The martyrdom of Hamza ibn Abd al-Muttalib at the Battle of Uhud, 15 Shawwal, 3 A, marked, not only a military loss for the nascent Muslim community but also a profound emotional rupture in the life of Prophet Muhammad. ﷺ

Hamza was not simply an uncle; he was the Prophet’s close companion, protector, and an early convert who stood firm when Islam was most vulnerable. His death, and the manner in which it was inflicted, left a wound that never truly healed. The Prophet’s grief was not fleeting, it was sustained, recurring, and expressed subtly over the remaining years of his life. Despite the Prophet’s well-documented emphasis on patience in times of loss, the case of Hamza offers a complex picture of mourning: one where love, loss, restraint, and memory coexisted.

During the Battle of Uhud in the third year after Hijra, Hamza was killed by Wahshi ibn Harb, an Abyssinian slave who had been promised freedom by Hind bint Utbah, the wife of Abu Sufyan, in return for avenging her father’s death. Wahshi was instructed to kill only one man—Hamza. He stalked the battlefield until he found him, then killed him with a spear.

In a further act of cruelty, Hind mutilated Hamza’s body, cutting it open and, according to several reports, attempting to chew his liver. When the Prophet ﷺ came upon Hamza’s mutilated body after the battle, he was visibly shaken. He is reported to have stood in stunned silence before bursting into tears. According to Ibn Hisham, he said that he had never been more pained by any loss than that of Hamza (Sirat Rasul Allah, vol. 2, p. 71).

Ibn Saʿd, in his Tabaqat al-Kubra, records that the Prophet ﷺ called Hamza “Sayyid al-Shuhada” (leader of the martyrs) and wept openly over his body (vol. 3, p. 8). The mutilation of Hamza’s corpse was a particularly grievous affront not only to the Prophet’s heart but to the ethical codes of warfare and dignity in death.

The emotional depth of the Prophet’s mourning extended beyond the battlefield. Upon returning to Medina, he heard women from the Ansar mourning their relatives who had died at Uhud. He remarked quietly, “But Hamza has no one to weep for him” (Ibn Hisham, Sirat Rasul Allah, vol. 2, p. 73; Ibn Saʿd, Tabaqat al-Kubra, vol. 3, p. 8).

This seemingly incidental comment was not lost on the women of Medina. Moved by the Prophet’s sorrow, many of them began mourning for Hamza before lamenting their own kin. According to some reports, this became a lasting practice—Hamza was mourned regularly, even ritually, in the years that followed. These women understood that Hamza’s death was not only a personal loss for the Prophet but a symbolic wound for the entire community. Some sources even suggest that the Prophet ﷺ encouraged such mourning for Hamza before later discouraging wailing in general, in accordance with broader Islamic principles of composure and restraint in grief (Ibn Saʿd, vol. 3, p. 8).

The pain of this loss never truly receded. Years later, after the Conquest of Mecca, Wahshi—the very man who had killed Hamza—accepted Islam and came before the Prophet. ﷺ The Prophet did not deny Wahshi entry into the faith. Islam, in his view, offered redemption to even the gravest of sinners. However, despite forgiving Wahshi in principle, the Prophet ﷺ reportedly said to him, “Can you keep your face away from me?” (Ibn Hisham, vol. 4, pp. 29–30; Ibn Saʿd, vol. 3, p. 10). This statement cannot be read merely as discomfort. It was a recognition that some wounds are too deep for the heart to bear in plain sight. The Prophet’s forgiveness was sincere, but it was not an erasure of grief. The emotional memory of Hamza’s murder could not be undone by the formal act of reconciliation.

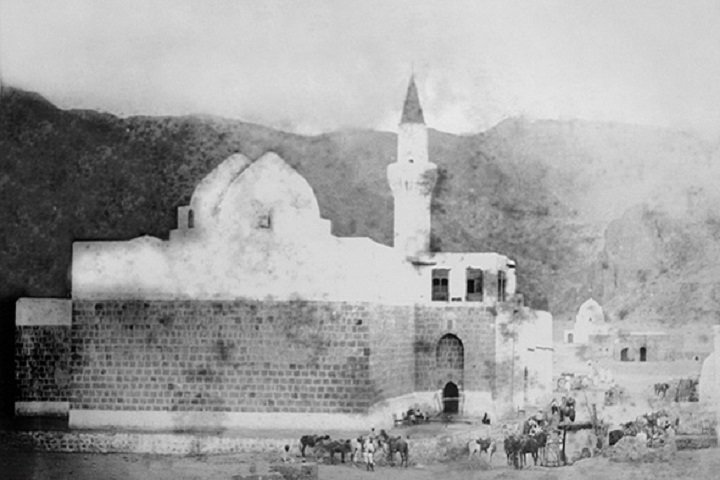

In the years that followed, the Prophet ﷺ continued to visit the grave of Hamza, particularly at Uhud. During his Farewell Pilgrimage, he made a point to stop at the site of the martyrs and offer prayers, choosing to stand at Hamza’s grave. He would reportedly say, “Peace be upon you for what you patiently endured. How excellent is the final abode” (Ibn Majah, Hadith 1571; Ibn Saʿd, vol. 2, p. 49). These visits were not obligatory rituals; they were acts of continued remembrance and silent grief. They signified that Hamza’s place in the Prophet’s heart—and in the narrative of early Islam—remained secure and central.

The Prophet’s remembrance of Hamza was not limited to the battlefield or graveyard. He spoke of Hamza as the finest of his kin. In one report, he declared, “The best of my family after me is Hamza” (al-Hakim, al-Mustadrak, vol. 3, p. 200). He was known as “Asad Allah wa Asad Rasulihi”—the Lion of God and His Messenger—an honorific that underscores both his valour and the depth of his sacrifice. Hamza was a foundational figure in the defence of Islam. He embodied a certain moral and physical courage that the Prophet ﷺ knew was rare, and perhaps irreplaceable.

To examine the Prophet’s mourning for Hamza is to see grief not as a sign of weakness but as a manifestation of human loyalty, memory, and spiritual depth. His sorrow was not a momentary cry at a funeral, but a lingering ache that lived within the silences of his everyday life. Even in forgiveness, even in ritual, and even in prophetic detachment from worldly emotion, his grief surfaced—in remarks, in facial expressions, in solitude. The Prophet ﷺ did not institutionalise this grief as a public spectacle, nor did he allow it to interfere with the responsibilities of leadership. Yet he also did not suppress it to the point of erasure.

This is what makes the case of Hamza so significant. It shows that within the framework of Islam’s call for composure and dignity in loss, there is space for profound emotional reality. The Prophet’s mourning was a reflection of this balance. He forgave Hamza’s killer, as was consistent with his spiritual vision. But he could not, and perhaps was not meant to, forget. Hamza’s death remained a presence in his emotional and prophetic life, a testament to a love that survived even after death.

The Prophet’s sustained grief for Hamza stands as an argument against any simplistic reading of Islamic ethics as emotionally sterile or stoically indifferent. It reveals the ethical possibility of grief that is neither performative nor denied, but remembered—quietly, persistently, and with honour.

The Prophet ﷺ did not grieve publicly for all his companions in the same way. That he did so for Hamza, repeatedly and enduringly, is itself a profound signal. It affirms that Islam’s commitment to patience in suffering is not a denial of feeling, but a reorientation of it—an invitation to feel deeply while holding on to divine trust. In Hamza, and in the Prophet’s mourning of him, we see not only the loss of a man but the moral vocabulary of remembrance itself.