Javid Ahmed

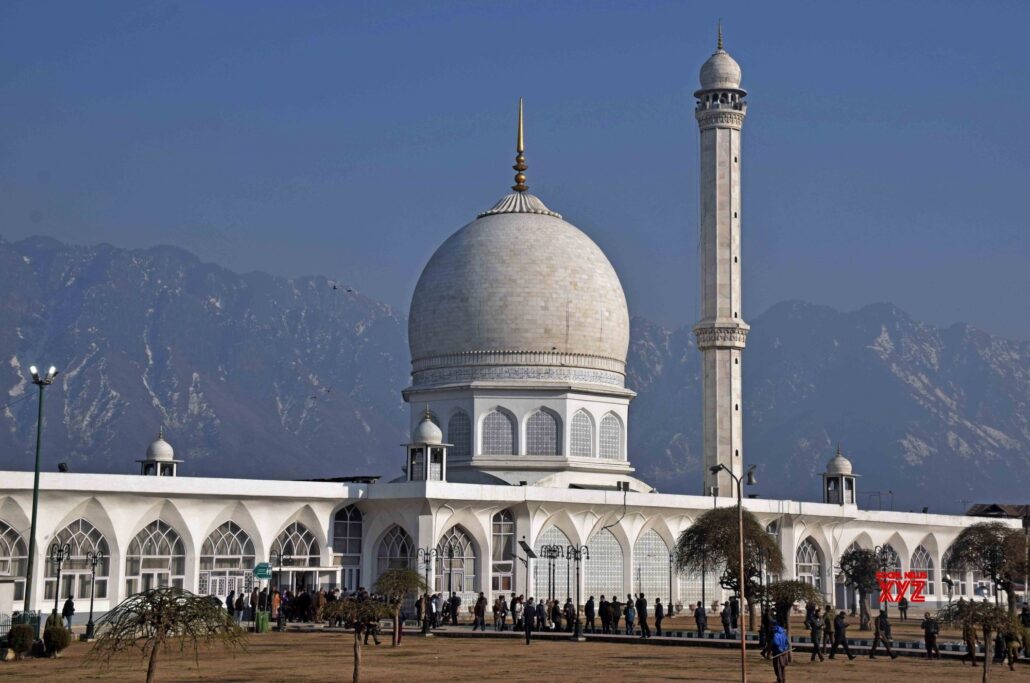

Situated on the banks of Dal Lake, framed by the snow-clad peaks of the Zabarwan Range, the Hazratbal Khanqah stands as the most revered spiritual site in Kashmir. Known for housing the Moi-e-Muqadas—the holy relic of the Prophet Muhammad—the Khanqah is not only a religious center, but a monument to faith, resilience, and the intersection of spirituality and politics in Kashmir.

ALSO READ: Khanqahs, sultans and the state: The detailed history of Waqf in Kashmir

The roots of Hazratbal lie deep in the Mughal era, when the site served as Ishrat Mahal, a pleasure garden built during Emperor Shah Jahan’s time. The turning point came in 1699, when the Moi-e-Muqadas arrived in Kashmir. Its presence transformed the location into a sanctuary of immense spiritual power. Amid growing public devotion, the site evolved organically into a shrine. Over the centuries, it became the custodian of Kashmiri Muslim identity.

Historically, Kashmir’s religious shrines—known as khanqahs, were managed through hereditary custodians (mutawallis), in keeping with Sufi traditions. Khanqahs such as Khanqah-e-Moula, Makhdoom Sahib, and Charar-e-Sharif operated under local and familial authority, but that changed during the Dogra rule (1846–1947).

The state began asserting control over high-revenue shrines, leading to tension with the Muslim community. From the 1930s onward, efforts began to formally register waqf properties.

By the early 1930s, Sheikh Muhammad Abdullah led Muslim Conference advocated for a unified endowment structure run by the people. This vision took form with the establishment of the Muslim Auqaf Trust (MAT), even as Sheikh remained imprisoned under the Kashmir Conspiracy Case post 1953.

Once functional, the MAT began acquiring custodianship of Kashmir’s major Khanqah, none more significant than Hazratbal.

The idea of reconstructing Hazratbal first emerged in 1967, during Sheikh Abdullah’s meeting with Habibur Rahman, then the Government of India’s head of construction.

Despite enthusiasm, a major challenge loomed: funding. With all available land already consolidated by the Auqaf, Sheikh turned to the people of Kashmir. In his autobiography Aatash-e-Chinar, he recounts visiting neighborhoods, collecting donations from pilgrims and devotees across cities and villages.

Sheikh Mohammed Abdullah himself travelled into the farthest corners of Kashmir to gather money for the Dargah. One of the most remarkable stories about the Srinagar city. Sheikh Abdullah went to Habba Kadal and a counter was installed for donations. An old woman came and Sheikh asked what she had brought for the donation. “I have nothing Sheikh sahab, but these few utensils of copper and almunium, but i want this money to be used for the Dargah too.” Sheikh burst into tears.

“Praise be to God, this campaign continued righteously… people from Srinagar and beyond contributed generously,” Sheikh writes in Aatash e Chinar.

The final cost exceeded one crore rupees, a substantial amount in the 1970s, entirely raised through public contributions. This massive public investment covered not only construction but also high-quality craftsmanship and imported materials, reflecting the community’s spiritual commitment.

At the heart of the Dargah’s architectural transformation was M.M. Fayyazuddin, a renowned architect from Hyderabad, India. Fayyazuddin broke away from Kashmir’s traditional wooden-pagoda architecture, typically influenced by Buddhist and Tibetan styles—to introduce a clean and elegant design rooted in classical Islamic aesthetics. His blueprint brought grand domes, arched corridors, and finely proportioned minarets into a landscape where such features had been largely absent.

The mosque was built using Makrana marble, sourced from Rajasthan, the same quarry that supplied marble for the Taj Mahal. Its choice imbued Hazratbal with a sense of continuity with South Asia’s most iconic Islamic monuments.

The interior, meanwhile, retained local sensibilities, including beautifully carved walnut woodwork, ensuring that the shrine remained rooted in Kashmiri craftsmanship.

Complementing the architectural design was the Arabic calligraphy that graces the chamber housing the relic. Executed by master calligraphers from Lahore (Pakistan) and Delhi (India), the work drew inspiration from Ottoman and Persian styles, transforming the shrine into a sanctuary of spiritual and visual harmony. Their artistry gave Hazratbal a textual and sacred presence that evoked the deep lineage of Islamic devotional spaces.

One of the most striking additions was a massive chandelier imported from Czechoslovakia (modern-day Czech Republic and Slovakia), one of the largest in the world at that time. This grand fixture, the largest of its kind in Kashmir at the time, hangs above the central hall, casting soft light over the sacred relic and symbolizing divine radiance in a space of profound reverence.

While the reconstruction was widely celebrated, it also drew sharp political criticism. Right-wing publications such as the RSS’s Organizer accused Sheikh Abdullah of creating a “Muslim Vatican” in Srinagar. Politicians in New Delhi argued that the Khanqah was becoming a symbol of separatist assertion. In response, Sheikh defended the Dargah as a spiritual and social project, not a political one.

“The purpose was never political posturing,” he wrote during his imprisonment. “I envisioned a space where the soul of the people could find healing, center for spiritual awakening, education, and service.”

Following the Indira-Sheikh Accord of 1975, Sheikh returned as Chief Minister. He reasserted control over the Auqaf Trust, expanded its reach, and directed its income toward social reform. In the years that followed, the trust grew to manage over 1,200 properties, including schools, hospitals, orchards, and agricultural estates.

Today, Hazratbal is more than a monument—it is a living history. Its gleaming white dome, floating in the reflection of Dal Lake, reminds every visitor that Hazratbal is not just a building—it is Kashmir’s spiritual heartbeat.

The Author is a historian from Srinagar. Witness to several political and religious developments in Kashmir, the author has decades of expertise in writing on historical subjects.