Shah Shahid

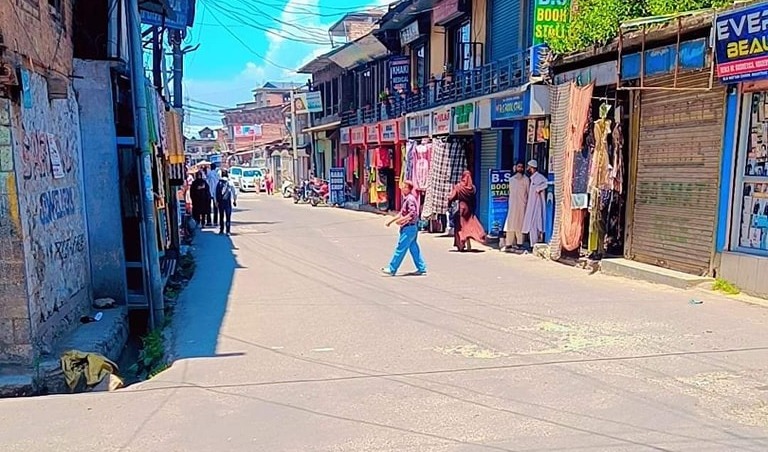

In the days before Eid, Srinagar’s markets—Lal Chowk, Goni Khan, Maharaj Bazaar—are usually flooded with people. Shoppers jostle through narrow lanes, buying everything from clothing to dry fruit. But this year, something is different. The crowds are thin. Many shopkeepers say this is the slowest Eid season they’ve seen in years.

Why?

The answer lies far beyond Srinagar, in the rural belt of Kashmir—especially in its orchards and farmlands. From Shopian to Baramulla, the backbone of Kashmir’s economy is agriculture. According to the Directorate of Economics and Statistics (JK), around 70% of Kashmir’s population is directly or indirectly dependent on agriculture and horticulture. This includes those who grow apples, walnuts, rice, vegetables—and those involved in packaging, transport, and trade.

But over the past few years, and especially in 2023–25, these farmers have been hit by repeated crises.

One crisis after another

In late April, a hailstorm damaged crops in south Kashmir. And then, on June 1, just days before Eid, another severe hailstorm hit Shopian, damaging 90–100% of the apple crop in at least 14 villages, including Dachoo, Chitragam, Hushainpora, and Gund Darvesh. Photos from these areas show battered trees, fallen fruit, and branches stripped bare. “This year’s entire effort is wasted,” said one orchardist. “There is nothing to sell.”

This is not an isolated event. Over the past few years, farmers in Kashmir have faced repeated setbacks. The lockdown from 2019 to 2021, along with post-Article 370 transport disruptions, led to apple boxes rotting at fruit mandis due to delays. The influx of cheap Iranian apples in Indian markets further slashed prices for Kashmiri growers. At the same time, the cost of inputs—fertilizer, pesticides, labour, and packaging—has surged by 20–30% in just two years. Many farmers also report receiving poor-quality pesticides that fail to protect crops against scab and pests, resulting in reduced yields.

With crops damaged and income lost, rural families have little to spend during Eid. And that’s where the urban impact begins.

Ghulam Hassan Dar, once an orchardist, now spends his days in Himachal trading shawls and Kashmiri garments—a far cry from the life he once knew. “I used to shop for my entire family, for the kids, buying what they needed without worry,” he shared quietly. “But in 2023, I was forced to sell my land and turn it into a brick kiln. Farmers don’t want to do this, but they have no choice. Now, I don’t even go to Anantnag for shopping anymore. I simply don’t have enough.”

His words echo the heartbreak of many in Kashmir’s rural communities—once proud cultivators, now struggling to hold on to their livelihoods amid relentless crisis.

Understanding the economic chain

When farmers face crop losses, their income goes down. With less money in hand, they reduce spending on essentials and non-essentials alike—fewer clothes, fewer gifts, and less meat or sweets during Eid. In Kashmir, where rural income plays a major role in driving urban markets, this shrinkage in rural spending results in lower demand in cities. Shopkeepers sell less, roadside vendors earn less, and the overall buzz of commerce fades. Eventually, the entire local market slows down.

In economic terms, this follows a classic Keynesian demand-side chain:

Agricultural loss → Lower rural income → Lower consumer spending → Weak urban demand → Market contraction.

In simplistic terms; When farmers lose crops—due to hailstorms, pests, or poor market prices—they earn less money. Since most of Kashmir’s rural population depends on farming or orchard work, a failed harvest means less income for entire villages.

With reduced income, people naturally cut down on spending. They buy fewer clothes, gifts, or food items, especially during festivals like Eid. Instead of shopping in town, they try to save money, postpone purchases, or avoid non-essential items altogether.

This decline in rural spending directly affects urban markets like Srinagar, Anantnag, and Baramulla, where most shopping occurs. When rural customers don’t show up, these markets see fewer buyers. Shopkeepers, vendors, and service providers earn less because demand has fallen.

When city businesses sell less, they cut costs—sometimes laying off workers, reducing inventory, or shutting down early. This triggers a slowdown across the entire local economy. Less income leads to less spending, which leads to even less income, creating a vicious cycle.

In simple terms: if farmers don’t earn, they can’t spend. If they don’t spend, shopkeepers don’t earn. If shopkeepers don’t earn, markets shrink—and the whole economy slows down. This is how a rural crisis becomes an urban problem. It’s a clear example of how agriculture drives local demand in regions like Kashmir.

Meanwhile, the urban class—those salaried or self-employed—have shifted to online shopping, bypassing the local economy altogether. The informal vendors, shopkeepers, and seasonal traders who depend on Eid sales are feeling the pinch.

For rural Kashmiris, online purchases aren’t even an option—most lack stable income, let alone credit cards or reliable logistics. The crisis they face today is not just economic but deeply emotional. In districts like Shopian, families are selling small portions of land to repay debts or cover urgent medical expenses. Many are pulling their children out of private schools as they struggle to cope with shrinking incomes.

In villages such as Zainapora and Sedow, young people are giving up orchard work altogether. “There’s no future in farming anymore,” said a former apple grower who now works as a bus conductor in Jammu. Others have taken up low-paying jobs in transport, security, or migrated to Delhi as labourers. Farming, for many, is no longer viable.

Despite repeated pleas, government support remains minimal. Crop insurance, where available, is slow and often covers only a fraction of the loss. Compensation for hailstorms is delayed or inadequate. Most critically, there is no Minimum Support Price (MSP) for fruit in Kashmir—leaving orchardists at the mercy of fluctuating markets and powerful buyers. “Without MSP, we’re gambling with our livelihoods every season,” one farmer said.

This erosion of rural income is not isolated. It drags down the entire regional economy. When farmers earn less, they spend less—especially on non-essentials. This decline in rural demand directly affects urban markets. In the lead-up to Eid, Srinagar’s bazaars were unusually quiet. “We were expecting a rush,” said a trader in Lal Chowk. “But customers aren’t coming. Maybe they have no money. Maybe they’re just not in the mood.”

This silence speaks volumes. The economic chain—from producer to consumer to seller—is broken. And the gap is only widening.

Underlying this economic distress is a worsening climate crisis. Shopian’s hailstorm is just one example in a pattern of extreme weather events battering the region. Erratic snowfall, unseasonal rains, and pest outbreaks have become more frequent. Meanwhile, deforestation, wetland encroachments, and unsustainable land use have only amplified the damage. “It’s not just nature turning against us—we’ve left ourselves exposed,” said an environmentalist in Pulwama.

The reality in Kashmir today isn’t just about supply and demand. It’s about cycles—of debt, displacement, and disconnection between rural producers and urban markets. Without structural intervention—climate-resilient agriculture, direct income support, and protective pricing—this fracture will deepen.

This Eid, the quiet in Srinagar isn’t just a mood. It’s a signal: if Kashmir’s farmers don’t recover, neither will its cities.