Fizala Khan

Prominent Kashmiri author, Ather Zia has been awarded ‘Honor Our Heroes 2021’ as ‘Kashmir advocate of the year’ Award, for her work on Kashmir by Justice for all (JFL), which is an NGO with consultative status at the United Nations (DPI), as a non – profit organization in Chicago.

Ather Zia has previously been granted the Public Anthropologist Award for her extraordinary commitment that follows the themes of savagery, war, destitution, social developments, opportunity, help, rights, treachery, imbalance, social prohibition, prejudice, and conflict, both political and personal. Her examination investigates militarization, pioneer imperialism, and women of aggregate political and social difficulties in Kashmir.

Zia is also, is the founder and editor of Kashmir Lit (a literary magazine) and is the co-founder of Critical Kashmir Studies Collective, an interdisciplinary network of scholars working on Kashmir.

She has been featured in the Femilist 2021, a list of 100 women from the Global South working on critical issues.

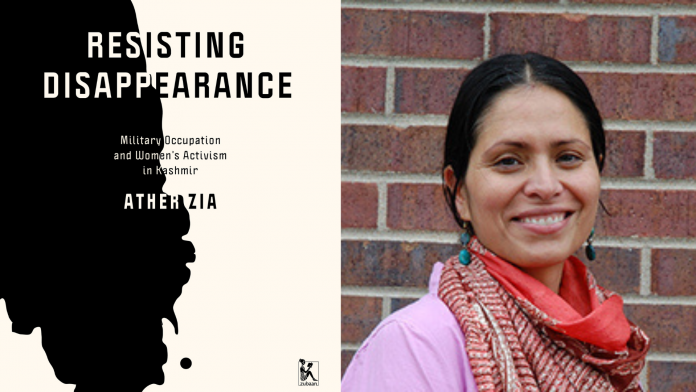

Zia is the author of Resisting Disappearances: Military Occupation and Women’s Activism in Kashmir (June 2019) which won the 2020 Gloria Anzaldua Honorable Mention award, 2021 Public Anthropologist Award and Advocate of the Year Award 2021.

She is the co-editor of Can You Hear Kashmiri Women Speak (Women Unlimited 2020), and A Desolation called Peace (Harper Collins, May 2019).

Zia has also published a poetry collection “The Frame” (1999) and another collection titled “In Kashmir” (Red River Press) is forthcoming. In 2013 Ather’s ethnographic poetry on Kashmir won an award from the Society for Humanistic Anthropology.

Her book subtleties the impacts of military control and political question of two nations India and Pakistan on regular daily existence of a Kashmiri and the book centers around the situation of Kashmir from the previous years which incorporates implemented vanishings and recounts the account of Kashmir through women and their activism in the battle.

Resisting Disappearance is the portrayal of mistreatment and political debates on the existence of Kashmiri individuals and the recurring impact of the regime. It successfully sums up the wide and submitted grant behind it. An incredible illustration of human sciences’ ability to both educate and rouse.

Zia has a doctorate from the Department of Anthropology at the University of California at Irvine. She likewise has two master’s Degrees: one in Communications from California State University Fullerton and another in Journalism from Kashmir University.

Currently, she is an Associate Professor in the Anthropology Department and Gender Studies Program at the University of Northern Colorado Greeley.

She has been a writer with BBC World Service and has likewise done a short spell as a government employee with the Kashmir government which is a lighter vein she alludes to as her pre-fundamental fieldwork. She is a distributed creator and writer. Her articles and innovative work including fiction and verse have shown up in an assortment of magazines.

In 2013 she won the second prize for an ethnographic verse on Kashmir from the Society for Humanistic Anthropology (American Anthropological Association).

Zia was chosen for the leading body of Society of Humanistic Anthropology (SHA) of the Anthropological Association of America (2015-2016) and was the book survey proofreader “choose” (2017), for the Anthropology News (Association for Feminist Anthropology Section).

Her ethnography depends on her doctoral examination on authorized vanishings, militarization, sex, and denials of basic liberties in the Indian-controlled Kashmir. Among other presumed organizations the Wenner Gren establishment, American Association of University Women, International Peace Research Association Foundation, and Human Rights Centre of Berkeley have upheld her examination with insightful undertakings of gathering unequivocally centers around applied and connected humane research.

The following poem is from the collection of yet-to-be-published compilation that first appeared in scroll on life – and death – in the valley.

In Kashmir: Writing under Occupation- By Ather Zia

They want us to write in blood and only write of peace. They capture our land. make us sow rice that is not seeded. Kill us. rape. They tell us we are ungrateful, like children – who do not see what is good for them. Holding us with many kinds of guns; they grimace at the world calling our blood on their faces –vermillion.

They sell pens. We buy with blood.

Many of them, from their mythical land come to us, with clean hands, softened in the Ganges. They meet our eyes. That gaze, which through you goes elsewhere. Behind their orange irises you see wheels turning. like the innards of a swiss – watch. Precise. Surgical.

They sell paper, so much paper. We buy with blood. They put the kettle on boil. It whistles. The seduction of tea. There is no better heaven. Our pens poised. The next word will liberate. An orgasmic lull prevails. That next sentence, always in arrival, like that justice thing. Meanwhile Ashfaq is no more. Maqbool has gone. Asiya and Neelofar, raped then killed. Afzal hanged. Tufail, buried in two graves. The Ittar seller in Lal chowk disappeared, they found his bones with empty – bottles, the kettle whistles.

The tea never comes.

Our bones are made tired. Waiting. Before the door of law from that overused Kafka tale. The only thing that grows after this wait, are their swords. Looming mightier, and this too, we write.

“The myth of the ‘backward’ Kashmiri woman is perhaps the biggest lie”

The Kashmiriyat, in an interview with Ather Zia, questioned her about the social media censorship and the accounts of Kashmiris being suspended as a rigorous tool to satisfy the collective of the authoritarian state. Zia said, “It is a tool of repression and in the case of Kashmir one of the modes of repression and to subjugate Kashmiri resistance and voices. The level of surveillance on what is communicated by Kashmiri writers, activists, and average regular social media users to the outside world is currently at an all-time high. The government of India often alleges violating India’s Information Technology Act which allows them to censor online content that is touted as posing a threat to the sovereignty of India. As we know that by their sheer existence Kashmiris pose a threat to India and as such terror charges are routinely invoked against them – even for breathing it seems. Kashmiri social media users are often banned, and many have been incarcerated for writing simple posts”.

She further adds, “Now I hear that the government employees have to submit their social media accounts only then will their salaries be released. The message is that anyone who writes about Kashmir is under a strict panopticon gaze. Digital apartheid and strict – censorship, is a historical reality in Kashmir, but now it is fully institutionalized and legalized. As the Indian state gets more insecure it gets intense. The repression of explicit expression is everywhere. The government authorities enforce a silence, which manifests as blatant censorship or penalization of any resistance narrative, symbol, or event. The normal routines for how people commemorate and remember those killed or maimed or incarcerated by the Indian occupation have become impossible. The current Indian ruling government surpassing the past administrations in being openly Hindu supremacist and ethno-nationalist has choked the scribes, writers, and opinion leaders from voicing freely the ground realities of Kashmir”.

The Kashmiriyat also spoke to Zia about the authoritarian democracy playing with the narrative of Kashmir, and she said, “We cannot validate India’s deployment and weaponization of electoral democracy and symbols of democracy by calling it democracy of any form or type. That would be adding to the obfuscating Indian narrative about Kashmir. Call an occupation by its name and then everything falls in place”.

On the position of women, as patrons and representatives of Kashmir, she said, “The intersectionality of being women, Kashmiri, Muslim in a military control that is ethnonationalism and Hindu supremacist is not easy. On the other hand, the gender inequities and discriminations already present in our society are getting exacerbated. Even then Kashmiri women are staying the course, as they have done historically. Indian narrative often has presented Kashmiri women as victims – not only of war but also victimized by their male counterparts”.

She further added, “Women are often deployed as a tool to undermine Islam, Muslims, and dismantle the idea of resistance as well which is male-dominated. Kashmiri women are often patronized and seen as subjects that need rescuing from their men. Not to glorify the sufferings but Kashmiri women have been courageous in showing how to survive but also to thrive. Recently when after 5 August 2019 a few Indian activists visited Kashmir, they published a report and made an observation which is rare in the Indian narrative that never refrains from bolstering the stereotype of the victim Kashmiri woman”.

“They reported: “the myth of the “backward” Kashmiri woman is perhaps the biggest lie. Kashmiri girls enjoy a high level of education. They are articulate and assertive. Of course, they face and resist patriarchy and gender discrimination in their societies. But does BJP, whose Haryana CM and Muzaffarnagar MLA speak of “getting Kashmiri brides” as though Kashmiri women are property to be looted, have any right to preach feminism to Kashmir? Kashmiri girls and women told us, “We are capable of fighting our own battles. We don’t want our oppressors to claim to liberate us!” This mention proved that despite so much propaganda about Kashmiri women, the urgency of their agency could not be ignored. They have held communities together, nurtured resistance and overcome social rigors in the most creative ways. They deserve their personal and political freedom and fast”.

Ather Zia in coalition with Nitasha Kaul wrote for the Economic and Political Weekly under ‘Review of Women’s Studies. In Vol. 53, Issue No. 47, date – 01 December of 2018, she wrote about understanding women from the conflict zone in ‘Knowing in Our Own Ways – Women and Kashmir’.

When it comes to international conflicts, ignorance is as much an ally as ill-will in their prolongation. The vested interests entrenched in profiting from conflict, unsurprisingly seek to limit the range of possible political options that might lead to demilitarization, dialogue, conciliation, a just peace, and eventually resolution. However, the means by which the conflicts are prolonged relate just as much to the usually effective embargoes on what kind of knowledge can be produced about the conflict, by whom, and with what kind of visibility. This is acutely so in the case of Kashmir, where ignorance and ill-will work synchronously to produce a simplistic understanding of the region that belies its complexity in terms of its history, politics, competing claims, traumatic memories, divided populations, lack of justice, denial of rights, loss of homes, and cycles of extremism, corruption, and occupation. The mainstream understanding of Kashmir outside the region and globally is predominantly through the prism of an Indian and Pakistani statist narrative. There is little space for Kashmiris and their knowledge in their own ways; even less for Kashmiri women speaking about women and Kashmir.

The Kashmiri women herein speak of myriad things: of spectacles and street protests; women’s companionships and female alliances; women’s movements and imaginaries of resistance; the links between militarization, militarism, and the creation of impunity by the law; competing patriarchies and sexual violence as they seek to break Kashmiri communities; the infrastructures of control that limit their mobilities, bodies, and experiences; public grief at funerals as a challenge to Indian sovereignty over Kashmir; and autobiographies, oral histories, and the textures of political memories. In the powerful idiom of postcolonial criticality, the question we should ask is not “Can the Kashmiri women speak?” but rather “Can you hear them?”.