In ‘The Chief Minister and the Spy,’ former RAW chief A.S. Dulat revisits the controversial 1987 Jammu Kashmir Assembly elections—a moment widely seen as a turning point in the region’s political trajectory, one that ultimately sowed the seeds of insurgency.

The book sheds fresh light on how the Congress-led central government allegedly manipulated the electoral process to retain “Delhi’s control over Kashmir.”

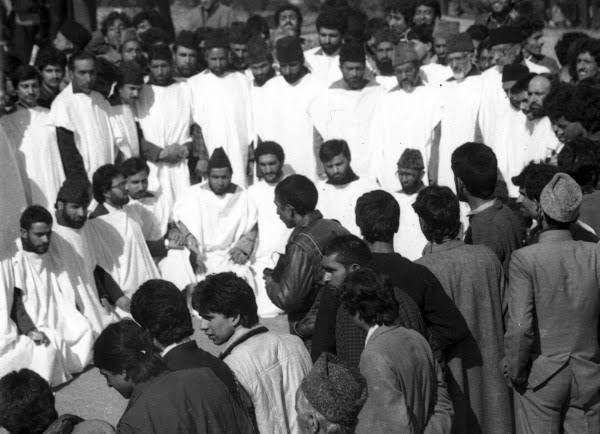

Held on March 23, 1987—just four months after Farooq Abdullah’s return as Chief Minister through a Congress-NC alliance—the elections featured a formidable challenge from the newly formed Muslim United Front (MUF), a coalition of various socio-religious groups. Turnout across the Valley was massive, reflecting a rare moment of electoral enthusiasm.

Dulat, in his book, points out that one of the most glaring episodes in the rigging debate was in the Amira Kadal constituency, where MUF candidate Sayeed Salahuddin was visibly leading. His rival from the NC, Ghulam Mohiuddin Shah, reportedly left the counting centre disappointed, only to return later as the declared winner by a margin of 4,289 votes. “Protests erupted immediately, triggering curfews in several districts and the arrest of MUF leaders including Salahuddin and Yasin Malik,” Dulat writes.

Dulat writes that these elections were “reportedly rigged to prevent Delhi from losing control of Kashmir.” Yet, the Election Commission did not act on complaints or allegations of fraud, further implicating institutional complicity. According to widespread belief and subsequent political commentary, the Congress-led central government was seen as orchestrating the rigging in collaboration with regional powerbrokers.

Farooq Abdullah, as per Dulat, distanced himself from the accusations. When confronted by journalist Harinder Baweja, he lashed out: “Rigged election, my foot. I don’t believe it… It is India that is responsible for what has happened in Kashmir and not Farooq Abdullah. They betrayed my father in 1953. They betrayed my father in 1975. They betrayed me in 1984. They are responsible.”

“Even years later, Abdullah’s opponents continue to hold him accountable, though he has consistently argued that any electoral manipulation was carried out at the Centre’s behest,” Dulat writes.

Interestingly, when Dulat assumed his official post in Kashmir in May 1988, he found no internal acknowledgment of the rigging. Instead, many officials—local and deputed—spoke highly of Abdullah, he recalls. Former DGP Francis T.R. Colaso, who served during the 1986–87 period, downplayed the rigging. He told Dulat that if rigging occurred at all, it was limited to a few constituencies and blamed “Kashmiri bureaucrats, more loyal than the king,” for it.

Dulat’s account doesn’t offer final answers, but it does revive questions about how electoral subversion in Kashmir fueled decades of disillusionment—and eventually, armed militancy.