Mohan Lal’s home in Kanthan-A once overlooked rolling hills, the winding Chenab River, and fields that had sustained his family for generations. Today, the world’s highest railway bridge dominates that view, a towering structure of steel and concrete. Instead of bringing prosperity, the bridge has left his village cut off, his fields dry, and his future uncertain.

“They took our land, blocked our water, and now we watch the trains pass by, knowing we will never be part of this progress,” he says.

The villages of Bakkal and Kauri, nestled on either side of the Chenab River, are now etched into history because of the bridge that connects them.

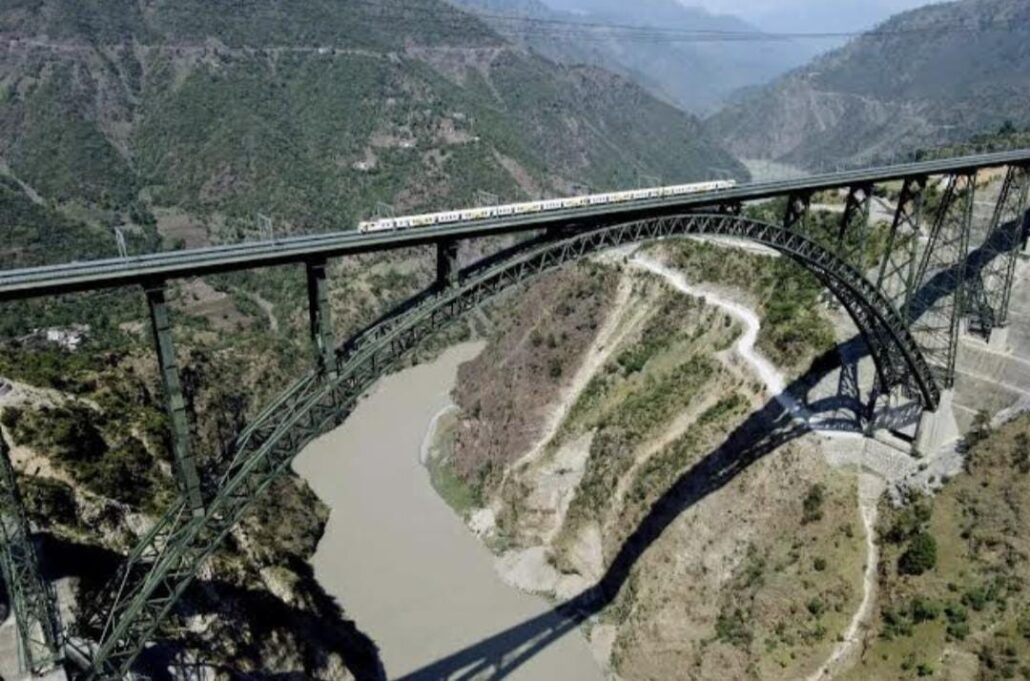

This bridge, standing 359 meters above the riverbed and stretching 1,315 meters in total, is a critical part of the Udhampur-Srinagar-Baramulla Railway Link, which was designed to connect Kashmir to the rest of India. The hope was that it would bring prosperity, employment, and tourism to these remote border villages. Yet the reality for the people living here is far different.

Bakkal, home to around 2,500 to 3,000 residents, was once a thriving agricultural community, with fertile land fed by the river. However, the construction of the bridge brought a dramatic shift. “The water sources dried up after the construction, and our fields became barren,” said Amarnath, a local resident.

With no water to irrigate their crops and no jobs to replace the lost agricultural income, many families were forced to migrate to other areas in search of a better life.

The promise of tourism never materialized. Heavy security restrictions were imposed on the area, keeping both tourists and locals at a distance from the bridge. Amarnath voiced the frustration felt by many villagers: “We can’t even cross the bridge on foot to visit our relatives. This bridge that was supposed to connect us to the world has only divided us further.”

In the past, the community had hoped for employment during the construction phase of the project. But once the project was completed and the construction company left, all that remained was the stark reality of unemployment and despair.

Across the river in Kauri, in the Kanthan-A Panchayat of the Arnas block, the situation is no better. Mohan Lal, a local resident, explained how their lands were swallowed up by the construction without any compensation.

“We lost several kanals of land to the railway project, but we haven’t received a single penny from the railways,” he said. The once-thriving agricultural community now faces significant hardship. With no other industries or sources of employment, villagers have been forced to seek work far from home

The story of migration is deeply felt here. People who once lived off the land have been forced to leave their ancestral homes in search of work. “Our youth will have to leave for Reasi or other areas to earn a livelihood,” said Sansar Singh, a former Sarpanch from the Kanthan-B Panchayat.

This isn’t the first time the community has suffered due to large-scale projects. They had already lost land years ago to the Salal Hydroelectric Power Project. Now, the railway line has claimed even more of their land, and the villagers have received nothing in return.

Adding to their frustration is the lack of infrastructure to make use of the bridge. A two-platform railway station was built in Bakkal, but it won’t serve the local population once train services begin. The Vande Bharat trains, which are set to operate on the line, won’t stop in Bakkal, forcing villagers to travel more than 40 kilometers to the nearest station in Katra.

“The distance between us has increased, not decreased,” said Mohan Lal. What was once a mere 1.3-kilometer gap across the river now takes over two hours to traverse, as people are forced to rely on outdated roads and risky crossings. No footbridge or motorable bridge has been constructed to make it easier for families to visit each other.

Even though the villages were hoping for a brighter future with the railway link, they have been left with nothing but broken promises. While the bridge has gained international recognition, the people of Bakkal and Kauri are left grappling with the harsh consequences of this so-called progress.

The Chenab Railway Bridge, which was meant to bring development, has only brought misery to these border villages. The once-thriving agricultural land is now barren, people have lost their homes, their jobs, and their water sources, and migration has become the only way to survive.

The bridge that was supposed to connect communities has instead left them more isolated, struggling to cope with the unintended consequences of development. (With inputs from ETV)