On July 9, 2022, thousands of Sri Lankans stormed the presidential residence in Colombo. They swam in the pool, reclined on the gilded chairs, and, most tellingly, cooked in the presidential kitchen. The images were consumed as spectacle around the world, but their meaning ran far deeper than theater. Citizens who had endured months of empty shelves and endless fuel queues were reclaiming the most ordinary sites of survival. The kitchen, usually a private corner of family life, had been transformed into the first battleground of politics. That occupation was not only about the Rajapaksas. It marked the unraveling of a system that treated the poor as disposable while insulating elites from the consequences of their decisions.

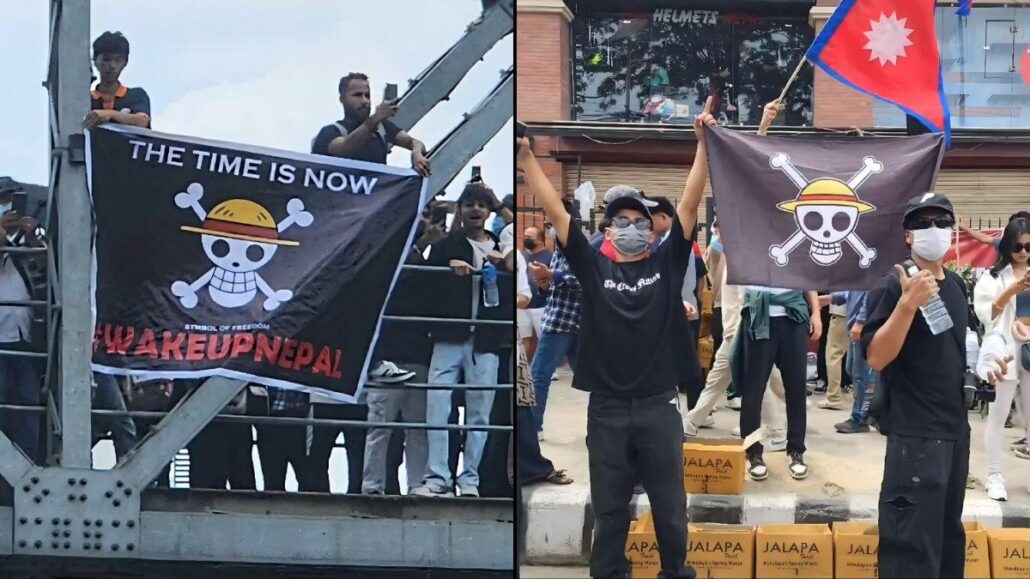

This drama in Colombo did not stand alone. Across Asia and Africa similar ruptures appeared: the Aragalaya movement in Sri Lanka, the Nepo Kids demonstrations in Kathmandu, tax revolts in Nairobi, and the Monsoon Uprising in Dhaka. At first glance each protest has its local trigger and its own narrative, but under the surface a common logic appears. These are not events sprung from isolated failures. They are the visible outcomes of political economies that, over decades, concentrated power and privilege in a narrow circle and managed the masses with symbolic gestures rather than substantive redistribution. What the streets show is not mere political change but the erosion of whole orders of governance.

Mainstream media found it convenient to brand these uprisings as youth revolts. Camera crews lingered on witty placards in Kathmandu, live streams proliferated from Nairobi, and snippets of poolside spectacle in Colombo spread across feeds. That framing suits television markets and social media attention economies because it makes the story easily digestible. But it also flattens the struggle. Behind every viral chant lies a household bargaining for food, a wage earner stranded by fuel shortages, a graduate whose diploma opens no door. The aesthetics of protest are real, but they are the surface of a deeper class confrontation over who will shoulder the costs of economic crisis and who will remain protected.

Sri Lanka makes the stakes clear. At the height of its crisis inflation crossed fifty percent, food inflation soared beyond ninety percent, and more than twenty percent of the population fell below the poverty line. Hospitals lacked basic medicines, schools closed when buses could not be fueled, and the World Bank estimated millions were pushed into poverty within a single year. Jude Fernando, writing in SAGE Journals, insists the Aragalaya was not merely a reaction to incompetence or dictatorship but a response to “racial capitalism.” Food and fuel shortages were the immediate sparks, but the fuel for the conflagration had been accumulating in governance structures steeped in nepotism and patronage. The Rajapaksas became the public face of a deeper capture. As Fernando argues, the movement amounted to “a political revolution,” not in the narrow sense of replacing leaders but in the wider sense of questioning the structure of rule itself.

Fernando’s diagnosis echoes a central insight of Marx. Crises under capitalist forms of accumulation are not aberrations. They are expressions of a system that concentrates wealth in one place while generating deprivation elsewhere. Marx’s observation that accumulation at one pole is accumulation of misery at the opposite pole is visible in Sri Lanka’s queues and empty pharmacy shelves. When the state functions as a patronage machine and policy serves elite networks, shortages stop being anomalies and become structural features. The seizure of the palace kitchen was therefore a moral and political indictment: politics had become an instrument of elite reproduction and could not pause the hunger it helped create.

Bangladesh must be read in the same register. The Monsoon Uprising of July 2024 began as an explosive reaction to state failure during catastrophic floods, but it widened into a critique of governance that mixes symbolic policy with elite capture. Research on the uprising has shown how Facebook played a decisive role in shaping collective identity and mobilizing communities, yet the social media dimension masks a deeper story: households suffered from rising staple prices and from relief systems that failed to reach the most vulnerable. Elsewhere in 2024 student protests over the public service quota system revealed a related fault line. The quota reserved a visible share of government jobs for descendants of the 1971 liberation war.

To graduates locked out of formal employment that quota became a symbol of inherited privilege. The demonstrations were therefore not merely procedural arguments about hiring rules. They articulated a wider grievance. For young people and for those from modest backgrounds the quota represented a political economy in which lineage and connection purchased access to security while ordinary citizens received token gestures.

Read together the Monsoon Uprising and the quota movement show how symbolic policies and real deprivation interact. Governments can stage development projects and celebrate GDP growth while everyday life moves in the opposite direction. That gap produces rage because it reveals policy as theater. When relief is delayed and basic food becomes scarce the spectacle of development becomes obscene. The Bangladesh experience therefore complements Fernando’s claim about Sri Lanka. Both countries show how elite privileges and patronage subvert the social contract, and both show how protests named by the media as youth rebellions are actually claims for material protection and political inclusion.

Nepal’s protests followed a similar pattern. The chants of “Nepo Kids” signaled cultural mockery, but the feeling behind the slogan was political. The country has long depended on remittances that at times amount to more than a quarter of national income.

The state boasts of roads and projects, but youth unemployment hovers near nineteen percent and economic growth translates poorly into jobs. Inflation averaged between six and seven percent in recent years and food prices consistently rose faster than the general index. For a large cohort of young men and women the imagined ladder of development stops at precarity, migration, or casual work. The protests were mediated by viral culture, yes, but their content was the alienation Marx described: a generation cut off from meaningful labor and from a share in the benefits the state claimed to deliver.

Kenya completes this comparative picture by showing how policy design itself can turn into a provocation. The Finance Bill proposed in 2023 sought new revenues by taxing bread, cooking oil, fuel, and digital services. For citizen households already coping with inflation near eight percent and food inflation above thirteen percent the proposed measures were not abstract fiscal choices. They threatened immediate hunger. With more than a third of the population living in poverty, taxation that bites first the stomach is experienced as predatory.

Cooking gas prices jumped by nearly thirty percent in a year and bread in many places became harder to afford. Popular resistance turned into a movement not because youth were fashionable but because civic life had been converted into arithmetic that households could not absorb. In this case the mechanics of adjustment were explicit. The state sought to meet external fiscal demands and to placate investors while shifting the burden onto the poor. That is extraction in practice.

What unites Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Nepal, and Kenya is the same structural arrangement. Each polity relied on elite dominance and distribution through networks rather than through universal institutions. Each filled the language of governance with rhetorical development while failing to secure basic livelihoods for large swathes of the population. Each substituted symbolic policies for structural redistribution. And each assumed the suffering of the poor could remain an invisible background. That assumption is what these movements have refuted.

The collapse is therefore not simply political turnover. Changing a president or passing a law does not by itself repair a political economy in which state resources and opportunities are canalized to a connected few. When systems of rule normalize exclusion, their legitimacy erodes. Fernando’s description of racial capitalism helps to name one mechanism. It shows how hierarchy, ethnicity, and political networks can compound global pressures and local corruption into regimes that produce scarcity. Marx explains why such regimes are unstable. When accumulation concentrates wealth and disposes others to insecurity the excluded will not remain silent. They will make politics out of survival.

These protests also teach an important lesson about media and narrative. Labeling complex social struggles as youth movements or digital spectacles is not neutral. It is an act of misdirection. The spectacle obscures the daily arithmetic of survival: an increase in the price of cooking oil, a fuel queue that prevents commuting, a lost contract that ends a livelihood. Understanding these uprisings requires paying attention to those basics. It also requires a willingness to question policies that prioritize fiscal optics over social protection, that value headline projects over functioning hospitals and reliable transport.

If the French Revolution began with bread and the Russian Revolution with calls for peace, land, and bread, then the contemporary protests return us to that elemental logic. Revolutions and upheaval are seldom born of abstract theory alone. They begin in kitchens, in markets, and on the morning commute. When the state can no longer assure the material foundations of life, the social compact fractures. The world watching these events should take this as a warning. Inequality, climate stress, commodity shocks, and predatory policy converge in many regions. Where political orders are built on privilege and theatrical policy they will be brittle under pressure.

These movements thus demand a different response than a simple change of leadership. They require institutional re engineering and a reordering of priorities. Policies that deliver secure food, reliable transport, universal health coverage, and decent work matter more than symbolic programs or prestige projects. State legitimacy will be rebuilt only by embedding redistribution and accountability into the routines of governance rather than by occasional gestures.

The protests from Colombo to Dhaka to Kathmandu to Nairobi insist, in their own forms, on a more basic proposition: that politics must begin with the common man and remain inclusive. Roads, flyovers, and prestige projects cannot substitute for affordable food, reliable electricity, and secure work. No matter how heavily governments invest in spectacle, or how much the media tries to sell images of progress, the emptiness of these promises is revealed in every market stall where prices outstrip wages and in every household forced to choose between fuel and food.