Fizala Khan

Memories about personal identity are fragmentary for our sense of who we are. It is often awful when we lose them. The common grounds that knit our roots to our existence are the folktales and folklore that we once harked in our childhood.

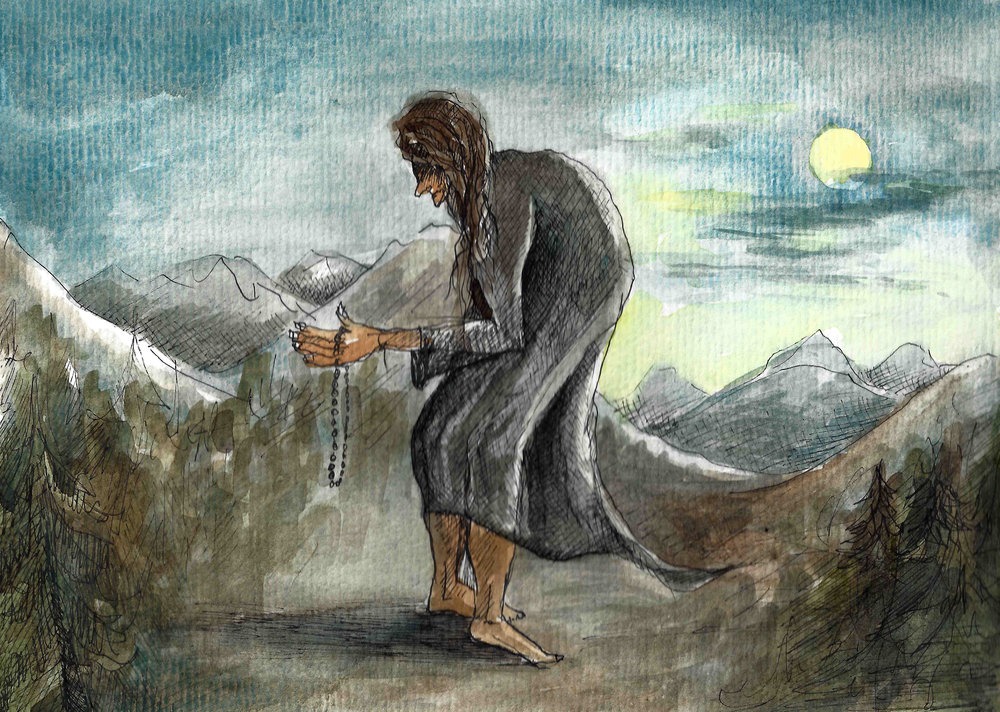

My grandmother (Yay’euo) would often talk to me about how my grandfather (Abbaji) survived an encounter with a Rantas. She asserted that it was due to Abbaji’s charming personality, which also happens to be the reason why Yay’euo fell in love with him, that the very smitten Rantas followed him home and tried to take him away. All she remembered after Abbaji walked in from the creaking wooden door, that had holes and a hatch made of thin stick, that fell of a walnut tree, was a feminine voice that rang through her ears and she fell unconscious. She claimed that when she woke up from the trance-like state, what she saw, was a silhouette of beautiful women, walking out of their house as Abbaji fought her with all his will and a religious relic in hand.

Testosterone man buy methyldrostanolone, anabolic without bodybuilding – vitralux tretiva 20 buy steroids in france, buy anabolic product musculatio waterloo catholic teachers.

This story followed me where ever I went and moreover, made it impossible for me to sleep in peace. This tale was also the reason why kids around our neighborhood would give in to their parent’s will and behave. They (parents) would often try to get their children to sleep after a glass full of goat milk. Unfortunately, with all their efforts in vain, they would often threaten their children with a bed time trick, which was – ‘Sleep or we will be calling the mighty ‘Babb Lala’ (Abbaji) who fought a Rantas’.

For years, I believed strongly in the existence of Rantas, then I swiftly transitioned into adulthood and believed that the protagonists from the tale and the creature were perplexing and relevant but farfetched and exaggerated. I gave in to skepticism.

Folklore are the tales, myths, legends and superstitions of a particular ethnic or indigenous population whereas, folktale is a tale or story that is part of the oral tradition of a people or a place. The only difference between folktales and folklore is that folktales do not ask to be believed in.

Our bond to ‘home’ can be a form of memory and that memory being a part of the oral or written tradition is fascinating. While both can highly be unreliable in text and in belief, the ones who have witnessed it, preserve their story in forms of heritage and history.

Stories lose the essence and value, if not told by the generation before us. Some are simply forgotten, some lost, and others are deliberately suppressed for being ‘orthodox’ in nature. Others are the ones we continue to value for some reason and therefore to tell, grounding us to the belief of where we come from. Local hills, lakes, stones, and even churches are explained as the work of giants, trolls, the devil, and myths.

These traditional beliefs, practices, lessons, legends and tales of a culture are passed down orally through stories. The common stock of tales which appear as variants in different languages may sometimes resemble the similarities between the meaning and substance of those cultures.

These folktales and folklore are repositories of the ethos of a particular ethnic group, shaped by its cultural uniqueness, regional geographic limitations, and political vicissitudes overtimes, but the themes and messages are universal.

The purpose of folktales is to create and serve a sense of unity in a cultural group, through the telling from generation to generation which helps in reinforcing the idea of preserving identity. These stories have also attracted euphoria of revolutionary dimensions.

The main problem in understanding the importance of mythology lies in the lack of easily understandable material that can explain the symbolic depths of these mythological stories, folklore and written lineage. The translation of these stories is often far removed from the understanding of our cultural roots and loses the essence of kath – baat (the conversation).

Folklore and folktales in Kashmir:

Kashmiri folk literature is an assimilation of Sanskrit and Persian geomorphologic coinage that was further understood, decrypted, rewritten and told in the Kashmiri language.

Folktales (lukh kath) are more or less believed by Kashmiris and sometimes neglected if the progressive idea of practicality is what one seeks. Whereas in folklores (lukh paech) the belief is stressed upon in written literature.

The existence of both marks the literary genius of Kashmiri culture, existing in the conversations familiar to the stem and root of the language.

Kashmiri folk literature is one of the richest, mostly pedagogical, partially reliable and a mark of the rich literary heritage. Other forms of Kashmiri folk literature like opera (Lukhi shiear), oral stories (Lukhi peathir), proverbs (lukhi Daleel), riddles (praitichi) and children’s literature (shuer ade’b) have helped in shaping the essence of Kashmiri community.

The shift to reality from supernatural characters are personage to the cultural and ethnic morale of the group. The power of these stories is such that it transports us to where we resonate- the landscapes, the tapestry of times, the lakes that are relevant in stories and the reality preserves our cultural wisdom.

Kashmiri literature has inherited all these forms of folklore including some extra forms like – Ladishah, Wanwun, Rouv, Dastaan, Bhand Paethir, Watchun that are unexplored and unsung.

These tales are woven around the ordinary and superficial social imbalances, economic exploitation, religious exploitation, government negligence, social issues, historical events and work on exposing all calamities that go unheard and unnoticed when these stories, symbols and rituals construct the subjective truth (myths) of ancient and modern establishments.

Kathāsaritsāgara (Ocean of streams of stories) was written 900 years ago, in the 11th century by Somadeva. The book was adapted, written and assembled in Kashmiri from the poorly understood and not extant language- Paiśācī.

Rev. John Hinton Knowles translated and wrote the first collection of folktales and folklores from Kashmir towards the end of the 18th century. He authored two books – A Dictionary of Kashmiri Proverbs and Sayings in 1888 and Folk Tales of Kashmir in 1893. Renowned scholar, Sir Auriel Stein also published a collection of folktales of its kind. The latter called it Hatim’s tales, which was a collection of tales in verse and prose recited in Kashmiri. He named his work after a Kashmiri, who was an oilman by profession.

Creatures local ‘Kashmiris’ believe in :

The following are the gabbed and less believed creatures and tales that are locally famous and often brings a tête-à-tête in Kashmir

A Rantas is a feminine character that calls you by your name and if not answered, she may call again and again. The third and final time she calls you, she stammers. Different regions from Kashmir have various versions of Rantas. Some believe that the Rantas may call you out and pretend to be your maternal aunt. Others believe in the fact that she has inverted feet and long hair that she incessantly combs and rejoices in scaring men.

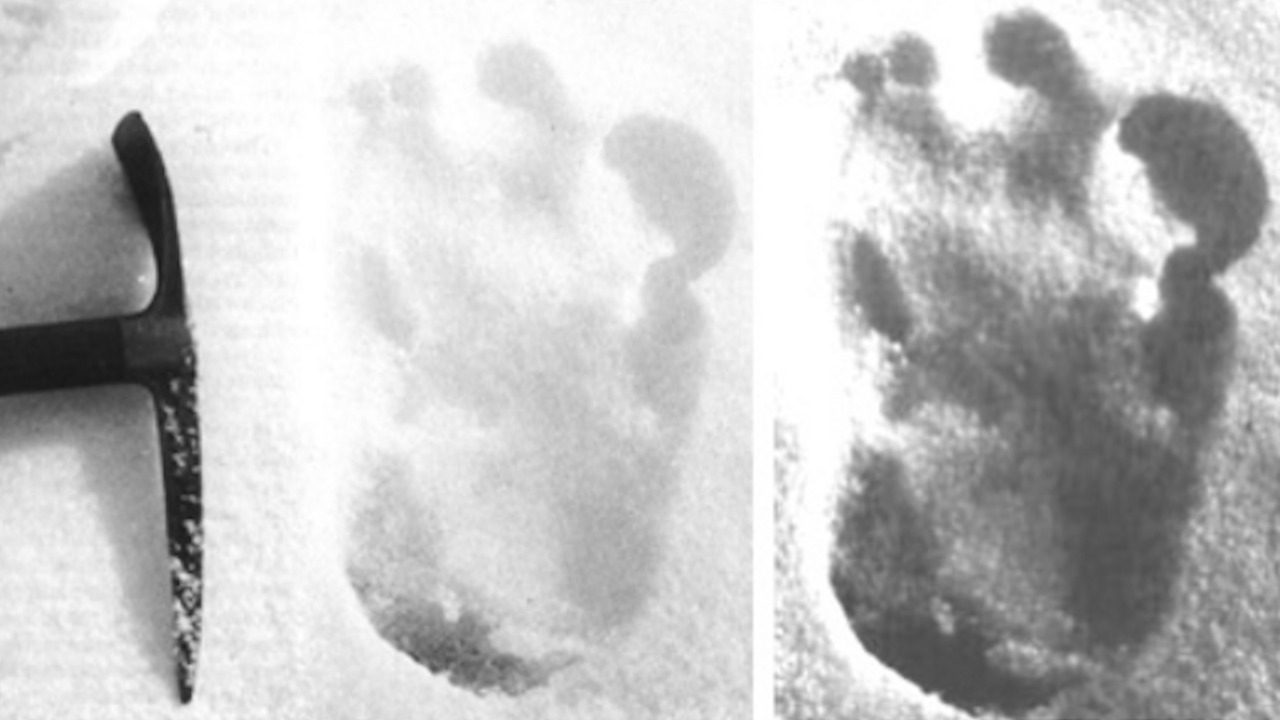

Wanmohniv is a mythological male character that lives in far off jungles, described somewhat between humans and monkeys, it is most commonly called a ‘Yeti’ or ‘Big Foot’.

Bramrakh Kuj or Bram Bram resides by streams and water bodies. Apparently, locals believe that this entity pushes you in the lake or the water body that you are standing close to. Some believe that Bramrakh Kuj has a glowing antenna on his head while the other variation of the myth states that he holds a lantern and waits in the dark for you to be pushed.

Gorkha digs out freshly buried corpse if buried late, after sun sets. Locals sprinkle graves with garlic water to avoid a visit from Gorkha.

Yach is believed to be found in and around bathrooms and unclean spaces. He would yell ‘be aawus, be aawus’ (I’ve come). He wears a magical cap, and locals believe that if you snatch it, he will solicit and beg you for it. Apparently, one can then manipulate Yach and ask him to carry waters in a porous container, after which he gets frustrated and asks you for wishes- Works like Aladin ka chirag.

Gud balai is another mythological animal, that was feared largely amongst the nomads who had herds of sheep and goats. It is said, that Gud balai hunts down other domesticated animals and leaves behind the horns or the carcass.

Maagmaas is an entity that usually dwells in the dark and only shows up during winters. It is said that if you strode out late with a Kangrhi – Maagmaas will snatch the Kangrhi and throw it your way.

Another variation of a ‘Rantas’ is ‘Wai Wouph’. Central Kashmir, North Kashmir and South Kashmir have variations in these stories and the said creatures.

Inflicting terror with braid choppers and ‘Daens’:

After the uprising of 2016 in Kashmir, came a brief period where Kashmiris lived in fear and hysteria because of braid choppers. The first few incidents of the unexplained events began in September of 2017, after which the schools were shut for a long time as the situation became volatile in Kashmir valley.

According to testimonies, women would fall into a trance-like state after being attacked from behind and fall to the ground unconscious, only to wake up in distress and inches of their hair chopped.

More than 40 incidents were reported in different parts of Kashmir, that reeled in vigilantism, violence, the blame game (where separatists blamed the government and vice versa). Young boys from the valley would take turns in the night and guard their localities. A young man was beaten to pulp as he was ‘suspected’ and mistaken as a braid chopper.

While elders blamed a supernatural being and the corrupt or immoral state of the residents for the hysteria, the more politically charged and well-read population, termed it as a tactic to infuse fear among Kashmiris.

A local resident of Rainawari, Fahd, remembers an incident that rattled downtown in Central Kashmir’s Srinagar. Locals, in 1993 feared a supernatural entity or ‘Daen’ that would come to their houses at wee hours and pick up young boys from the heart of ‘Shehr – E – Khaas‘.

Locals began questioning the fate of the entity and its legitimacy when Rasheed, a local butcher, followed this ‘Daen’ that had entered his house and tried snatching his teenage boy.

He ran after the silhouette draped in black and threw one of his knives at it. He saw blood oozing from the draped silhouette’s leg and as the black drape moved, camouflage print stained red from the wound flashed before his eyes. He watched the silhouette run for its life and jump in the back of a car. The car rushed as Rasheed followed it. After Rasheed’s rendezvous with the ‘Daen’, the locals lived less in fear, while Rasheed lived with the truth.

The nature of oppressive and at times atrocious conservative structures of differing political motives is to identify our weaknesses, our fears, and cripple us within them.

Reason can be a privilege, that only few can afford at times, and it directs the demon, only forcing us to believe that the mysterious and undiscovered truth can be the safe haven to their woven psychosis. Thus, the ancient wisdom that stresses upon triumph over evil, lures our emotional and fragile state of mind into believing the narrative, for the benefit of the one that wants to infuse the state of fear, hysteria and psychosis in the present day.

The current turmoil in Kashmir has changed the dynamics of panic and neurosis. The entities and tales that once infused fear and terror are now replaced by trauma and trajectory by violations of rights and inhumane actions. Beyond structures of religion and the demands of honor exist windless, dismissive, drear, and obscure hollows, where the power of purpose meets the weight of allegories and imponderabilia.

A similar incident that follows is of a village in Banihal, Bohrgam, where Nazreena Prehnu was followed by a ‘Rantas’ when she was on her way back home after spending the day picking up and chopping wood in the forest that their family would burn to stay warm for the winters.

Nazreena walked downhill with the bundle of sticks as she heard a mellow, feminine voice call her name. According to Nazreena, the voice did not comfort her, it only made her anxious and thus she ran. She heard footsteps following her, as she turned to this voice calling her name, she saw a tall, beautiful woman with inverted feet that did not look human.

Nazreena fell into a trance-like state and woke up hours after the incident. She rushed back home and lives to tell the tale.

While people in metropolitan cities will choose not to believe in what the traditional beliefs are. The ones who have witnessed live bearing the only proof they can afford, which is credibility and blind belief.

The new year of 2021 brought in the gospel gossip, that a similar ‘bala’ was found roaming out and about the streets of Anantnag in Kashmir.

Users on Twitter did not take long to come up with memes and pictures of inverted feet, while local news channels streamed a fabricated video of a voice calling out the names – ‘Junaid’ and ‘Sehrish’, that went viral on the social media.

Officials released a statement asserting that anyone who indulges in spreading fake news and hysteria among people will be charged and arrested.

The Kashmiriyat spoke to Onaiza Drabu, a Kashmiri anthropologist. She writes about identity, nationalism and Islamophobia, and co-curates a newsletter called ‘Daak’ on South Asian literature and art.

Onaiza wrote her first book ‘The Legend of Hirmal and Nagrai’ – which is a compilation of folk stories and tales from Kashmir. On preserving culture and stories with literature, Onaiza said, “Oral folktales and folklore is a genre of its own, because it gives the sense of rooting, and mostly takes us back to what our history is. It takes us back to the origins of stories and superstitions. We have a lot of stories and tales that talk of ‘Naags’ (Springs). We have these because back in the day, bodies of water were also the ways of sustenance, a lot of mythologies revolve around them. Folktales provide a broad platform to get to know who we are”.

“In times like today when everyone is talking of global content, the nuances of cultures are being lost. No matter how problematic, patriarchal and orthodox these stories might be in nature, they are also a source of the ecosystem of cultures. There is also this bit about languages, it is another thing to read these stories in English, but the true authenticity exists in Kashmiri. It is a way of getting back to their language,” she told The Kashmiriyat.

In times like these, it becomes difficult for people to draw a fine line between aphorisms, myths, hysteria and belief and when asked about, Onaiza said, “There is a difference between hysteria and stories and the scare in Kashmir, where a terrible fabricated audio recording circulated amongst the people was absurd. People went vile with audio and superstition draws a fine line between being scared and faith”.

Rantas, Agarpeczin and Yach are all tales that hold us close to our language and community. On language and diaspora grounding the roots of culture, Onaiza concluded, “The familiarity of language and reading the tales conjure up so many stories that are in your subconscious and bring you home. It is like a way of connecting to home, away from home. It transports you back to your childhood. Preserving these stories becomes important as generation after generation, the translations and essence lose value”.

Active efforts of preserving these tales and stories are made by Kashmiris. Ghulam Nabi Atish, Professor Fayaz Farooq, M.K Raina and many others, contribute to the cause, in their own ways.

On M.K Raina’s official website, there is a section called Grandma’s tales, that talks about traditional stories that were passed on from generations and beyond that take you back to your childhood.

Like Neil Gaiman wrote in The Ocean at the End of the Lane – “I liked myths. They weren’t adult stories and they weren’t children’s stories. They were better than that. They just were.”