Bhat Yasir

Mir Sayyid Ali Hamadani’s (also known as Shah e Hamdan or Ameer e Kabir) journey to Kashmir was driven by his religious fervor, widely regarded as an Islamic mission by scholars. According to the author of Risala-Masturat, Hamadani’s visit was guided by a divine directive from Prophet Muhammad (Peace be upon him).

The socio-political and religious climate of Kashmir at that time seemed conducive to his missionary endeavors, suggesting a pressing need for a reformer, preacher, and thinker like Hamadani. Before his arrival, Kashmir had seen the rule of various Muslim leaders, yet societal issues such as caste discrimination, mistreatment of women, and religious confusion prevailed.

Though historical numbers differ, one of the most credible evidences suggests that under Shah e Hamdan, more than 37,000 people accepted Islam and one of the most challenging tasks for the Sufi preacher was to empower Kashmiris who had accepted Islam.

Mir Syed Mushtaq Hamadani Says, “When Amir-I-Kabir, Mir Saiyid Ali Hamadani came to Kashmir from Ladakh, he brought with him Pashm and after arriving to the valley, he got the processing of Pashm affected and started various varieties of Pashmina work conducted. He prepared a pair of socks with his own hands and gifted that to Sultan Qutub u Din”.

On his second travel to the valley, Shah e Hamdan was accompanied by 700 Sa’adaat, who were a team of esteemed scholars and artisans, including Khwaja Ishaq Khatlani and Shaikh Qawam-al-Din, among others. This diverse team not only contributed to religious scholarship but also brought economic prosperity to Kashmir through their skills and expertise.

Historians unanimously attest to the peaceful nature of Hamadani’s mission, devoid of coercion or forceful conversion tactics. Despite the prevailing moral decay and societal unrest, his approach garnered significant support, resulting in a notable number of conversions to Islam within a brief period.

In terms of religious practice, Hamadani adhered to the mainstream of Islamic thought, focusing on the principles of the Qur’an and Sunnah. While he belonged to the Sha’afi school of thought, he did not denounce other practices followed by Kashmiri Muslims, promoting a non-sectarian approach to his teachings.

His emphasis on the unity of believers and adherence to core Islamic principles resonated with his followers, as reflected in his writings such as the Awrad-i-Fathiya, where he states,

*رَضِيتُ بِاللَّهِ رَبًّا وَبِالإِسْلاَمِ دِينًا وَبِمُحَمَّدٍ نَبِيًّا*

“And the Qur’an is the guide, The Ka’abah is the Qibla (direction of prayer), and (five times) prayers are obligatory, and all believers are brethren.”

He was unlike most of the saints in the valley and perhaps that was the need of the time, which facilitated the preceding saints to adopt a saintly life. His rejection of idle Khanqah life fostered his connection with common people. His influence extended to poetess Lalla Ded, who rejected the caste system under his guidance.

Besides being an ‘Aalim and Sufi, Hamadani was an influential political thinker and a reformer of high repute. His impact on all sections of Kashmiri society was primarily due to the integrity of his personal life. He laid great emphasis upon earning one’s own livelihood and rejected the traditional means of patronage and support open to religious men such as Futuh (unasked for charity), Ihya (the cultivation of wasteland), or Madad-i-ma’ash (grants from the state).

His Khanqah in Srinagar was open to all from Sultan to a poor Hindu. He had no reservation in counseling monarchs because he saw that their policies were the key to the welfare of people. Shah e Hamdan’s introduction of the tradition of dhikr was motivated by his desire to bring different sections of Kashmiri society together.

The dhikr of Awrad-i-Fathiya, ceremonies after the Fajr (morning) prayers and Isha (night) prayers served the social purpose of gathering different people together twice a day, without reference to their wealth or poverty. Under the influence of Hamadani’s son, Mir Sayyid Muhammad Hamadani, Sultan Sikander banned all intoxicants, the custom of Sati, and other harmful social practices in Kashmir.

Mir Syed Ali Hamdani corresponded with Qutb-ud-Din who became his disciple and wrote several verses in his honor. The Sultan who had married two sisters in contravention of the Shari’ah went to the extent of divorcing one of them at the urging of Hamadani. Further, at the instance of Sayyid Hamadani, Sultan Shihab-ud-Din established the first Madrasat-ul-Qur’an. Schools were also established to teach the basics of Islam in important villages of Kashmir.

Sultan Sikander, who succeeded Qutb-ud-Din, was, as a result of Hamadan’s writings, more inclined towards religion than many of his predecessors. He attempted to introduce Shari’ah law in his Sultanate. Shah e Hamdan was, at the same time, careful about keeping a personal distance from the state to preserve his independence. When Sultan Qutb-ud-Din invited him to stay with him, he declined and stayed in a Sarai (resting place) until his Murids built him a Suffa (plinth) after which he began living there.

Shah e Hamdan’s Zakhirat-ul Muluk was a favorite book with the scholars during the pre-Mughal period in India. This is borne out by the fact that most of the orientalist libraries contain manuscript copies of Zakhirat-ul Muluk while this is not the case as far as Fatwa-i-Jehangiri or Fatwa-i-Firoz Shahi is concerned. One of Hamadani’s impacts of great significance was the emergence of a network of Khanqahs which served as great centers of proselytization especially at Hindu-rich Centers like Pampore, Awantipora, Bijbehara, Shahabad, and Tral. Allama Iqbal beautifully pays tributes to Hamadani and declares him chief of Sa’adaat and maker of the destiny of the Muslim Ummah.

The local response to Hamadani’s teachings came in the form of the emergence of an indigenous religious order, the Rishism, being its founder Shaikh Noor-ud-Din (R.A). Dr. Enayatuulah Indrabi visualizes the impact of Hamadani on Shaikh Noor-ud-Din in these words: “…The arrival of Amir-e Kabir is by all standards a turning point in the history of Kashmir. It heralded the dawn of the new era in the sense that the history of Kashmir took a decisively a new turn and a vigorous process of socio-cultural change got initiated when Hazrat Shaikh started his movement and made a frontal attack on the prevalent social ills, hypocritical practices and the Ulema who did not practice what they preached, the new society was yet in a nascent stage. The social reality that came under attack from Hadrat Shaikh could neither be defined nor described without a broader reference to the new historical phase that had set in with the arrival of Hazrat Amir e Kabir …”

In fact, the increased cultural contacts between Central Asia and Kashmir during the medieval period were largely a result of the missionary activities of Sufi saints from Persia and Central Asia like Sayyid Ali Hamadani, Bul-bul Shah, Mir Shams-ud-Din, and many others.

Shah e Hamadan made strenuous efforts to reform the social and political ethos of the community. For this, he wrote many letters, which are mentioned in Risale-i-Maktubat, to the rulers in which he gave them guidance on political matters. Then he wrote on the request of many rulers, nobles, and government officers Zakhirat ul Muluk.

Shah e Hamadan was quite aware of the benefits of trade, commerce, and other means of earning livelihood. So he introduced the pattern prevailing in Central Asia. He vehemently argued against monasticism, for he had observed closely the deteriorating condition of the church and monasteries in Christendom and the Brahmanical order in India, both spiritually and morally. Shah Hamadan explains that the administration of social justice and the pursuit of trade and commerce will raise the spiritual status of the people.

The economic measures taken by him left far-reaching results. He introduced various arts and crafts, in Kashmir, especially shawl making, cloth weaving, and carpet manufacturing. Shah e Hamdan thus paved the way for a veritable revolution in the field of industry and commerce in Kashmir.

In recent times, Shah-e-Hamdan has primarily been associated with religious pulpits, where he has occasionally faced ridicule from certain clerics who openly criticize him, despite his role in spreading Islam in the valley. In the subsequent section of this essay, I explore his transformative contributions to the arts of Kashmir. These contributions liberated Kashmiri Muslims for generations and garnered Kashmir international acclaim.

Mir Sayyid Ali Hamadani, played a transformative role in the revival and flourishing of the shawl industry in Kashmir. The English word “shawl” is derived from the Persian term “shal,” which encompasses a range of fine woolen fabrics. Shawls have a long history in Kashmir, serving as staple garments for both the elite and common people since ancient times. In the 11th century, shawl weaving was already a well-established cottage industry.

Historical references highlight the significance of shawls in ancient Buddhist literature and their use among the elites of the Roman Empire. Despite this rich history, the shawl industry in Kashmir had faced periods of decline until its significant revival under Mir Sayyid Ali Hamadani in the late 14th century.

He reintroduced the craft to Kashmir by bringing advanced weaving techniques and skilled artisans from Persia and Central Asia. He introduced the kani weaving method, where intricate patterns were woven using small wooden bobbins. This technique allowed for the creation of shawls with elaborate designs that were both durable and aesthetically pleasing. Under Hamadani’s influence, Kashmiri shawls became renowned for their intricate craftsmanship and the use of fine wool known as “pashm.”

The revitalization of the shawl industry brought significant economic benefits to Kashmir. It provided employment to a large number of artisans and became a major economic driver for the region. The production and export of shawls brought wealth and recognition, establishing Kashmir as a leading center for luxury textiles. Kashmiri shawls gained popularity in European markets, particularly in London and France, where they were considered luxury items. Their demand was so high that the London Custom House imposed a high import duty on them, underscoring their value and desirability.

Shah e Hamdan’s contributions went beyond economic revitalization; they also had a profound cultural impact. Kashmiri shawls became a symbol of the region’s rich cultural heritage and skilled craftsmanship. The intricate designs and high-quality materials used in their production reflected centuries-old traditions deeply rooted in Kashmiri and Persian culture. The shawl industry flourished under Hamadani’s patronage, introducing new designs and patterns that became synonymous with Kashmiri shawls.

The legacy of his contributions to the shawl industry continues to this day. Kashmiri shawls remain highly prized for their beauty, craftsmanship, and durability. The techniques and designs introduced during his time continue to influence contemporary shawl making, preserving and promoting the cultural heritage of Kashmir. Hamadani’s efforts laid the foundation for a craft that continues to be celebrated and cherished worldwide, showcasing the enduring impact of cultural exchange and artistic innovation in local traditions.

Second only to Kashmir shawls in beauty, Kashmir embroidery represents a highly artistic yet decentralized craft in the region. Various intricate patterns such as shawls, Chinar-leaf, iris, dragon, and Ihassa became popular under this art form, gradually replacing older designs.

Embroidery in Kashmir received a significant boost with the arrival of Mir Saiyid Ali Hamadani, marking a new era of development.

The craft was executed in four distinct styles: Amli, Chiken, Doori, and Yarma. Products included bed covers, cushions, curtains, scarves, tablecloths, napkins, felt rugs, and of course, shawls. Beyond these traditional uses, embroidered articles like drapes, tea cloths, counterpanes, ties, dress pieces, and café cloths were also crafted and traded.

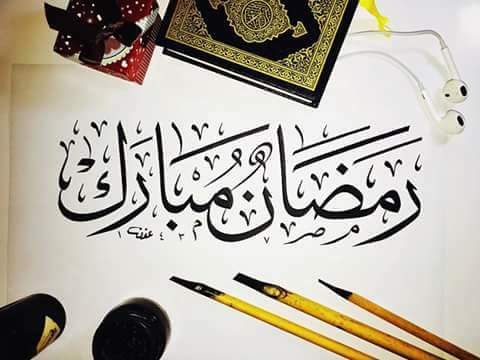

The art of calligraphy was introduced in the valley by Shah e Hamdan and then it got its stronghold at various places in Kashmir. Calligraphy is the art of decorative writing. Arabic alphabets in its various forms are used for writing both Arabic and Persian languages, which is so well adapted for decorative purposes that almost every Muslim building of importance is freely adorned with texts from the Quran or other inscriptions arranged decoratively to form part of the architectural design and often signed as the work of a calligrapher.

Shah e Hamdan, recognized as an expert calligrapher, played a pivotal role in promoting the art of calligraphy in Kashmir. According to Abul Fazl, during the late sixteenth century in Persia, Turkistan, India, and Turkey, various calligraphical systems were in use. These systems included diverse styles such as the Sul, Naksh (comprising one-third curved lines and two-thirds straight lines), Tauqi, Riqa (both incorporating three-fourth lines), Muhaqqaq, Raihan (each characterized by curved lines with one-fourth curvature), Tauliq, Riqa (featuring minimal straight lines), and Nastiliq (completely composed of curved lines).

The Sul, the Tauqi, and the Muhaqqah were characterized by thick heavy letters obtained with a pen full of ink, and conversely, the Naksh, the Riqa, and the Raihan by thin letters. The Nastiliq or the round Persian character was one of the favored both by Akber and Jahangir and consequently was specially practiced by Mughal writers from about 1560 A.D. to the end of the 17th century.

Professor Hamid Naseem Rafiabadi in his book Sufism and Islam in Kashmir writes, “The art of calligraphy was introduced in the valley by Mir Saiyid Ali Hamadani and then it got its stronghold at various places. It was unto the period of Zainul Abidin that about two dozen beautiful and captivating calligraphical designs including Khat-i-Dewani, Khat-i-Rugh, Khay-i-Reehan, Khat-i-Saroo, Khat-i-Shafeeah, Khat-i-Tugra, Khat-i-Ghubar, Khat-i-Kufi, Khat-i-Gulzar, Khat-i-Maghrabi, Khat-i-Makki, Khat-i-Madani, Khat-i-Muhaqqiq, Khat-i-Mahi, Khat-i-Munhani, Khat-i-Nakhun, Khat-i-Naksh, Khat-i-Nastiliq, and Khat-i-Shakastah were developed. Though later on, from all these calligraphical forms only three forms of calligraphy remained in vogue i.e., Khat-i-Shakasta, Khat-i-Naksh, and Khat-i-Nastiliq. These forms are still in use. In these calligraphical forms important and rare manuscripts, royal commands, classical poetical compositions, Reshinamahs, epic literature, important documents, religious and historical writings are preserved in various academic and literary centers and research libraries etc. It can’t be claimed that in making all these art forms prevalent in the valley, only Saiyid Ali was responsible single-handedly. However, this art form owes its origin to him to a great extent as he initiated the process of assimilation of Persian culture and its various manifestations in valley calligraphically included.”

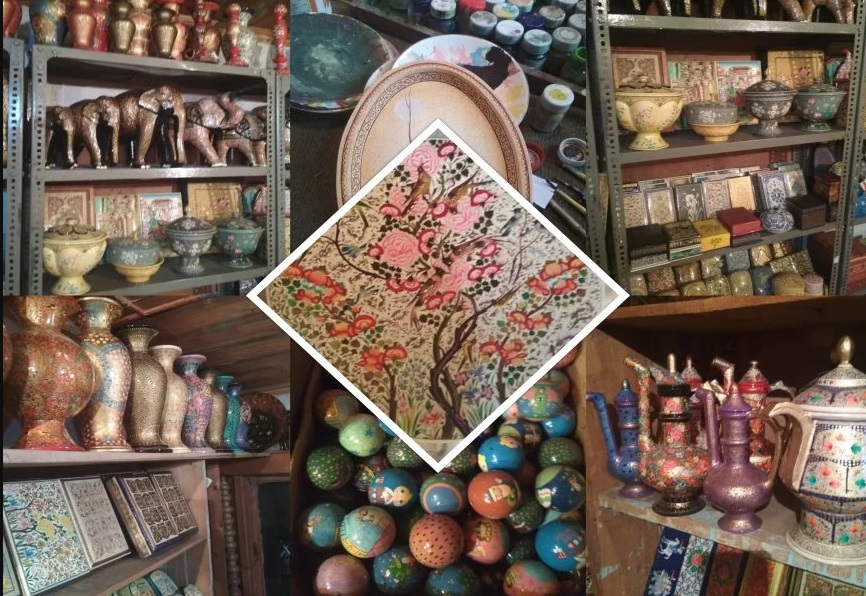

Papier-mâché, locally known as “Kar-I-Qalamdani” or pen-case work, is an art form deeply intertwined with Kashmiri culture, largely introduced and popularized by Mir Saiyid Ali Hamadani, also known as Shah-e-Hamadan. Alongside his religious teachings, Shah-e-Hamadan and his companions from Central Asia brought with them a rich cultural heritage that included expertise in various crafts, including papier-mâché.

Nishat Ansari acknowledges Shah-e-Hamadan’s significant cultural influence, noting that he and his group of preachers were well-versed in arts and professions, including papier-mâché. Ansari mentions in “Zakhirat-Al-Muluk” that Shah-e-Hamadan not only propagated religious teachings but also fostered cultural exchanges that introduced new arts and techniques to Kashmir.

The process of creating papier-mâché involves several intricate steps that were refined and perfected over time under the patronage and encouragement of Shah-e-Hamadan and subsequent rulers in Kashmir. Initially, layers of Kashmiri handmade paper were meticulously pasted onto molds of desired articles, forming a base for the craft. This base was then coated with a mixture of pounded Kashmiri scrap and rice paste, with additional layers of paper applied and allowed to dry, ensuring durability and strength.

Shah-e-Hamadan’s influence extended beyond mere introduction; he played a crucial role in establishing papier-mâché as a significant art form in Kashmir. His encouragement led to the development of new techniques and designs, particularly in applying intricate floral motifs and patterns that became characteristic of Kashmiri papier-mâché.

During the late 19th century, the demand for Kashmiri papier-mâché surged, driven by tourists and traders from cities like Calcutta and Bombay. Artisans responded by expanding their repertoire to include a variety of items such as tables, trays, screens, and decorative objects, all adorned with the distinctive floral patterns and designs inspired by Shah-e-Hamadan’s cultural legacy.

In summary, Shah-e-Hamadan’s contribution to papier-mâché in Kashmir goes beyond mere introduction; his patronage and encouragement nurtured this craft into a significant cultural and economic asset for the region, showcasing Kashmir’s rich artistic heritage to the world.

Mir Saiyid Ali Hamadani’s influence on woodwork in Kashmir was profound, revitalizing an ancient industry that had significant historical roots in the region. Before the advent of Islam in Kashmir, woodwork was already established as a prominent profession. However, it was under the patronage and encouragement of Mir Saiyid Ali Hamadani that this industry flourished and evolved significantly.

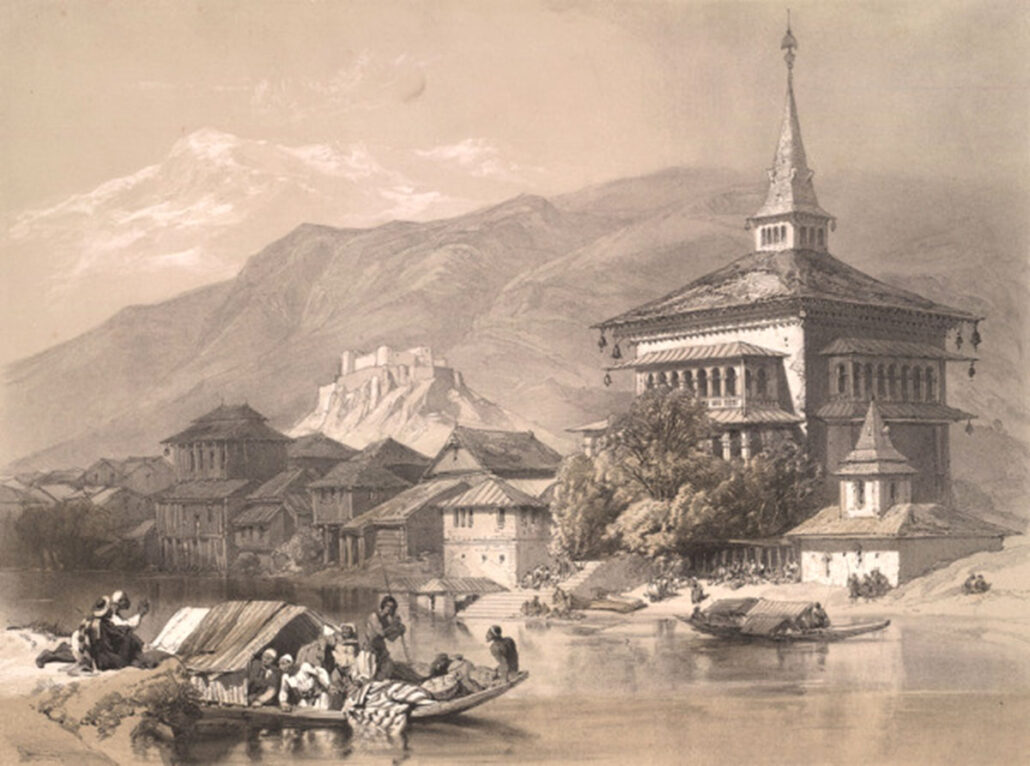

One notable aspect of Mir Saiyid Ali Hamadani’s contribution to Kashmiri woodwork is evident in the architectural marvels such as the Shah-Hamadan Mosque (Khanqah-i-Moulla). Unlike ancient Hindu buildings constructed primarily of stone, mosques like the Shah-Hamadan Mosque showcased intricate woodwork, highlighting the great skill and dexterity of Kashmiri carpenters under his patronage.

Initially, Kashmiri woodwork featured delicately carved surfaces with shawls, floral motifs, and geometrical patterns. Over time, however, the craft evolved towards more elaborate designs, including intricate border carvings featuring floral elements and dragon designs. Some designs were also borrowed from foreign catalogs, reflecting a fusion of local craftsmanship with external influences.

The availability of high-quality wood from Kashmir’s abundant forests played a crucial role in enhancing the skills of Kashmiri carpenters. They mastered techniques such as lattice work (Piinjra work), paneling (Khatamband), wood carving, and furniture making. Conifer wood, known for its durability and suitability for intricate designs, was commonly used for lattice work, which often featured bold and effective geometric or floral patterns.

Despite some critiques about the finish of Kashmiri woodwork by observers like Lawrence, who noted roughness due to challenges in obtaining seasoned walnut wood, the skill of Kashmiri carvers as designers was highly esteemed. They employed traditional tools such as hammers and chisels to create masterpieces that showcased their craftsmanship and artistic flair.

Mir Saiyid Ali Hamadani’s patronage significantly elevated Kashmiri woodwork to new heights, fostering innovation in design and technique that left a lasting legacy in the region’s cultural heritage. His encouragement not only revitalized the industry but also integrated diverse artistic influences, enriching Kashmir’s woodwork tradition with a blend of local craftsmanship and external inspirations.

Upon Mir Saiyid Ali Hamadani’s arrival in Kashmir, approximately 12,000 idol makers faced unemployment due to Islamic prohibitions against idol carving. Recognizing this challenge, Mir Saiyid Ali Hamadani encouraged them to pivot towards stone carving and other handicrafts, thereby providing them with alternative livelihoods. This pivotal shift not only sustained their economic well-being but also revitalized the artistic tradition of stone work in Kashmir.

Stone work in Kashmir encompassed two primary types: architectural and ornamental. The ancient heritage of architectural stone carving was exemplified by the majestic ruins of Martand, and it thrived under Mughal patronage, evident in the elaborate carvings adorning the pavilions and waterfalls of renowned gardens like Shalimar, Nishat, Cheshma Shahi, and Achabal. Over time, however, architectural stone work gradually receded into the background, giving way to the resurgence of ornamental stone work, which became a distinctive art form synonymous with Kashmir.

Ornamental stone work flourished anew with the crafting of various ornaments from imported precious stones, notably sourced from places like Samarqand. These stones were fashioned into buttons, beads, brooches, and other intricate designs, incorporating locally procured stones such as Takht-I-Suliman (black and white streaks), Sang-I-Musa (black crystals), and Sang-I-Sumak (blue or purple with green spots), among others found in different regions of Kashmir. Turquoise from Ladakh, prized for its charm, also played a significant role in this art, contributing to a vibrant trade.

Local lapidaries in Srinagar demonstrated remarkable skill in engraving Tograi monograms and producing items like cups and plates from stones such as Sang-I-Nalshan (soap-stone). Despite their proficiency, the lapidaries faced economic challenges; while the production of imitation jewelry became a lucrative pursuit under European and Indian influences, Lawrence noted that lapidaries did not enjoy substantial prosperity in Kashmir. Nevertheless, their craftsmanship continued to be esteemed, highlighting the enduring legacy of stone work in the region.

The carpet industry in Kashmir, renowned for its mastery and esteemed products in Europe and America, owes much of its development to the influence of Mir Saiyid Ali Hamadani. Historically, carpet weaving, known as Qaleen-Bafi in Iran, was already a well-established art form. When Mir Saiyid Ali Hamadani arrived in Kashmir, he introduced and encouraged the locals to adopt this art form. To achieve mastery, Kashmiri weavers traveled to Central Asia and Iran for training under expert artisans, which eventually led Kashmir to gain worldwide fame in carpet weaving, ranking second only to Iran.

Initially, Kashmiri carpets featured floral designs depicting scenes such as mosques, gardens, wild animals, and gliding fishes. The weaving process involved the weaver sitting on a low bench, using threads of various colors wound into balls hanging from a string. Following a written key or talim, the weaver tied a specified number of knots with woolen yarn of the corresponding color, using fingers instead of shuttle needles due to the coarser fabric. Each thread was cut after knotting, and the entire row was pressed down with an iron comb to ensure evenness, followed by clipping with shears to refine the surface of the carpet.

Kashmiri carpets achieved great intricacy, with some reaching up to 400 knots per square inch, occasionally incorporating silk and Pashmina wool to enhance delicate shadings in the designs. Techniques like the dense and pliable Persian weave were adopted to achieve both density and flexibility in the carpets. Patterns were often derived from illustrations of Oriental carpets published by institutions like the Imperial and Royal Austrian Commercial Museum, with special attention given to ensuring the color fastness of dyes used in the carpets. Thus, through the influence of Mir Saiyid Ali Hamadani and subsequent training abroad, Kashmir became synonymous with high-quality carpet weaving appreciated worldwide.

Since ancient times, the Kashmiris were familiar with the technique of hamams or hot baths, which were traditionally used individually. However, with the arrival of Mir Saiyid Ali Hamadani, this practice took on a new dimension. Mir Saiyid Ali Hamadani, also known as Shah-Hamadan, introduced the concept of community hamams, replacing the private family hamams that were prevalent.

Under his influence, it became customary to construct hamams alongside mosques to cater to the needs of Muslims who gathered for prayers. Additionally, community hamams were established in each khanqah, the Sufi cloisters dedicated to spiritual practices. The first community hamam was constructed at Khanqah-i-Maula in Srinagar, marking a significant shift towards communal bathing facilities that served both practical and communal purposes in Kashmiri society.

Wicker work in Kashmir received significant impetus from Mir Saiyid Ali Hamadani. In various villages, skilled artisans were already crafting essential items such as baskets for agricultural purposes and kitlas used in transporting apples and for general village tasks. However, it was under the influence of Mir Saiyid Ali Hamadani that this industry saw further development.

The establishment of the Amar Technical Institute marked a pivotal moment for wicker work in Kashmir. Here, efforts were made to innovate and expand the industry. Notably, experiments were conducted with English and French willow trees, which proved successful in Kashmir’s climate. This initiative led to the production of a wide array of exquisite items by Kashmiri artisans, including baskets, boxes, chairs, and the renowned kangaris (portable braziers).

The kanger, in particular, exemplifies the pinnacle of indigenous artistry in willow work, showcasing the craftsmanship and skill that Kashmiri artisans attained in this traditional industry.

Mir Saiyid Ali Hamadani played a pivotal role in introducing several arts and crafts to Kashmir, including book binding and hashiakari.

Under his direction, the art of book binding was introduced to Kashmir. Mir Saiyid Ali Hamadani assigned one of his disciples to train Kashmiris in leather book binding techniques, decorative covering, and embossing with gold and silver. This initiative aimed to embellish religious scriptures, sacred writings, and royal correspondence with intricate designs on embossed leather jackets.

Hashiakari, another art form introduced by Mir Saiyid Ali Hamadani, involves the decorative art of outlining leaves and documents. This technique was used extensively to adorn royal letters and other important documents, enhancing their aesthetic appeal.

Mir Saiyid Ali Hamadani’s contributions extended beyond craftsmanship to scholarly pursuits as well. He established the first manuscript library of Islamic books in Srinagar, Kashmir, which housed his personal collection alongside other significant works. A team of calligraphists worked under the supervision of the chief librarian, Syed Mohammad Qazim, to preserve and embellish these invaluable manuscripts.