In a significant development in the case challenging the Waqf Amendment Bill, the Supreme Court on Tuesday made key interim observations aimed at preserving the status quo on waqf properties and administrative provisions while the case is under consideration. However, the Court clarified that no formal order has been passed yet, and arguments will continue on Thursday.

Chief Justice of India (CJI), who is heading the bench, acknowledged that while courts generally refrain from issuing orders at the admission stage of a case, the potential consequences in this matter demanded immediate attention. “Normally, when a law is passed, courts do not issue orders at the stage of admission. However, in this case, we believe that if a waqf property—especially one established by long-standing usage—is denotified, there could be grave ramifications,” the CJI said.

The Court emphasized that properties already declared as waqf—whether by a court or through usage—should not be denotified or treated as non-waqf in the interim. Although the Collector may continue with ongoing proceedings, the specific provision under challenge will not be enforced at this stage.

In relation to the composition of Waqf Boards and Councils, the Court stated that ex-officio members can be appointed regardless of faith. However, all other members must be of the Muslim faith. The CJI also noted that existing boards have a defined tenure, which must be honored.

Solicitor General Tushar Mehta, appearing for the government, requested the Court to record a clarification. “Please record my statement that a maximum of two non-Muslim members will be appointed,” he said.

Despite the detailed observations, the bench concluded the session without passing any interim order. The matter is now scheduled to be heard again on Thursday.

Mehta had earlier defended the government’s position, arguing that waqf properties must comply with registration mandates dating back to 1923. According to him, the legal framework—reaffirmed in 1995—requires formal registration, even for waqfs established through longstanding community use. “Even waqf by user cannot be unregistered,” he told the court, adding, “Mr. Sibal says the Mutawalli will go to jail — he’s been going to jail since 1995 for failing to register.”

However, the bench expressed strong reservations about such a rigid interpretation. Chief Justice Khanna emphasized that waqf by user had long been recognized, particularly for sites that predate modern laws. “Let us be clear—waqf by user has been accepted before 1925. If it’s already established, will it now be declared void? Be careful with your statement,” the CJI warned. He cited iconic structures like Jama Masjid Delhi, questioning the logic of asking centuries-old religious sites to now furnish sale deeds or registration records.

The CJI further highlighted the impracticality of applying modern registration requirements retroactively. “Masjids were built in centuries ago. You are now requiring them to produce a sale deed? That’s impossible,” he said, pressing Mehta to consider the historical realities of such properties.

Justice Viswanathan also raised concerns around Section 3(C) of the Act, which allows the government to assert ownership of properties considered waqf by communities. He referenced the Land Encroachment Act, noting that the courts are supposed to assess bona fide title in such cases, rather than administrative authorities. The CJI echoed this view, asserting that the question of whether a property remains waqf should be decided by a civil court, not by collectors or executive officials. “Why will it not remain a waqf property? Let the civil court decide that,” he remarked.

Mehta countered that the government’s role stems from its duty as a trustee of public interest. “There are judgments which state that if there’s a question over whether a property is government-owned, the Collector has the power to determine it,” he said. He also compared the structure of waqf administration to Hindu endowments, noting that while the latter are generally community-based, Islamic law requires a waqif—a person dedicating the property for religious purposes—and a Mutawalli for its management.

The CJI was not entirely convinced by this analogy and emphasized the need for parity in how religious endowments across communities are treated. The bench repeatedly pressed Mehta to explain how the law accounts for religious diversity while safeguarding constitutional rights.

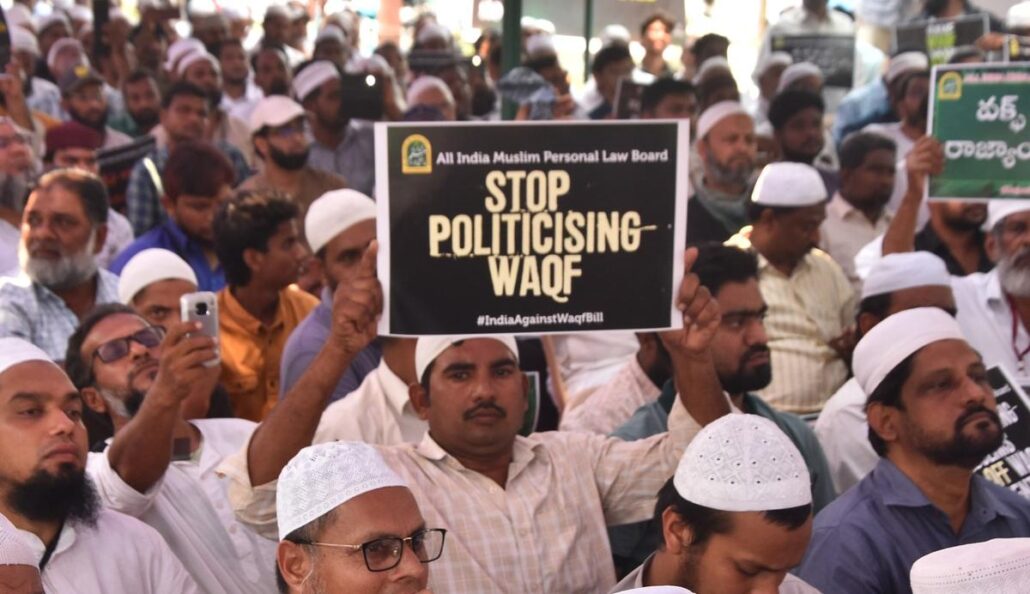

Meanwhile, petitioners challenging the Act argued that the amendments represent an assault on religious autonomy. They alleged that the inclusion of non-Muslim members in Waqf Boards and the Central Waqf Council violates Articles 14, 15, 25, and 26 of the Constitution. These provisions guarantee equality, non-discrimination, and the freedom to manage religious affairs. Petitioners also objected to the removal of the waqf by user doctrine, which they said is essential for protecting properties that have served religious functions for centuries but lack formal documentation.

They also criticized new restrictions, such as requiring individuals to prove they have practiced Islam for five years before creating a waqf. In their view, these conditions are inconsistent with Islamic principles and introduce arbitrary barriers to religious endowment.

Petitioners further raised concerns about the centralization of control, particularly provisions granting district collectors authority over waqf property disputes—powers previously exercised by Waqf Boards. They warned this could open the door to political interference and potential misuse.

The petitioners urged the Court to stay the implementation of the Amendment Act, warning that without intervention, there would be “immense and irreparable loss” to historical waqf properties and Muslim religious rights.

Live Updates

CJI asks: “will allow Muslims to be part of the Hindu endowment boards.”

CJI comments: “If a public trust was established 100 or 200 years ago and has functioned as such ever since, it cannot suddenly be reclassified as a waqf and taken over by the Waqf Board. History cannot be rewritten.”

CJI: “Ordinarily, when a law is enacted, courts do not pass orders at the admission stage. However, in this case, we believe that if a property classified as waqf by usage is denotified, it could lead to grave ramifications. As for the waqf boards that are already in existence, they have a fixed tenure which must be considered.”

SG Mehta stated: “Please record my statement that a maximum of two non-Muslim members will be appointed.”

Supreme Court proposes order in petitions challenging the Waqf Amendment Act 2025

The Supreme Court has proposed the following order in response to petitions challenging the Waqf Amendment Act 2025:

-

Protection of Waqf Properties: The Court intends to direct that properties declared as Waqf by the Courts—whether through waqf by deed or waqf by user—shall not be de-notified during the ongoing challenge to the Waqf Amendment Act 2025.

-

Proviso on Waqf Properties and Government Land Inquiry: The Court further proposes that the proviso in the Amendment Act, which allows a Waqf property to be treated as non-Waqf while the Collector conducts an inquiry to determine whether it is government land, will not be enforced.

-

Composition of Waqf Boards and Central Waqf Council: The Court has also stated that all members of the Waqf Boards and the Central Waqf Council must be Muslims, with the exception of ex-officio members.

-

CJI: No order is issued, the matter shall be heard tomorow.