir Qasim writes that while he was engaged in an effort to “bring the Sheikh in the Congress fold, our partymen began a policy of confrontation with him.”

Sheikh very clearly refused to join the Congress and instead merged the Plebiscite Front into the National Conference at a public meeting of the Front in Mujahid Manzil in Srinagar, to counter Congress’s mounting pressure.

On October 19, 1975, he organised a public meeting of the National Conference, in Lal Chowk and formally became a member of NC, the party overtaken by his former loyalists.

Soon after this, he became its President. On April 24, 1976, he held the first massive convention of the Party.

“Mrs. Gandhi wrote to me saying that I had misled her about the Kashmir accord. “You had a plan of nearly finishing the Congress in the State,” she accused me,” writes Qasim.

Perhaps she quietly nurtured a hope that I would at some stage be able to deceive the Sheikh and “make him forget everything for the sake of the post of Chief Minister.”

Perhaps Mrs. Gandhi expected the Sheikh to “slide back from the very fundamentals of the Kashmir movement.”

“On the contrary, I did not find anything wrong in Sheikh Abdullah’s continuing commitment to these fundamentals, nor did I think a separate political party, if formed by him, would be a rival to the Congress.”

In his book Tareekh-e-Kashmir ke Gumshuda Awrak, Mirza Shameem Beigh recounts pivotal moments focusing on developments surrounding the Plebiscite Front in 1975.

On July 5, 1975, Mirza Muhammad Afzal Baig, head of the Plebiscite Front, submitted a written statement during a delegation session, declaring, “The working committee did not agree to the disbandment of the Plebiscite Front, nor did it deviate from its basic stand. Therefore, I, as the President of the Plebiscite Front, recommend to you the disbanding of the Plebiscite Front on the instructions and desires of Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah.”

Shameem explains that tensions between Sheikh Abdullah and Congress were escalating. Sheikh Abdullah reportedly stated that with the National Conference in existence, Congress’s support was no longer necessary.

When the Vice-President of the Plebiscite Front opposed Sheikh Abdullah’s proposal, Sufi Akbar decided to break away, forming a new party, Mahaz-e-Azadi. According to Beigh, “Sheikh Abdullah encouraged his close associates to fully support Sufi Akbar’s Mahaz-e-Azadi and directed other members to assist in building the new organization.”

Syed Hamad Bukhari is from Chewdara, Budgam. He studies Political science & economics. An enthusiastic Marxist, Hammad has been active in student activism and freelances as a video editor.