1846–Gulab Singh’s rise to power in Kashmir marked a pivotal moment in the valley’s history. The era was characterized by privatizing land and the consolidation of autocratic rule. Gulab Singh’s policies transformed agrarian societies into tenants on their ancestral lands, laying the groundwork for socio-economic disparities and cultural suppression.

During his successor Ranbir Singh’s reign, religious tensions escalated with the prohibition of new mosque constructions in Kashmir. Ranbir Singh’s policies exacerbated religious and cultural sensitivities among Kashmir’s Muslim majority population~ Chitralekha Zutshi, in Kashmir: Convoluted Histories.

The anti-Dogra resistance movements in Kashmir found sporadic but passionate expression. The defiance of 1924, particularly the construction of a mosque at Sherbagh, Anantnag, despite prohibitive laws, is noted in Kashmir: A Disputed Legacy, 1846-1990 by Alastair Lamb, emphasizing how these acts of defiance reflected simmering discontent and resistance against Dogra autocracy.

One of the most significant challenges faced by Kashmiris under the autocratic rule was agrarian exploitation and land tenure policies that entrenched socio-economic inequality. The land policies initiated by rulers like Gulab Singh and continued by successors such as Ranbir Singh favored a feudal system where a small elite class owned vast tracts of land, while the majority of Kashmiri peasants were reduced to tenants on their own ancestral lands.

This system perpetuated economic disparities, disenfranchised the peasantry, and entrenched a cycle of poverty and dependency, setting the stage for widespread discontent and resistance movements in later years. Economically and politically, Kashmiris of this era faced profound challenges, as written by Tariq Ali in Kashmir: The Case for Freedom.

In 1931, tensions in Kashmir reached a critical juncture due to oppressive Dogra policies. The burning of the Quran in Jammu on May 29, 1931, by the state administration sparked widespread outrage among the Muslim community, symbolizing religious desecration and intensifying communal tensions. Subsequently, on July 12, 1931, the Maharaja’s administration barred Eid prayers in certain areas, a move seen as a direct infringement on religious freedoms and a catalyst for mounting public discontent.

Enter Abdul Qadeer

The year 1931 marked a pivotal beginning of a significant chapter in Kashmir’s struggle for autonomy and political rights and from the 1931 uprising emerged a handful of leaders and heroes and one of them was Abdul Qadeer Khan.

Abdul Qadeer, an employee of a British army officer, emerged as a significant figure in the 1931 movement against the oppressive Dogra rule in Kashmir. Qadeer, originally identified as a butler to a European officer rose to prominence during a meeting where he spoke out against the government’s brutalities. His speech, delivered with emotional intensity, marked the climax of the day’s events . Notably, Qadeer was a disciple of Jamaluddin Afghani, a renowned Muslim philosopher who had visited Kashmir prior to his departure to Russia (Hussnain, Greater Kashmir, 2007) .

According to Pandit Bazaz, Qadeer had previously met Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah at Jamia Masjid, expressing his admiration for Abdullah’s speeches and requesting an opportunity to speak to his fellow Muslims (Saraf, I: 373-4) . On June 25, 1931, Qadeer delivered a powerful speech, urging the people to “rely on your own strength and wage a relentless war against oppression” and even called for the destruction of the Maharaja’s palace: “Raze it to the ground” (Para, 118) , but he was arrested and charged under sections 124-A (treason) and 153 of the Penal Code.

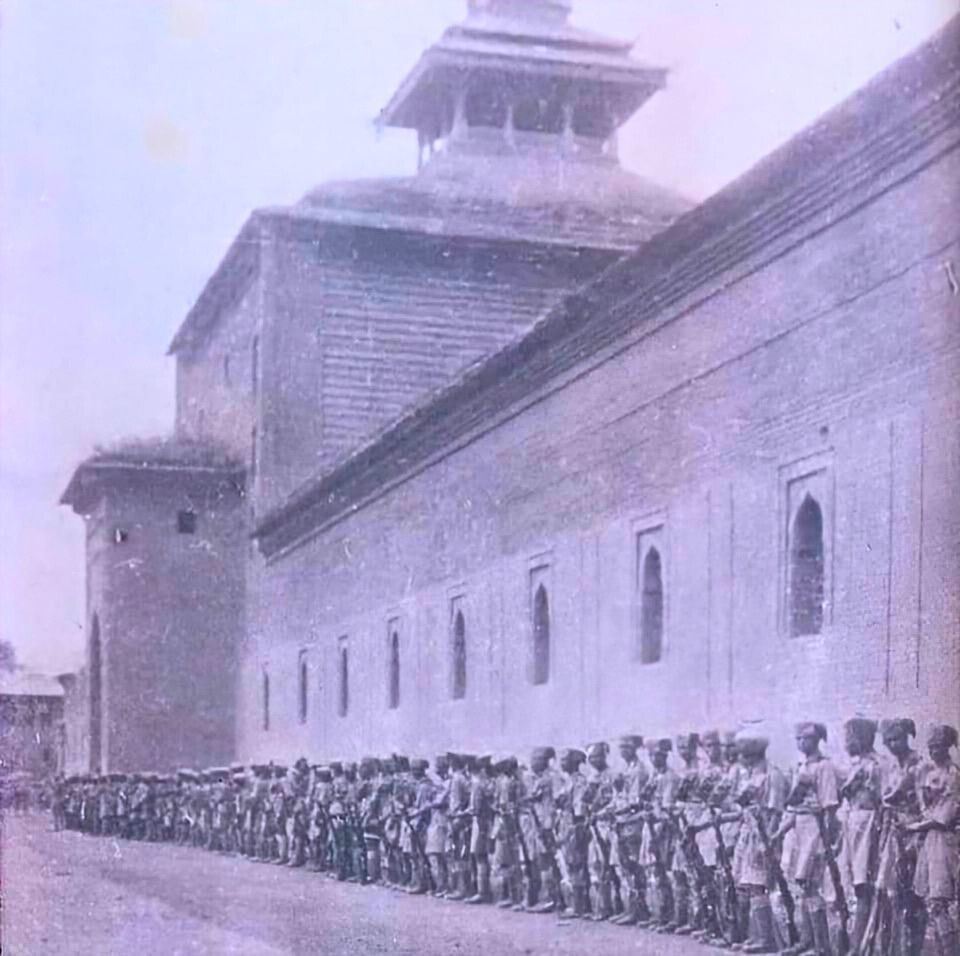

During his trial, which began on July 6, the court proceedings attracted significant attention. The Chief Justice observed that the trial had greatly excited the Muslim public opinion, leading to large crowds assembling in and around the court premises. The District Magistrate suggested holding the trial in the jail due to the massive turnout, which was granted, with 100 policemen forming the guard (Saraf, I: 380) .

The Chief Justice held:

“Abdul Qadeer was arrested on the 25th of June. During four hearings in the Court of Sessions on the 6th, 7th, 8th, and 9th (July) it was found that the trial had greatly excited the Mohammadan public opinion and crowds of Mohammadans obstructed traffic on the way while the prisoner was brought to the Court and taken back every time to the judicial lock-up. Large crowds assembled in the Court and Court compound also. On 11th July the District Magistrate, therefore, suggested that the trial should be held in the jail and the permission was granted. 100 policemen formed the Guard at the jail. As a rule 19 men are on duty at a time. When the Sessions Judge arrived for the trial at about 1 p.m. a crowd of 4 to 5 thousand Mohammadans had collected at the Jail, and transparently the Police force was entirely inadequate to over-awe such a crowd. The Sessions Judge has stated that it was related by the Jailor that the crowd wanted to enter the Jail building and to have a look at the face of the accused. There was not the permission given to the crowd. The total police force at that time consisted of 22 armed policemen and 119 other policemen. (Referring to the District Magistrate, the report says), it was his duty to question the mob, to find out what its object was and try to reason with it. This omission on the part of the D.M. has met with our disapprobation. He thereupon ordered that the rioters (rioters for having entered the compound without permission) may be arrested. As to the wisdom of such an order we have doubts. As soon as some members of the crowd were arrested and five of them brought in, there happened what should have been predicted. The crowd grew restive and proceeded to throw stones. According to the Governor (D.M.), he gave orders which resulted in firing eleven times.”

Abdul Qadeer was deported from the State immediately after completing his sentence of six months.

The Aftermath of July 13

The victims had gathered to witness Abdul Qadeer’s trial, sparking massive public resentment and the organized movement against Dogra rule. Dr. Ghulam Hassan Khan, in his book “Freedom Movement in Kashmir (1931–1940),” describes July 1931 as the beginning of an organized struggle by Kashmiri Muslims against autocracy, marking the end of more than eight decades of suffering .

A day after the 13 July bloodshed, Maharaja Hari Singh appointed an enquiry commission under Barjor Dalal, Chief Justice of ‘His Highness’ High Court, with two judges of the court and a non-official Muslim and Hindu each as commissioners. The commission was tasked with enquiring and reporting upon “the circumstances which led to the recent disturbances” and to identify the factors that had incited the Muslim populace.

Pandit Aftab Kar, Head Master of Anglo Vernacular Primary School in Vicharnag, testified before the commission. He reported that he was beaten and his clothes were torn by ‘Muslim rioters’ but also acknowledged that “some Muslims treated him well.”

On July 16, Sutherland and Wakfield visited Vicharnag. In his statement to the Enquiry Committee, Sutherland highlighted a significant point. He mentioned that during their visit to Vicharnag, not a single Hindu complained about their house being looted. He told the committee that if the Hindus had experienced looting, they would have certainly reported it to him and Wakfield.

Columnist Abdul Majid Zargar argued that there was no major incident or ‘rioting’ at Maharajgunj on July 13. He claimed that a minor clash occurred between Muslims who had gone to buy white cloth for shrouds for the dead and Punjabi Hindu traders who sold cloth wholesale. The clash was triggered by a trader making ‘obscene and uncalled for remarks,’ leading to an argument and subsequent altercation.

Gwasha Lal, a Kashmiri Pandit ‘journalist,’ deposed against Iqbal before the Riots Enquiry Committee, accusing him of conspiring to overthrow Maharaja Hari Singh. Lal’s statement was widely circulated by the Hindu Press, claiming he had attended a meeting at Dr. Iqbal’s residence where suggestions to overthrow the Kashmir Government were discussed. This narrative was later discredited as fabricated.

The Milap, a newspaper, lamented the release of Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah and other leaders arrested after the July 13 incident. The newspaper warned that if the Government did not take immediate action, “the Hindu Government would be finished and the Hindus will either be forced to flee or be killed”【Saraf, I: 390】.

Jia Lal Kilam, a prominent Pandit leader, did not mention any loot or attacks on Pandit properties in his 1955 book, A History of Kashmiri Pandits. Historian Dr. Showkat Hussain stated that there was no communal violence, only demonstrations against the State and minor stoning of some Khatri shops in Maharajgunj after the firing incident outside the Central Jail.

Abdul Majid Zargar further elaborated that not a single Kashmiri Pandit was harmed during the July 13 events, emphasizing that claims of large-scale violence against Pandits were fabricated long after the incident occurred.

The narrative of widespread violence against Pandits on July 13, 1931, was further challenged by the absence of any such claims in documents like FIRs, complaints, or contemporary writings by Pandits between 1931 and 1947. (Saraf, I: 393)

The hostility of some Pandit leaders towards Sheikh Abdullah and his policies led to their resignation from the National Conference. They opposed the raising of slogans like ‘Naar-e-Takbeer’ and the recitation of Qur’anic verses in public meetings, which Abdullah defended as an expression of the people’s sentiments.

In an interview published in Shabistan Digest Delhi and quoted by weekly Kashir Rawalpindi in its issue dated 29th July, 1970, Sheikh Abdullah said:

“I was attending a victim who told me in a fast fading voice: ‘Abdullah! I have done my duty. Now you proceed ahead.’ I did proceed ahead. Many an odds stood in the way but I surmounted them; so much so that the Premier, Pandit Hari Kishan Kaul, stood like a wall in my way. I was rearrested on 21st September; in the Jail, I was stripped completely naked and for 13 days I struggled between life and death but this did not dampen my spirits; my aspirations did not cool off; my enthusiasm did not fade away. When I was released on 3rd October, I was again in the midst of the movement. The words of the martyr were still ringing in my ears: ‘Abdullah! I have done my duty. Now you proceed ahead.’